Three 1960 drop-tops mark the fin-tastic last days of an American obsession

Today’s pop-culture, flash-montage mythology of the 1950s reduces the decade down to poodle skirts, hula hoops, doo-wop, and pastel-hued, postwar tranquility. American ideals of democracy and free enterprise seemed to trump all, and the standard of living was never higher as the new suburbs of our economic colossus brimmed with affluence and home appliances.

Yet, we were mired in self-doubt. “We have the most gadgets and the most gimmicks in our history, the biggest TVs and tailfins,” said a 42-year-old John F. Kennedy in announcing his candidacy for president in 1960. “But we also have the worst slums, the most crowded schools, and the greatest erosion of our national resources and our national will. It may be, for some, an age of material prosperity, but it is also an age of spiritual poverty.” At least some people agreed; he won that election, you may recall, and it was the start of one of the most tumultuous decades in American history.

All of which is to frame the scene into which our three feature cars were born. The 1960 Cadillac Series 62, the 1960 Chrysler 300F, and the 1960 Lincoln Continental Mark V arrived as latecomers to a party that was already winding down. Sensibility was in the air; Ford showrooms were just receiving deliveries of the trim and uncluttered Falcon, and the same Chevy dealer that could be-chrome you with a new Impala could also sell you the Euro-flavored rear-engine Corvair. And it’s almost inconceivable that the Lincoln pictured on these pages in all its finned, scalloped, bumper-bulleted baroqueness was replaced in 1961 by the so-called Kennedy Lincoln. Which didn’t look like it had come from an entirely different car company so much as from an entirely different planet. By the watershed year of 1960, America was at a turning point, and it had largely turned against tailfins.

You can’t say they didn’t depart on a high note. Part of the reasoning for gathering this trio from 1960 rather than from ’59, the year most people agree that tailfins reached their apogee, was pure, rank bias on our part. The final year of the tailfin—OK, like all fads they coasted on momentum for one or two more years—was also one of its best. The lines were clean and sleek, the chrome slathered on with, in many cases, more artistic restraint. If, as American Motors designer Dick Teague famously put it, it was “the golden age of gorp,” at least the gorp was ending on a grace note.

The stage on which we set our fin finale is Palm Springs, California, at the height of The Season. The desert retreat just beyond the mountains from greater Los Angeles has been a wintertime escape for the glittering and the gilded since Hollywood was young. However, the oasis named for its natural hot springs came into full frond during the postwar boom, when whole neighborhoods of midcentury villas were erected in the rigorously geometric, flat-plane, minimalist mold of architects such as Donald Wexler, John Lautner, William Krisel, and E. Stewart Williams. In the years since their heyday, what became known as “desert modernism” has become extremely vogue, and in its cooler winter months when the light is softer and 10,834-foot Mount San Jacinto looms over the city with a frosted crown, Palm Springs is a magnet for vintage style seekers of all persuasions. It seemed the perfect backdrop for our atomic-era finsters.

General Motors design chief Harley Earl generally gets the credit for inventing the tailfin. In fact, it was his underling, Frank Hershey, head of GM’s Special Car Design Studio, who took cues from the twin-tailed Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter plane and sculpted two gibbous protrusions for the haunches of the 1948 Cadillac. They were instantly controversial. Nicholas Dreystadt, the general manager of Cadillac at the time, is said to have hated them. His successor, John Gordon, wanted them reduced. Comedian Jack Benny quipped on his hugely popular radio show that they looked like “two salmon swimming upstream.”

Buyers had the last word, however, and despite a couple of recessions that temporarily dimmed auto sales in 1954 and 1958, they fell hard for fins. “People want beauty with a built-in feeling of motion,” said the Auguste Rodin of tailfins, Virgil M. Exner of Chrysler, who changed everything with his wider, lower, longer, and downsloping Forward Look of 1957. “Tailfins are a natural and contemporary symbol of motion, appearing on nature’s creatures and on aircraft, speedboats, racing cars, guided missiles, and rockets.” Accordingly, Chrysler’s sales went ballistic: The company increased its market share from 15 to 19 percent in 1957, mostly out of GM’s hide.

