Without ’80s ska, the Motocompo might not have happened

The introduction of the battery-powered Honda Motocompacto scooter has gotten people talking about its spiritual, if not motive, predecessor, the gasoline-powered and oddly shaped Motocompo folding scooter, made from 1981 to 1983. If you know your history, you’re aware that the Motocompo was considered a bit of a failure when it was sold. However, it spawned a global cult following, with 40-year-old examples going for more than many new motorcycles cost. Not so surprising, then, that Honda looked to it for inspiration.

It is surprising, though, that the Motocompacto was not designed to stow inside the hatch of the motor company’s cute little EV, the Honda e. Why? Because the Motocompo was designed to fit inside the groundbreaking Honda City urban car, making the scooter a “trunk bike” (トランクバイク / トラバイ, toranku baiku / tora-bai), if you will. Actually, one could also say that the first-generation City was designed to fit the Motocompo, not the other way around.

The Motocompacto is not the first time Honda has made an electric version of the Motocompo. In 2011, at the Tokyo Auto Show, Honda showed the Motor Compo, a battery-powered foldable suitcase-scooter. Like its namesake, the Motor Compo could be stored inside a small urban car—in this case, the Micro Commuter concept—allowing the single-seat EV to share a battery with the scooter.

Honda’s idea to use a fuel-efficient small car to do most of a commute and then use an even more fuel-efficient companion scooter for last-mile transportation may actually date all the way back to 1965. A British Pathé newsreel from that year, featuring the little S600 coupe, shows that the two-door could accommodate both a set of golf clubs and, if you dismounted the handlebar, a Z series 49cc Honda “monkey” bike under the hatch.

It’s not clear whether the folks back at Honda headquarters in Japan were aware of that film, shot in the UK, though the use of the rare early Honda coupe and a Honda two-wheeler makes me think that the marque’s British distributor was involved, at the very least.

The actual story of how the little scooter came to be is a bit like the history of the Civic, another urban-branded Honda car. The Civic came about because a group of young engineers and designers persuaded Soichiro Honda, then close to retirement, that a new direction was needed if Honda were to be a credible automobile manufacturer.

Less than a decade after the Civic was introduced, after the 1973 oil embargo in the wake of the Yom Kippur War, fuel economy, always a factor in automotive sales, became a top priority. In April 1978, Honda’s research and development staff were given the commission to “produce the ultimate fuel-economy car for the 1980s,” according to the official history of the company.

By then, Japan had surpassed the United States in annual production of automobiles, but demand in the Japanese domestic market had softened. Honda was only selling about 300,000 units annually in its home market. Additionally, the success of Honda and other Japanese brands in the U.S. market led to voluntary import restraints, putting even greater pressure on Honda to build a successful new model for Japanese consumers.

