Revisiting Walter Chrysler’s dreams with an unrestored 1931 Imperial

Once upon a time, in the late 1950s, this 1931 Chrysler Imperial sat forlorn and for sale, with a broken piston, on the forecourt of a Long Island gas station. It’s a sad but familiar tale: As luxury cars age, they often fall victim to owners with champagne tastes and Two-Buck Chuck budgets. In the decade of the tailfin, many Depression-era beauties that had survived WWII’s scrap drives reached the crusher. Those cars that survived were often restored in the 1960s, destined for the world’s most prestigious concours, such as Pebble Beach or Amelia Island. Miraculously, that CG-series Imperial, now owned by Greg Nowak, met neither fate.

Though Nowak lovingly made the Imperial roadworthy again in 2009 after a six-decade slumber, it has never been restored: He prefers its scars, oxidation, and worn furnishings. The car is rarer still because it retains its factory-issue Close Coupled Sedan body, and is not a later, phony phaeton or roadster replica. There aren’t many classic cars quite like it today.

Pebble’s judges might scoff at this Imperial’s visible age, but its imperfections make the car relatable to ordinary enthusiasts in ways that a 100-point concours winner is not. The Imperial feels like living history, a window into a brief period when Chrysler’s horizons and those of other luxury car builders were seemingly limitless. It also witnesses to the sort of lives these cars led after that heyday.

Glitter and gloom

It was May of 1930 when Manhattan’s glittering Chrysler Building opened, then the world’s tallest structure. Two months later, the wraps came off the equally glamorous new Chrysler Eights, so named after the number of cylinders in their engines: the mid-range CD-Series and the huge CG Imperial. At the time, Walter Chrysler and his company seemed invincible. In nine years, the ex-railroad engineer and Buick exec had turned tiny, ailing Maxwell-Chalmers into America’s third-largest automaker. In 1928, the company bought Dodge and rolled out the DeSoto and Plymouth brands, and Time magazine made Walter P. its Man of the Year.

Of course, all was not well. “Early in 1929, it had seemed to me that I could feel the winds of disaster blowing,” Chrysler later wrote in Life of An American Workman. While nobody knew how deep the depression would go in the summer of 1930, car sales tanked. They fell 40 percent by year-end, further weakened by a cascade of bank failures that autumn. The new Imperial was a car made for a world that, for most people, no longer existed.

At $2745 to start, even the cheapest CG cost twice what an American family made in a year. However, the CG handily outsold its 1929–30 predecessor, the 80L-Series Imperial. There was no time to enjoy that victory—“We had to cut salaries, reduce operations, retrench in almost every way,” Chrysler later wrote—but the CG’s sales were probably heartening. It was a car Walter P. had long wanted to build.