However, the mood shifted instantly on October 4 of that year, just a week after Chrysler debuted its 1958 models at a splashy gala at the Americana Hotel in Miami Beach. While Detroit’s color and trim staff were shaping fins and slapping on fake chrome rockets, Russian scientists had launched a real rocket. “In America,” a budding 17-year-old electrical engineer named Ronald Segall told a reporter as the world’s first man-made satellite beep-beeped from orbit, “it’s more rewarding for someone to produce a tailfin than a Sputnik.”

The nation was shamed. Suddenly, the soaring tailfin, that epochal touchstone of 1950s Americana, was Exhibit A in an indictment of our self-indulgent phoniness. Contrarians pushed back, and tailfins became the fulcrum of a vicious culture war. They were either “to American cars what embroidery is to Swiss cottage curtains and French cuffs are to men’s shirts … trimming to enhance the sale of a product,” as the conservative commentator Alice Widener reasoned, or, as the journalist John Keats remarked in his bestselling 1958 book, The Insolent Chariots, they were “illusory symbols of sex, speed, wealth, and power for day-dreaming nitwits to buy.”

“The tail-fin was horrid,” concluded the editors of Alabama’s Montgomery Advertiser in 1960, “but as a symbol of American decadence and ostentation, it infuriated the middle-class snobs, and that made it a satisfying national asset.” Or, in the parlance of our own times, tailfins owned the libs.

Certainly, Alex Lithgow’s red 1960 Cadillac Series 62 convertible is a national asset. It’s hard to imagine the extravagance of such a machine as it swishes along the Palm Springs byways amid today’s plasticized commuting corpuscles. However, at $5455 new, it wasn’t even half the price of Cadillac’s most expensive car that year, the $13,000 Eldorado Brougham. And at 18 feet, 9 inches, it wasn’t the longest model, either (the Seventy-Five sedan was over 20 feet). Lithgow, a commercial real-estate man in Northern California, came late to car collecting, falling for big Cads only a few years ago when he saw one parked in the garage of a house he was buying.