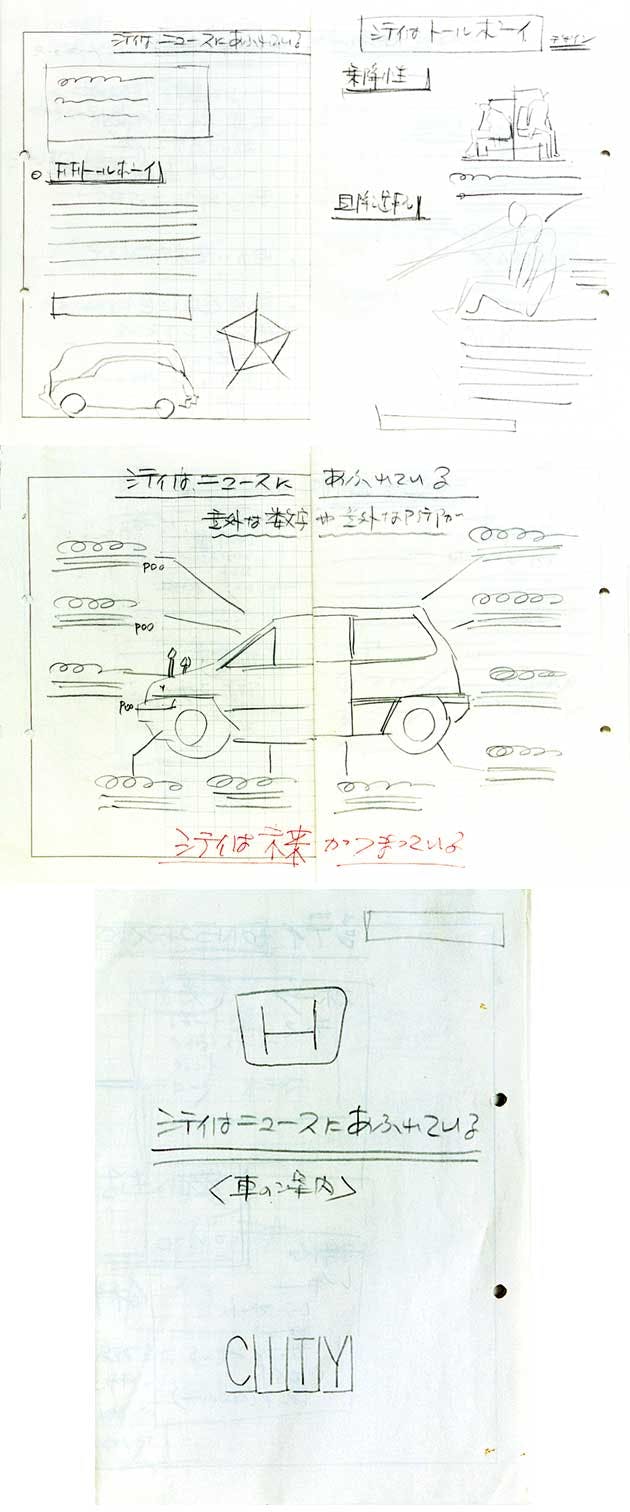

In 1980, Toru Arisawa headed the advertising section of the Sales & Promotion Division at Honda’s headquarters in Tokyo. Two young designers came to his office and entreated him to help them. Not one to turn down such a plea, Arisawa accompanied them to the modeling studio in the Wako R&D center. Inside the highly secure studio was a full-scale clay model of an unconventional car that the developers called SA-7. It left Arisawa awestruck and dumbfounded. The vehicle was tall for its size, but instead of being ungainly, it was cute. Arisawa insisted that the clay model be preserved.

The 1978 design brief for the new car had five bullet points.

- To create new demand beyond that of the existing market. Design a car that meets the public demand for resource and energy conservation, yet one that is especially aimed at young people as a fun, one-of-a-kind car.

- Deliver a car with excellent base performance to satisfy the users’ quest for the best. In addition, make sure it presents a new kind of lifestyle.

- Produce a car that young users —especially those who consider cars a daily necessity—will want to call their own.

- Design a car that fits Honda’s image as a creative car manufacturer.

- It must have a number of advanced features, and should have international appeal.

The design team knew what young users would want. Even after working on the car for two years, the average age of the design team was just 27 years. The designers felt strongly that they had met the objectives but they were worried that, because of their youth and lack of experience, Honda’s ranking executives would alter the design. They wanted Arisawa, Honda’s top marketer, to be their design’s advocate and keep its design pure.

“Blown away” by the design and believing it to be a return to Honda’s roots, he told them, “I won’t fail you. I’ll come up with something, ” and began to craft advertisements that reflected the unconventional nature of the car. There have been automobiles bearing the names of cities—the Chevy Malibu, Ferrari Berlinetta Boxer, and Pontiac Parisienne come to mind—but Arisawa took the bold step of naming the new urban car simply “City.”

In early 1981, when the R&D and marketing teams presented their work to Honda brass, Arisawa told them, “The SA-7 is the product of our young staffers, who have broken with established concepts. We will develop our advertising and promotional activities with presentations befitting such a concept. Please leave it to the young generation to take care of the SA-7.”

Unconventional seems to have been the watchword with the City teams. To appeal to young people, an attempt was made to create a City band, involving flying staff to New York City for auditions. Instead, however, the marketing team found out about an English ska band named Madness—most famous today for its hit “Our House” but then generally unknown in Japan—who had a bit of choreography they called the Centipede Dance. When the marketing team presented the idea to upper management, the response was, “Young man, tell me you are not serious!” The idea was rejected—repeatedly. But Arisawa persisted.

“Young people tell us they like it,” Arisawa told the executive in charge. “Old people say they don’t. But as long as we have 20 to 30 percent of the young with us, the goals of this car will be met. Please let us go ahead by using the youthful corporate image that Honda is known and respected for.”

With that, the executive relented, “All right, you’ve won my vote. Go ahead with the project. I will take the responsibility.”

Madness flew to Japan for two and a half days of filming and recording, including a scene doing the Centipede Dance to a catchy jingle that went “Honda, Honda, Honda, Honda.” The commercials were first previewed to dealers at a national meeting, and the reaction was positive. Once the commercial began to air, a popular nationally televised comedy show picked up the Centipede Dance and soon it, and “Honda, Honda, Honda, Honda,” became a national sensation.