All hail the Imperial Eight

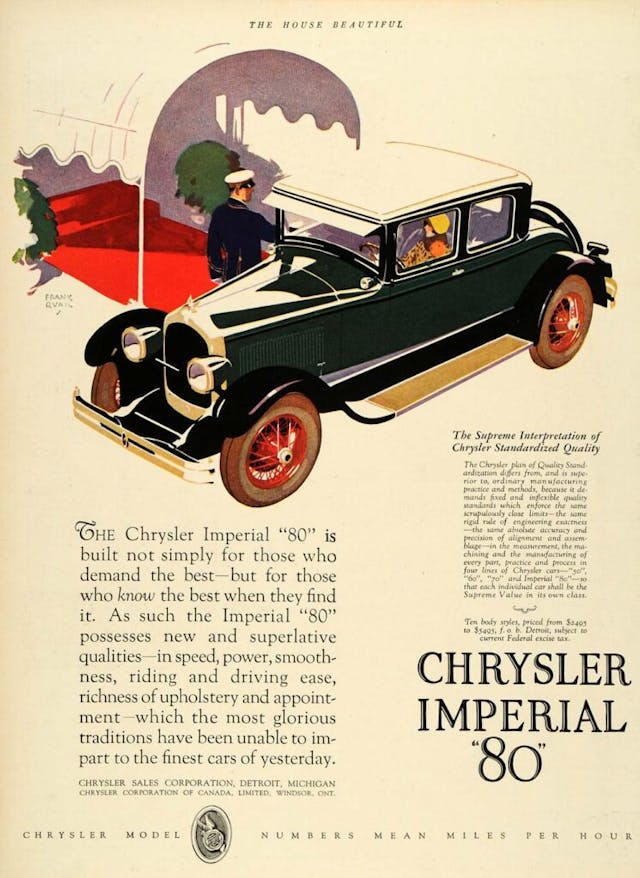

The first Imperial, 1926’s six-cylinder 80 Series, was essentially a scaled-up version of the 1924 70-Series Chrysler Six. The 80 wasn’t the Cadillac killer the founder envisioned, but it was far from bad.

Designed by Chrysler’s “Three Musketeers” of engineering—Carl Breer, Fred Zeder, and Owen Skelton—with Vauxhall-like lines (the British firm actually threatened legal action) probably done by body engineer Oliver Clark, the 80 Series was handsome, durable, and fast. As its name suggested, it was a true 80-mph vehicle, with advanced features like hydraulic brakes. Despite decent sales and a selection of attractive semi-custom bodies, the car was clearly a cousin to the lesser Chryslers, and its engineering would soon fall out of fashion: By 1928 big six-cylinder engines had lost the luxury race, which had been led by Packard, to straight-eights.