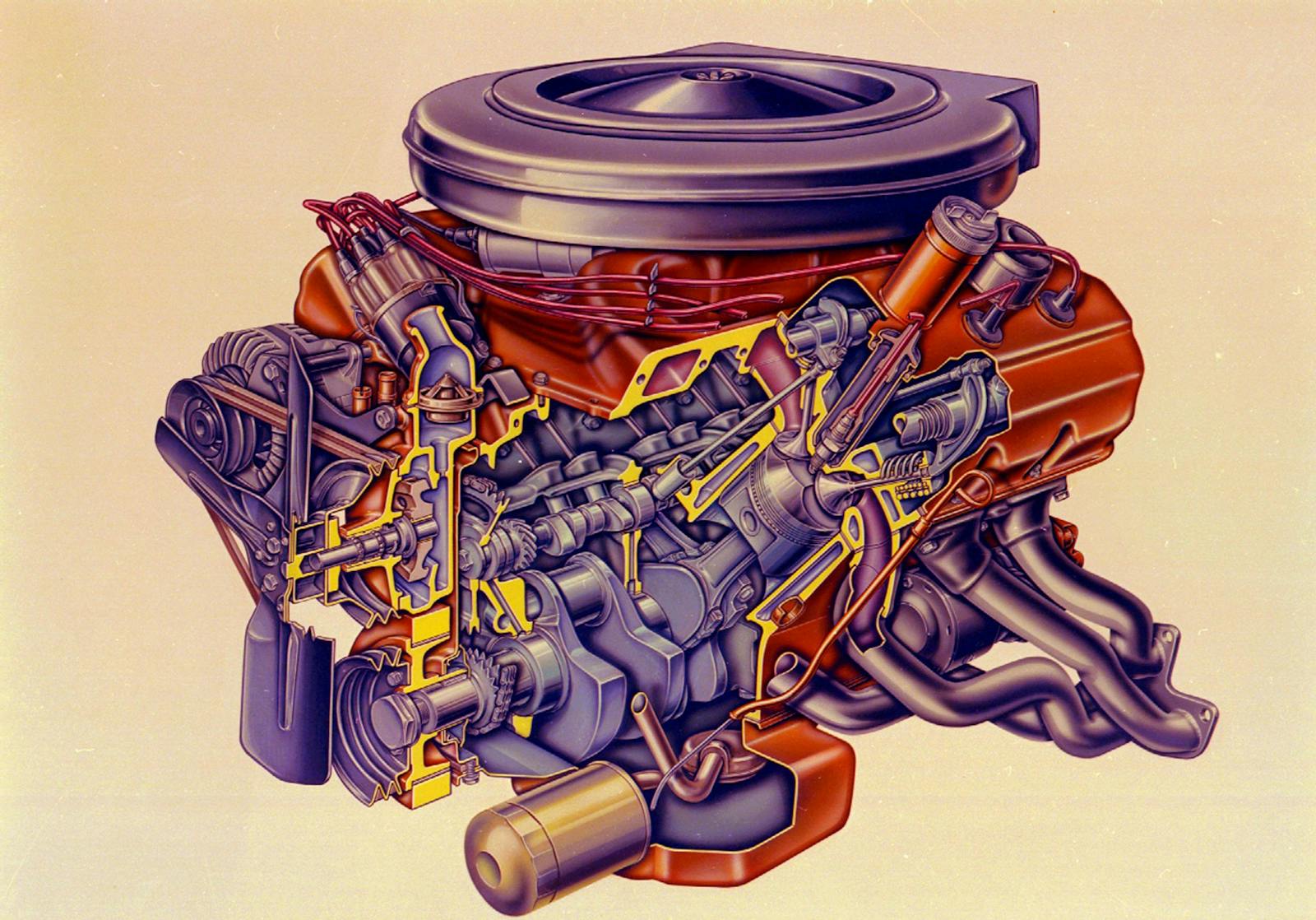

The Cadillac’s 390 V-8 rumbled sweetly as we purred through Deepwell Estates, a former horse and apricot ranch east of downtown Palm Springs that was redeveloped in 1952 into a neighborhood grid of midcentury masterpieces. Notable luminaries including Liberace (and his mom) owned houses here, as well as Liz Taylor, Carmen Miranda, Robert Livingston (the original Lone Ranger), Dragnet star Jack Webb, Jerry Lewis, and The Love Boat captain Gavin MacLeod. We paused for shots in front of the collection of white, perfectly rectilinear shoeboxes that formed the home of the late actor William Holden. His longtime neighbor, Cindy Quin, emerged from the house across the street to see what was going on.

Quin related how the 1953 Academy Award winner liked to water his flower beds in his sunglasses and swim trunks. One day a tourist bus pulled up and a lady in a big hat, not recognizing the celebrity, asked him to kindly step aside so that she could grab a snap of the house of the illustrious William Holden. The actor calmly obliged, setting down his hose and walking back into the house. “My mother and I died laughing,” said Quin. As we chatted, a line of private cars rolled up and stopped, their occupants also drive-through sightseers, listening via radio to a narrator in the lead car relate the history of the Holden house. The actor died in 1981, but the tours still come, mainly for the architecture.

Holden’s on-screen persona as the cynical everyman would clash somewhat with our blazing red Cadillac, but indeed the Series 62 seems the most rational of the trio. The layout of the contoured dash is by far the most conventional, the knob and switch placement rather lucid considering that most contemporary car designers seemed to be taking their cues from the movie Forbidden Planet. The only hint of flying-saucer gear in the Cad is the Guide-Matic Headlight Control, a small bullet on the dash that contains an optic sensor for automatically dimming the high beams when oncoming cars were detected. There’s also cruise control, a novel feature in 1960, along with power steering, power windows, power seats, and air conditioning.

