My ’67 Mustang is imperfect, just the way I want it

When we drive our cars, they collect signs of that use—patina, in collector-car speak. The latest issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine, in which this article first appeared, explores the delight found in such imperfect cars. To get all this wonder sent to your home, sign up for the club at this link. To read about everything patina online, click here.

Once, on the way to school, I looked over at my father in the driver’s seat of our battered Suburban and asked him how he knew the past was real. He snorted a laugh, his eyes never leaving the road ahead, and said, “Because I have the scars.” It was the kind of answer that tumbles from a tired father’s mouth without a second thought, laden with heavier truths than he likely realized. Over the years, I’ve found it applies to more than busted knuckles. When it comes to cars, so much of our fascination is wrapped up in questions of authenticity and honesty. In proof of the past. Did Fangio sit here? Did Chapman put his hand on this panel? Does the machine have the scars that prove it suffered the slings of time and survived anyhow?

When I brought home my ’67 Mustang, I knew better than to believe it would ever be concours perfect. The original straight-six and three-speed automatic had long vanished. The cowl and floors had been carved out and replaced with cheap patch panels. There were at least eight layers of paint, some of it covering finger-thick Bondo. There was rust. There were dents and dings. The interior looked like someone had loaded a 12 gauge with self-tapping screws and pulled the trigger, but despite all of that, I loved it immediately.

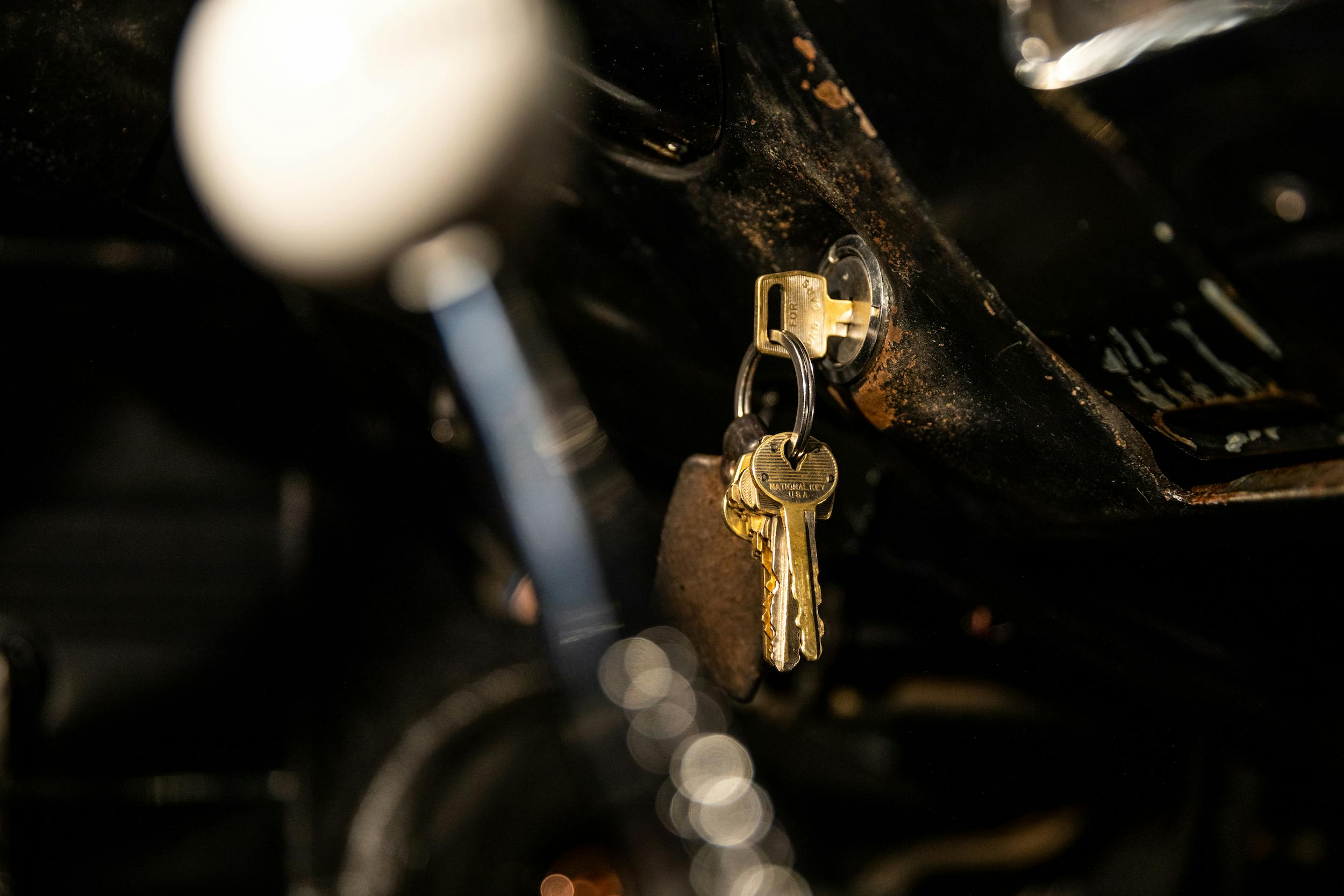

I didn’t want a $100,000 pony car with mirror-finish paint and panels straighter than anything that ever came out of Dearborn. I wanted something I could use. Something I could beat on with a hammer without batting an eye. A canvas for spray paint and cut springs that I could street-park with the windows down or fling at a curled mountain pass in the rain. I wanted a car that would remind the world why we all fell in love with these things to begin with, back when they weren’t investments or heirlooms. When they were simply the key that unlocked the brightest moments of our lives.