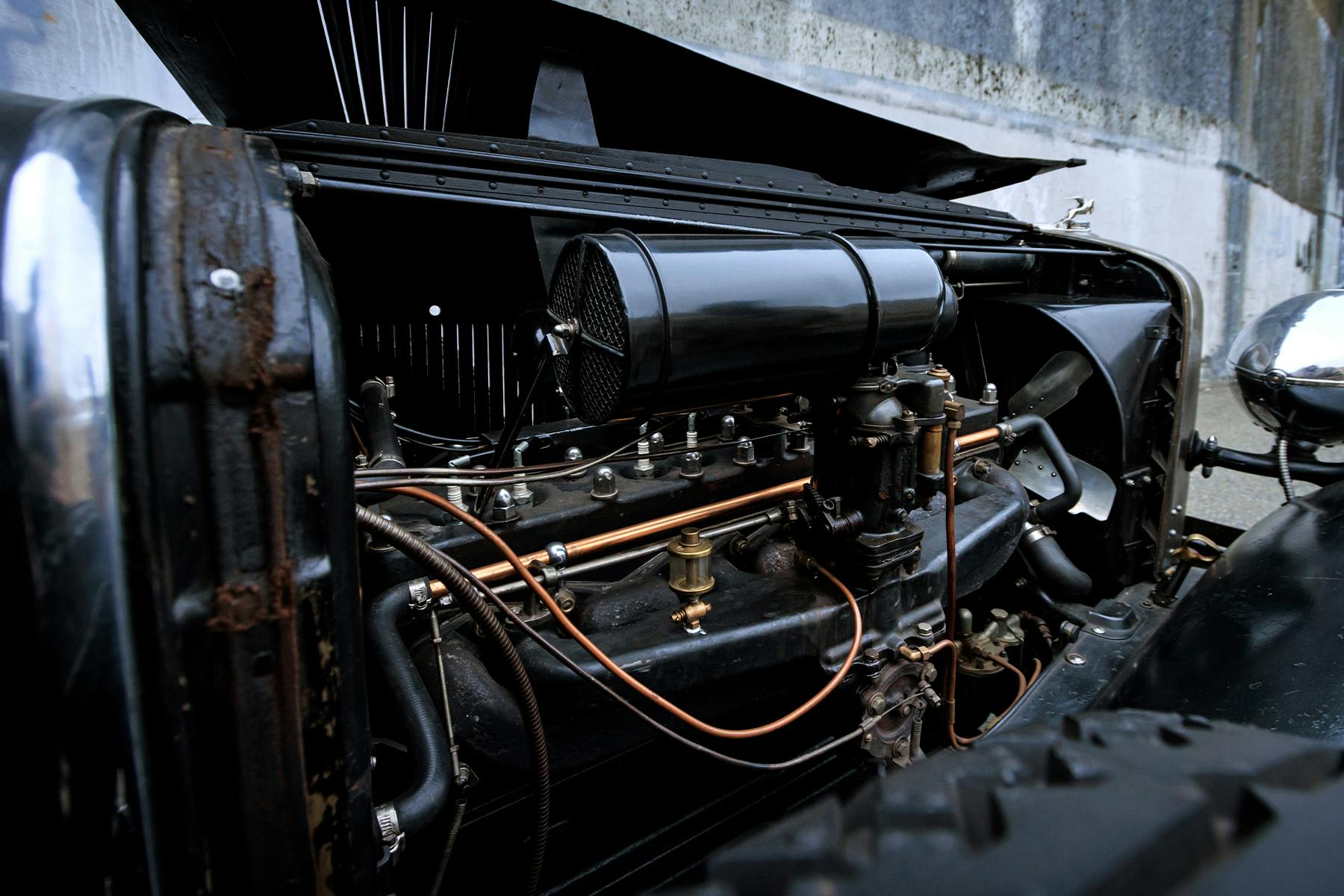

Consumers liked straight-eights because they signified prestige, and also because of the design’s smooth power delivery. In America, straight-eights tended to be torquey, long-stroke affairs, and this personality reduced the need for frequent shifts—a real luxury in the low-octane, pre-synchromesh world of the 1920s. Chrysler and his Musketeers preferred six-cylinder engines but could see the writing on the wall, and in 1927 Zeder began working on new straight-eights. DeSoto and Dodge got their versions first, a decision that helped the bottom line in 1930. Chrysler Eights followed right behind.