Skimmed lower from the twin-bullet monsters of ’59, Cadillac’s 1960 fins actually debuted first on a special 99-car run of ’59 Eldorado Broughams whose bodies were handmade in Italy by Pininfarina (one later became the Ridler-winning hot rod CadMad). As on the Chrysler 300F, the Caddy’s fins come to bayonet points certain to fillet any unwitting bystander who is backed into. It was not without some justification that Ralph Nader had railed against such protrusions in his 1965 book, Unsafe at Any Speed. Still, a world that is perfectly safe would be unbearably boring.

Virgil Exner denied that his cars had any “Freudian implications,” though he conceded that fins are “definitely masculine” by nature. “They are masculine because they are directional,” he said, leaving posterity to interpret that comment. What did women want? “Ashtrays,” he said with a huff. “They want them in over 200 different locations. Tell them we’re trying.”

Exner suffered a heart attack in 1956, taking five months off to paint watercolors. He returned to a somewhat diminished role at Chrysler. However, the 1960 models, including the 300F, were already fleshed out, such are the lead times of car companies—then as today. The 300F thus qualifies as Exner’s déclaration finale, his last great statement on the subject of tailfins (the ’61’s fins were barely changed). And yow, it was a lulu. Even longer and taller than the 300E’s, the F’s fins sprout from the car’s torso mid-door and knife up and out, spreading into glorious steel sails to catch and direct the rushing wind. Or something—even Exner eventually admitted that their aerodynamic utility was speculative.