***

The idea was pretty simple: What would a former Trans-Am racer-turned-PI drive in 1974? Probably a hammered notch. The day after I got the car running, I unbolted the pony from the grille, pulled off the crooked fender emblems, and discarded the rocker trim, not bothering with the holes left behind. I tossed the dog dishes on a shelf in the shed and was left with a car that looked half a shade less grandmotherly than it had an hour earlier. Over the next few months, I threw a rash of speed parts at it, the only concession to modernity being a five-speed gearbox from a Fox body.

I raided Shelby’s cupboard for handling tricks, relocating control arms and cutting down coil springs with a hacksaw until the front hunkered low and right. A pair of reverse-eye leaf springs in the rear brought the back down, the car suddenly hunched over tall rubber and 15-inch Torq Thrusts sprayed gray. Magnesium 15s are a king’s ransom, but Rust-Oleum is still cheap as chips. I rolled the fenders, hammering them out until the body filler popped and the arches accommodated the Mustang’s new posture.

But this wasn’t just an aesthetic exercise. Sure, I’d spent hours scrolling through images of grainy SCCA events, the Terlingua cars hammering through corners. I’d watched and rewatched Bullitt. But I wasn’t building an Eleanor or some cosplay racer. My garage is half an hour from the Tail of the Dragon, U.S. Route 129. I needed this car to be capable of hounding a tourist in a new Corvette up and down the hollers between Tennessee and North Carolina. That meant Porterfield pads and a Borgeson steering conversion, gracing the car with a steering ratio quicker than a Miata. It meant an aggressive limited-slip differential and a 3.55 gear. An aluminum driveshaft and a 13-pound flywheel. Tri-Y headers breathing out barely muffled side-exit pipes. It meant giving the car all of the menace that the exterior promised.

Inside, I abandoned the factory gauges. I wanted the Stewart-Warner dials found in the Cobra, but modern reproductions don’t have a sterling reputation, so I settled on AutoMeter’s take on the same. And because this car pulls double duty as both back-road weapon and road-trip darling, it needed to have a decent stereo. I sent the previous owner’s gross single-DIN CD player to the dumpster, sourced a factory FoMoCo FM unit, and had its innards replaced with an Aurora Design Bluetooth system.

So much of modifying a car comes down to feel. Sometimes that’s the physical touch of the thing. Does the sideview mirror telegraph cold chrome or cheap plastic? Does the shifter notch into gear or flop over, lifeless? Other times, it’s what the components evoke inside you. The emotions they stir up in your chest in spite of yourself. When you’re behind the wheel, your field of view narrows to a handful of bits: the gauges, the wheel, a mirror or two. Get those wrong and it’ll feel like a poorly tuned guitar. Maybe that’s why it took me so long to find a steering wheel.

Having spent some time in a friend’s 289 Cobra, I knew I wanted a Moto-Lita, but a wood-rimmed hoop seemed out of place in the all-black cabin. Half a bottle of Willett and some eBay scrolling returned an immaculately hammered leather-wrapped tri-spoke. All black, with the cursive “Excalibur” barely visible just below the horn. Perfect.

***

Somewhere along the way, I accidentally built something I hadn’t had since I was 20 and sold my street/track Civic to buy our first family vehicle: my car. A machine built expressly around how I enjoy spending time. My wife, Beth, and I began taking it everywhere. Finding excuses to pile in and head off for the hills for impromptu overnights in Highlands or Asheville in North Carolina. Daring January snows and mid-June rainstorms. Arcing this ancient, hammered Mustang from one glorious apex to the next, the tired 302 shouting at the river and trees along the way. Or picking up our daughter from school, letting her slot that cue-ball shifter from one gear to the next from the passenger seat.

The shock is not how well the car drives or the wide smile of everyone I put behind the wheel. It’s how the world responds to this tattered old Mustang. It is universally loved. Regardless of age, gender, race, or creed, people smile at it. Have a kind word for it. The old guys who had one in high school see something more accurate than the Barrett-Jackson beauties that clog our Instagram feeds. The baristas see something more genuine than the usual parade of Teslas. In all my days of driving, I’ve never experienced anything like it. Sure, the Mustang is an American touchstone, a bit of the blood and bone of us, but it’s more than that. This car shows its faults and bruises, and despite its black hat stance and antisocial exhaust, that makes it approachable.

Makes it a thing worth loving. Maybe that’s what all of this chipping paint and dented metal offers us: a measure of honesty. Proof of the past. In a world so obsessed with the appearance of perfection and brighter futures, that’s more valuable than any concours trophy.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

perfect.