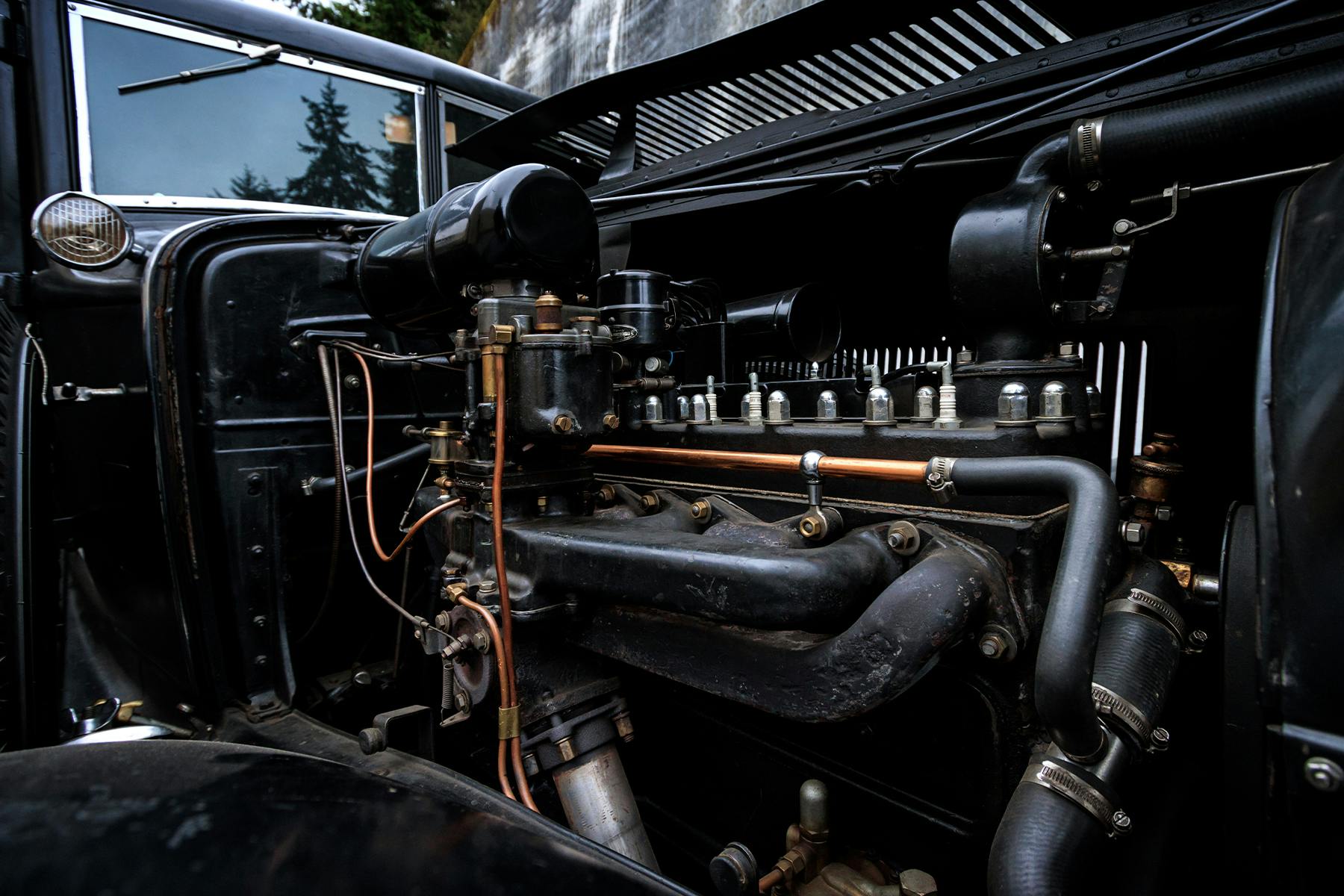

The bigger version of the engine would be the CG’s 385-cubic-inch job, with 125 horsepower, or 135 with an optional high-compression head. The engine’s muscularity allowed Chrysler to build a much larger Imperial. The Musketeers designed a whole new chassis on a 145-inch wheelbase, five inches longer than a 1929 Cadillac and nine inches longer than the 80L.

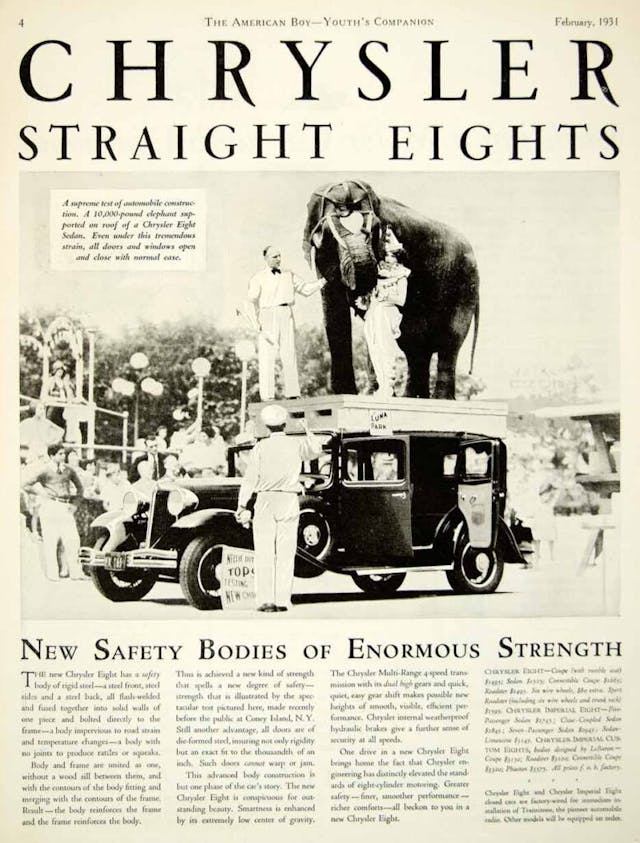

The strength of the frame was later demonstrated on Coney Island when a five-ton elephant stood on the car—and it did not collapse. The new engines and cars went through 200,000 miles of testing all over the country, led by ex-Duesenberg engineer Allen “Tobe” Couture, a long-time friend of the Musketeers. When passersby asked what the cars were, Couture would only say “Eagle Specials,” and tell the drivers to quickly move on.