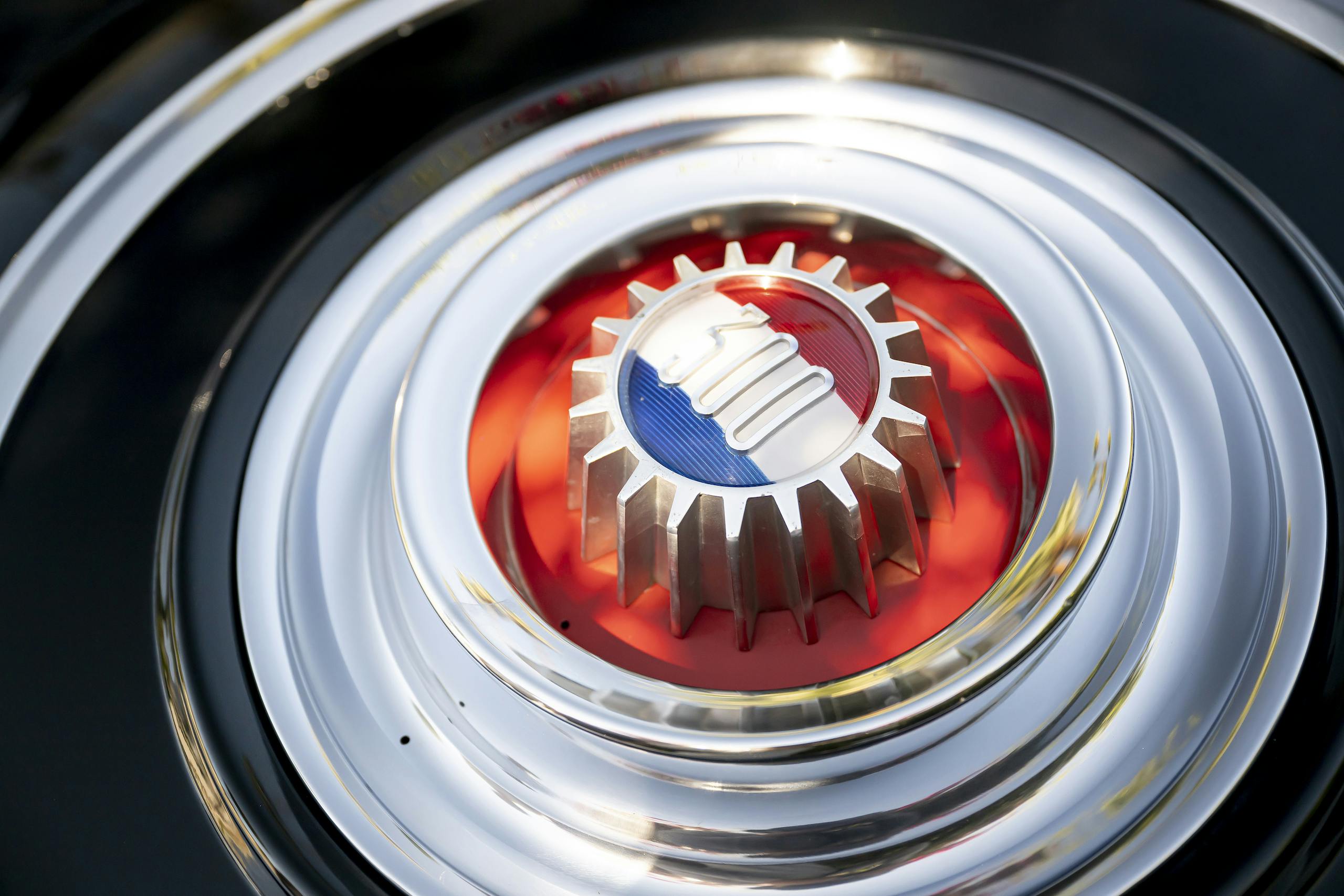

There’s no doubt that you’re driving Chrysler’s sportiest and most expensive model for 1960, since the number 300 is scrawled on the car in about 300 places. Of course, it’s featured prominently in the tri-color emblems on the side spears, but it’s also placarded on the steering wheel, the doors, a big gear-like badge between the separate rear seats, an insert on the faux spare tire (or atom-smasher?) housing gracing the trunk, all four hubcaps, the grille, and probably all eight piston crowns in the cross-ram 413. If anybody asks you what you’re driving, you’re forgiven for bursting into tears.