When the City was officially presented to the public in November 1981, its most unconventional feature was revealed. The hatch opened to reveal that the storage compartment was designed to hold an optional, accompanying motor scooter they called Motocompo, that folded into a luggable size.

Folding scooters have been around for a while. The best known is the UK’s Welbike (sold in the U.S. by Indian as the Papoose), designed to be folded up into a tube and dropped by parachute to provide ground transportation to airborne infantry.

In the 1980s, traffic congestion was a serious problem in densely populated Japan. The City and Motocompo were designed together to address that issue. The idea was that you would drive the City would be driven to the, well, city limits, where you would park the car, unfold the Motocompo, and ride the scooter to your office. The sub-50cc engine displacement meant that you could operate it without a special motorcycle license.

As with the City, size and weight were key design factors. The Motocompo had to be light enough to be hoisted into the car and small enough to fit in it. The latter was addressed with hinges. The handlebars, seat, and pegs folded inwards, leaving the Motocompo in a roughly rectangular shape approximately 47 inches long, 22 inches high, and 10 inches wide. At 45 kg (99 pounds) the Motocompo didn’t affect the City’s fuel economy as much as a fully grown adult in the passenger seat would, but even with the City’s deeply plunging tailgate, designed specifically for the Motocompo’s access and storage (with straps, hooks, and even a custom cover), hefting it over the rear bumper was not an easy task.

The folding scooter was powered by a one-cylinder, 49cc two-stroke engine (with oil injection, not premix) used in other Honda scooters, rated at 2.5 hp and 2.75 lb-ft of torque. With a single gear ratio and an automatic clutch, it’s closer to a Briggs & Stratton–powered minibike than it is to a Vespa. Top speed is 18.6 mph (30 km/hr), but with just two and a half horses, that figure is highly dependent on the rider’s weight. It has all the equipment needed to make it street-legal, including indicators and a brake light. Those brakes, by the way, are drums front and rear. The Motocompo isn’t a hardtail; it does have a swingarm in back and a telescoping fork up front, but suspension travel is a bit limited. Kickstart only, likely because a starter and bigger battery would have made it even harder to get in and out of the City.

Fuel economy was outstanding—70 km/l, about 164 mpg—and at 80,000 yen, about $340 in 1981 currency (~$1150 today), the Motocompo seems to have been downright inexpensive. Perhaps that’s why Arisawa and his team actually thought the Motocompo, which was available both as an option on the City and as a standalone product, would outsell the car, 10,000 monthly units to 8000.

In reality, some months nearly twice as many Citys were sold, and 150,000 units were sold in the first two years. The Motocompo never sold more than 3000 units a month and less than 54,000 in total, despite all the clever promotion. Perhaps the Moto Compacto will do better than its combustion-powered ancestor. Like the Motocompo, Honda has priced the Moto Compacto very reasonably at $995.

Though the Motocompo went out of production in 1983, it was kept in the public view by You’re Under Arrest! a popular manga series that was published from 1986 to 1992 and adapted into a television show that ran for three years, three original video animation series, a full length animated film, and a live-action drama. In the series, police officers from the Metropolitan Police Department patrol the streets of Tokyo with their Honda City and Motocompo.

Of course, when something unusual becomes a cult item, rarity means increased value. If you think a Motocompo would make a cool paddock or car-show scooter for you, you can expect to pay somewhere in the mid-four figures, at least. At the 2020 Mecum motorcycle auction in Las Vegas, all three colors of the Motocompo were on the block, a white ’81, a yellow ’82, and a red ’84, that sold, respectively, for $6500, $11,000, and $5500.

(The ’82 and ’84 were both described as “brand new” so it’s not clear why one sold for twice as much as the other. The red ’84 was so original that it still had accessories in their original plastic bag. Perhaps the fact that the ’84 not only had never been ridden, but it also had never been started may have scared away a potential buyer who wanted to know that it actually ran.)

Mr. Motocompo, a division of Cycle Refinery in Lulling, Texas, also has a few in stock. They’re selling a set of all three colors of Motocompo, all “excellent restoration candidates” for $14,995.

All because of some imaginative young designers in the 1980s and a colleague who refused to give up on their idea.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I prefer the 80’s version. Funny to see the trio for sale not too far from me in Lulling.

Major Japanese corporations can be a bit stodgy.

It’s nice to see the mould broke on occasion.