How the Bugatti Royale was bred from an airplane and fathered a high-speed train

With the plethora of automotive offerings available today, it’s hard to stay on top of the world’s highest-performance cars as they jostle for status among hypercar royalty; but in the 1920s, the Bugatti Royale truly occupied a class of its own. Engine? Descended from that of an aircraft. Eight cylinders, arranged in a row, displacing 12.8 liters and boasting a nine-bearing crank. Power? 300 hp and a top speed of around 120 mph. To keep that elephant of an engine running smoothly took 23 liters of oil pumping through the dry sump system, plus an additional 43 liters of coolant oil.

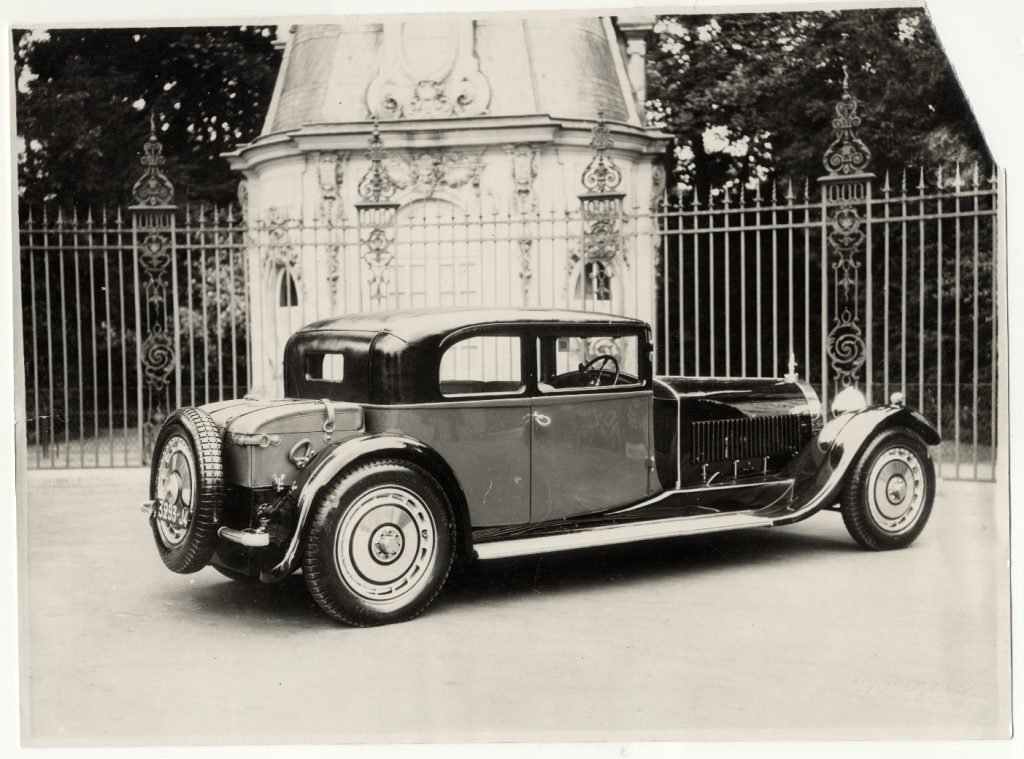

The physical presence of the car was impossible to ignore: that hulk of an engine powered a car as long as two ’66 Mini Coopers. Though the price depended on which coachbuilder you ordered your Royale body from, the Royale was three times as expensive as comparable motor cars and ten times that of any other Bugatti offering.

Head spinning yet?