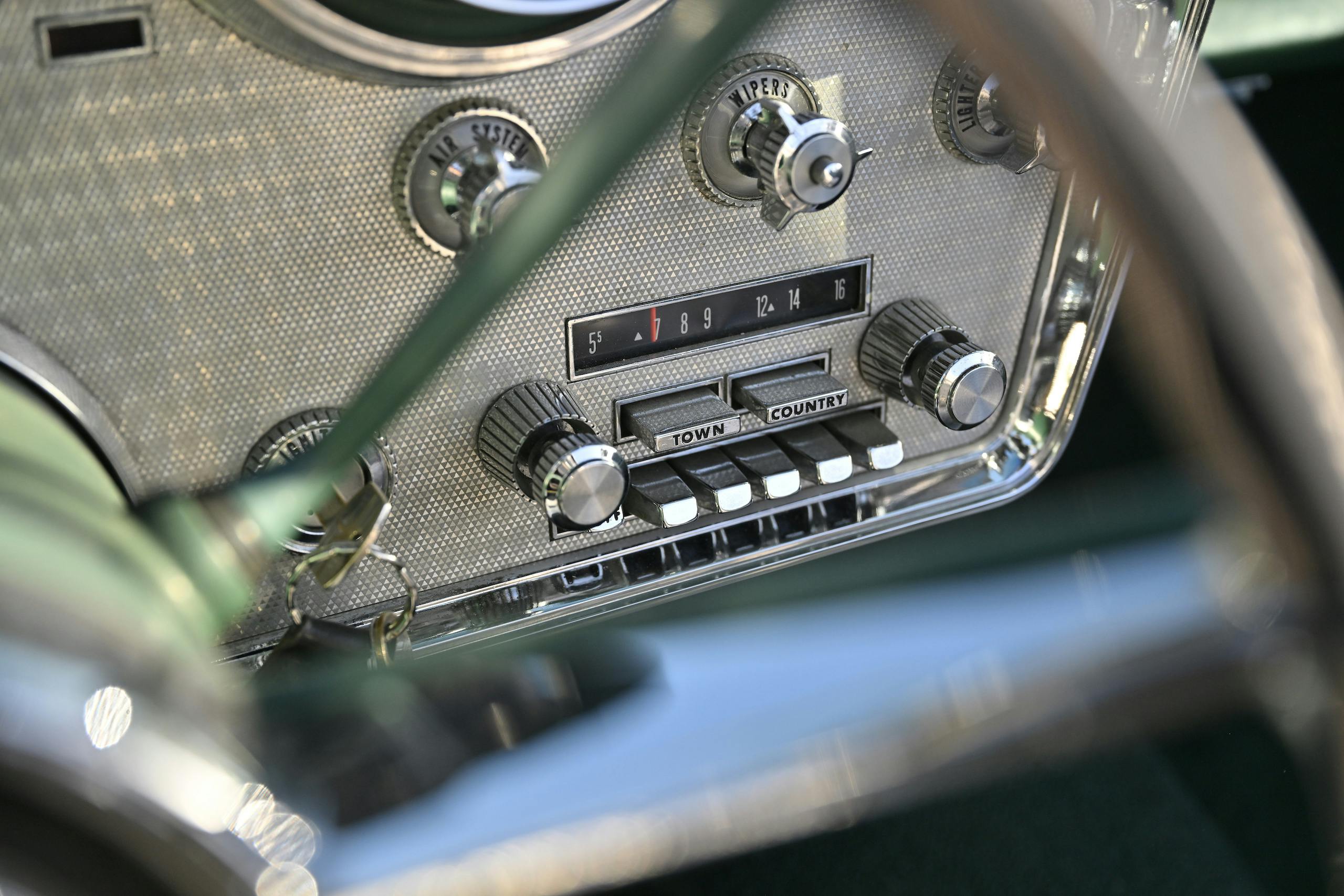

Besides the fins, the badges, and the early adoption of unibody construction, Chrysler’s most glorious bit of design kitsch for 1960 was the AstraDome Control Center. A plastic bubble containing layered arcs of three-dimensional gauges is the electroluminescent centerpiece of a button- and knob-a-palooza that made drivers in 1960 feel like they were navigating the stars rather than the new Cross Bronx Expressway. The five push buttons controlling the TorqueFlite transmission, an idea that first saw light in 1956 Chrysler brands, were still considered space-age even by 1960. Sure, the world had problems, but Chrysler was pinning its sales to a sort of trippy astrophysical optimism that one day we would all have our own rocket ships.

Basically a loaded New Yorker with more horsepower and some extra trimmings, including power swivel-out seats, this 300F ($5841 new) belongs to Paul Forgette, a Mopar collector from the Los Angeles area with several Forward Look cars in his stable. The glossy black 300, one of just 248 convertibles made that year, was right at home burbling up to the pull-through portico behind the former Coachella Valley Savings and Loan, built in 1961 and now a Palm Springs branch of Chase Bank.

The E. Stewart Williams–designed structure is on the National Register of Historic Places because it oozes midcentury Jetsons chic, with its high, flat, and deeply overhanging roof buttressed by inverted parabolic columns. What a stark contrast it was to the many Parthenon knockoffs then dotting cities across America, blueprinted to rigid neoclassical convention with Greek columns and frilly detailing. A deposit in Williams’s futuristic bank was a deposit in the world of tomorrow.

No wonder cars were changing; architecture as much as America was moving at supersonic speed, and modernism was everywhere. Three landmarks of transportation design—the saucer-like Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport, the swooping terminal at Dulles Airport, the neo-futurist domes of the TWA Flight Center at John F. Kennedy Airport—all opened between 1961 and ’62. Even the places where cars were designed and engineered were getting with the program. General Motors had opened its new Technical Center in Warren, Michigan, only in 1956. Designed by Eero Saarinen, who also did the Dulles and JFK terminals, the campus was a midcentury tour de force with floor-to-ceiling glass, levitating stairways, floating cubes, polished-metal guy wiring, and shallow reflecting ponds.

Key elements of midcentury architecture are authenticity and simplicity, not two words commonly associated with 1950s cars. Fins, bullets, strakes, and fake rockets met their doom in a burgeoning crusade for forms that were geometric, simple, modern, and clean. But before it all ended, Ford’s Lincoln luxury division wanted one last word.