I have 1963 1/2 Galaxie 500 which I have owned for 37 years and it is also a driver with the scars that say been there and done that. I like restored cars but all that polishing gets old. I just hose off my old Galaxie when she gets dirty and hit the road.

I was actually disappointed when my sight-unseen purchase showed up; it was in immaculate condition with hardly a scratch. That means it sits in the garage most of the time and I spend more time waxing than driving. Fortunately it’s an old mercury, so not the kind of car to sling around turns. But I do wish I had a running older car with battle scars.

Love this car.

My 69 is similar in many respects, but this one is more purpose-built and executed –and gets used more than I can manage at this life stage.

Fantastic article Zach! Makes me wish I owned a classic Mustang!

Fantastic article. Zach knows how to share something he loves and reminds us why we love it too.

You are in touch with your inner self.

You are part hot rodder.

But you are wise, and you won’t regret your work. It’s horse of a different color.

Well done.

Never been a Mustang guy, but if I were, this would be the car I’d want to have!

Great article! I’ve had my 67 for 42 years. She looks and runs great but is definitely a 50 footer. I’ve told people many times over the years – “She’s no show pony, she works for a living. I drive her.” I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Nailed it, great explanation of how I feel about trailer queens and why I don’t have one.

pretty much describes how I feel about my ’66 Barracuda resto-mod – nailed it!

I have my Mustang set up very similar to this and I am very happy with it

So on the Popeyes, Spicy or regular?

Loved the story.

Oooo – spicy for me, please!

Ditto! Gotta have it fire.

Incredible. This is an old car that actually gets driven. I’ll bet the windshield wipers actually work. Cool story. You can actually drive this to Wal-Mart and not get an ulcer if someone parks next to you.

Great article. I relate very much to this one because my first car was a 289-powered ’67 Notchback. Bought it in ’74 when I turned sixteen. It started life as an automatic, but I swapped out the pedal box and put in a 3-speed from a parts car, then eventually installed a 4-speed. Went through a bunch of intakes and carbs, including a hi-rise twin four-barrel unit I borrowed for a weekend. It looked amazing with the hood off like that but ran like crap because I had nowhere near enough camshaft. This car is also the source of many wonderful memories. Like the time two friends and I drove to Key West from Tennessee Tech because we had about $25 bucks and a Shell gas card between us. Learned and lived much in that car.

This is amazing. Like everyone, I wanted a fastback for years, but the notch has grown on me.

Nice piece by a real motorhead. Thank you. Not a Mustang guy, but love the sentiments and upgrades. You can blame janitorial d’ nonelegances like Bauble Beach, which have nothing to do with the real European concours of the 1920s-early ’50s, where cars judged solely on line, form, presence, perhaps still some mud on their tires from being driven to the event the night before, with second-tiering, even trivializing, genuine buffs, whether they have less than pristine but well-fettled serious machines like Zach’s thunderbolt, or otherwise immaculate old road or sport cars occasionally driven for no good reason, like the automobiles they still are.

Thanks again.

It’s funny. In a former life I spent plenty of time in Monterey for car week, including on the lawn at Pebble. My favorite bits of that maelstrom were Dawn Patrol, where you actually get to see the machines drive onto the green, the Historics, where everyone’s out banging fenders and you can walk the paddock with cars that do more than strut on some grass, and the Preservation Class, which celebrates machines that have survived the years.

I’m glad shows like that exist, mostly because I’ll never be the one to mothball a car or go through the financial or mental nightmare of restoring something to beyond perfection.

That said, I’d still rather be out hounding the hollers.

Absolutely, and of course there are many beautiful, memorable cars at Pebble. It’s just that such shows have devolved to tournaments of credit line, witness two of the three recent Best of Show winners fielded by billionaires, the third a pauper with a mere half-billion-dollar net worth. Such “concours d’ elegances” have little in common with the genuine article in the 1920s through early ’50s, as explained above. Many of us are guilty of gilding the lily here and there, but Pebble veterans told me back in the late 1980s that a car whisked by time machine from 1930s showroom floor to Pebble would be hard-pressed to garner more than 85 points.

Phil Hill, whose Pierce-Arrow won Best of Show at 1955’s Pebble, the first vintage/Classic/old car to do so, and became partner in a Santa Monica restoration shop, Hill & Vaughn in the 1970s, later lamented seeing “more nice original cars forever ruined for the sake of a few more points at a concours.”

So Pebble, and the genuflecting before it, has gotten out of hand and second-tiered some wonderful, well fettled cars, as well as everyone else in this hobby.

Treasure your well-sorted, super ‘Stang.

I’ve got a ’63 Falcon Tudor real mid-year 260-Fordomatic. Former owner installed buckets and console. I’m collecting parts for converting to T-10. It’ll never be perfect, but it’ll be the driver I’ve always wanted… to MY specs.

Now… I’m looking at my restored Deuce Roadster trailer queen in the corner… what if I shuck the fenders… and finally bolt on the Eddie Meyer with dual 81s I’ve been saving…

Thanks for the inspiration!!!