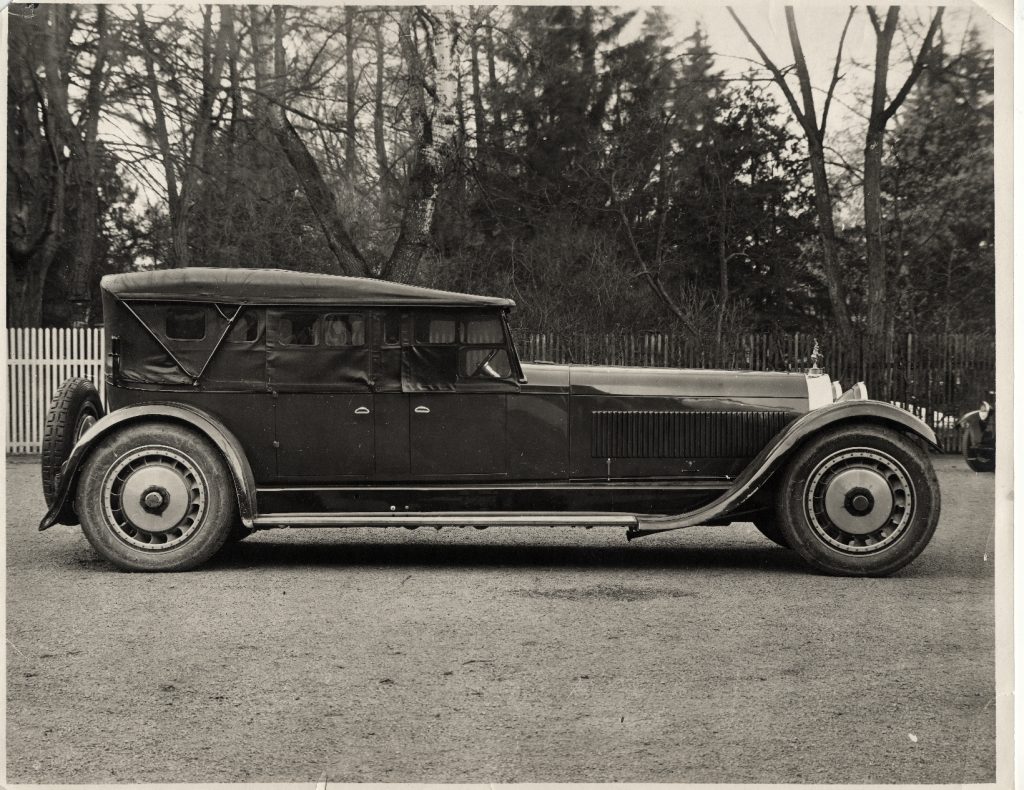

Though Bugatti built the first Royale prototype in 1926 (shown above), it didn’t sell the first example until 1932. To give you an idea of the kind of customer we’re dealing with here, the owner of that first Royale was Armand Esders. He was practically drenched in money. Esders was a Belgian-born industrialist who made a fortune in the clothing industry by taking his family draping business into the modern manufacturing age. He dabbled in three expensive hobbies—cars, planes, and boats—and didn’t order any of his cars with headlights, Royale included. Driving at night, clearly, was nothing to be feared. (A 65 meter yacht, staffed with a crew of 15 and equipped with a seaplane for an escape vessel? That was more his vibe.)

Three other Royales, each wearing different majestic sheetmetal, graced the garages of other exclusive clients. Bugatti would only make six models before 1933 and would sell only four, Esders’ included: a cabriolet, a Pullman limousine, a two-door limousine, and a folding-top travel limo. Naturally, Ettore Bugatti also drove a Royale, a specific body called the Coupé Napoleon that now resides in Mulhouse, France. (Bugatti informs us that Mrs. Bugatti “also preferred a Royale as a means of transportation.” I mean, if you have the option, take the Royale.) All six Royales exist today, with the final representative holding court at Bugatti’s headquarters in Molsheim.

After the Great Depression put a damper on the whole venture, Bugatti had dozens of monster straight-eights with no hope of putting them into automobiles. However, that wasn’t going to stop Ettore from putting his handiwork in the history books. Planes, cars … the one thing a Bugatti engine hadn’t powered yet was a train. Molsheim got to work developing a four-axle, multiple-unit rail train for an early state-owned French railway called État. In nine months Bugatti had switched gears to train manufacturing and rolled out a train comprised of three different models of WR (Wagon Rapide) railcars. The highest-trim and the articulated Triple railcars used four engines a piece; the lesser WL model had two. However, a ride in a WR railcar was no stately promenade in the country; during its first test runs, the train reached 172 km/hr, earning it the title of the first modern high-speed train, according to Bugatti. (Catch a glimpse of it in action here.) The trains remained in service from 1935–58. The railway conglomerate exists today as the SNCF, an acronym for Société nationale des chemins de fer français (French National Railway Company).

It’s a strange ending to the Royale story: an extravagant statement of luxury reserved for society’s elite but crippled by the depression that befell the world, an exclusive machine that found a second life as transportation for the many.