Buttoned-down, family-run Ford didn’t embrace the tailfin with the exuberance of its competitors, the Dearborn fins never amounting to much more than relative nubs or suggestive creases, even at the fad’s zenith in 1959. Henry Ford had been in the ground just over a decade, and no doubt his wizened puritanical specter still loomed over the Albert Kahn–designed Ford Rotunda. The 1930s art deco building burned to its destruction in 1962, perhaps finally releasing that oppressive spirit to the great beyond—the Mustang appeared two years later.

It should be noted that Lincoln took more risks, especially with the ’57 Capri and Premier, which were about as finny as any Ford division ever got. The cars that followed, especially the crème de la chrome Continental, were a double-barrel shotgun blast of late-1950s design motifs—fins, glitter, starship controls—into what was still a fairly upright and imperious package that defied the longer-lower-wider trends at the competition.

The Continental Mark V pictured here swanning through its element in Palm Springs was our most expensive car new ($7056). It is also the heaviest, at nearly 6000 pounds. The 131-inch wheelbase is the longest, as is the 227-inch overall length, and the car is over 6.5 feet wide. Lincoln produced just a little more than 2000 Mark V convertibles, with an enormously complex roof and motorized window-within-a-window rear pane that let the driver drop either the rear glass or the entire roof at the push of buttons. The works disappeared under a self-retracting tonneau cover.

When this robotic spaghetti splicer has problems, which is not infrequently, David Freedman—an L.A. television producer who has owned the car for more than 25 years—applies a knowing touch to the various switches, joints, and boughs to get it to move. Luckily for us, the roof had recently undergone a restoration at a shop in Hollywood, and the car’s mighty spread of canvas folded away with only mild groans from the ancient clockworks hidden beneath.

Unlike the racy Chrysler and the slinky Cadillac, the Lincoln feels the most like a mobile throne. The flat, button-tufted bench affords you a commanding view, especially of the imposing dash with its tapered jet nacelles housing the gauges and its many appliqués of metalized textures. The steering wheel hub alone is fascinating: The trademark gold Lincoln star seems to float above a disco ball surface composed of tiny, interlocked triangles. It looks like something a semiconductor fab made last week in South Korea, not some trinket of interior jazz from 60 years ago.

Until a sudden brake-lining failure slowed the car’s pace, the Lincoln performed for us like it was new, the big 430 purring as if it rolled out of the plant minutes before. Despite its bulk, it wasn’t difficult to wheel through modern traffic, just as the Chrysler and Cadillac also seemed perfectly at home crisscrossing the wide boulevards of Palm Springs, making their occupants feel like a million bucks. Anyone who has driven a car from this era knows what they drive like: floating suspensions, leisurely acceleration, and fingertip steering effort.

Ad copywriters loved to weave word-carpets in Life and Look about the “command feel” of a “highway-tuned suspension.” However, even if the Chrysler’s 375-hp 413 was indeed a preview of the horsepower wars to come, Detroit was still focused on velvet-wrapped luxury as the sole determinant of a car’s worth. These days, the ideal way to enjoy a fin car is to don your best trilby, throw an arm over the seatback, and cruise like you own the joint.

And that’s what these cars do—indeed, did back then for the people who bought them. If the world of 1960 was speeding up and shrinking rapidly, these cars made you feel like you still owned it. John Keats railed that the automobiles of the era were not “reliable machines for reasonable men to use,” but instead resembled “vast, neon-lit pinball machines with the chromium schmaltz.” Ultimately, though, the schmaltz lost, and “reasonable machines” went on to rule the earth. Meaning today’s newest five-door, all-wheel-drive, multi-activity, active-safety hybrid crossover is barely distinguishable from last year’s. Yay for progress.

Maybe it’s because we had spent a couple of days driving the perfect cars in the perfect setting enjoying fairly perfect Southern California weather, but if forced to pick a side, reliable machines for reasonable people or tailfinned schmaltz for daydreaming nitwits, we stand proudly with the dreamers who wanted in their cars a taste of an optimistic future.

***

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.