All this testing, and the Musketeers’ knack for producing a good-handling, durable car, would pay off: CG-Series Imperials, nearly stock, competed at the 24 Hours of Le Mans and Spa in 1931. Though a broken radiator ended the Le Mans run, the Imperial finished third overall at Spa, winning its class and trailing only a Mercedes SSK and an Alfa 6C 1750 GS.

Art & Colour, take two

In the summer of 1929, as Chrysler was casting around for visuals for the new car, the Al Leamy–designed Cord L-29 burst into the public consciousness like a lightning bolt. Long, low, and amazingly rakish, the Cord sent Chryslers engineers rushing to one of Highland Park’s tiniest offices: Art & Colour. (Walter Chrysler had lifted the name, and the idea, from GM a year earlier.)

Chrysler’s A&C section was quite different from Harley Earl’s. It had very talented designers, including Henry King, Tom Martin, and future Ford and Kaiser staffers Buzz Grissinger and Herb Weissinger. All of them, however, were accustomed to playing second fiddle to engineering. Decades later, Martin told automotive historian Mike Lamm that Breer, Zeder, Skelton, and Mr. Chrysler would make decisions right there in the room with them. “It was quite a nice thing,” Martin said of their feedback, “because we got it first-hand.”

The feedback they got in the summer of 1929 was to shamelessly adapt the L-29’s looks for Chrysler’s new Eights, a brief they were happy to have. Weissinger, only 21 when he was hired, took the lead and sketched dozens of side profiles and front ends. Some incorporated the L-29’s shield for its front-drive mechanicals, and Weissinger even asked Zeder if either front-drive or a rear-engine layout would be possible; he wanted to reduce the height of the car. Zeder said no, though he did allow the engineers to lower the chassis a little.

In the end, the CG would be 67.25 inches tall to the Cord’s 61—4.75 inches lower than the 80L Imperial. Though the huge wheelbase gave the CG the proportions of a Cord, Weissinger’s design diverged from the L-29 in many areas. The bodies were designed by coachbuilders like LeBaron, Dietrich, and Locke as well as house body-supplier Briggs. Even more specialized bodies from Waterhouse and others could be had for a price.

The Close Coupled Sedan, the most popular body, came from Briggs, who made 1195 of them. Though the vehicle was stately, Chrysler’s catalogs proclaimed that it was “for the man or woman who enjoys the privilege of taking the wheel, preferring the thrill of driving to being driven.” Inside, in addition to a wealth of soft Bedford cord, buyers found many conveniences new in the 1930s. The front seats and steering column were adjustable, and there were running-board lights that lit when the door opened.

Movie stars to parts cars

The CG series hit dealers in mid-July of 1930, and it’s entirely possible that Walter Chrysler himself shuffled between the Simons-Stewart Motors’ Broadway showroom and his private dining room atop the Chrysler Building’s Cloud Club event space. The company sold 3228 CGs before the model gave way to the revised CL and short-wheelbase CH in mid-1931. Despite the souring economy, sales of the CG were 29 percent higher than those of the 80L during its whole run from 1929 to 1930.

Many Imperial owners were doctors and lawyers. The car’s undeniable style also attracted celebrities, including Anita Page, Myrna Loy, and former New York governor Al Smith. Ironically, in 1931, Smith ran the company that built and managed the Empire State Building, which soon stole the title of world’s tallest structure from the Chrysler Building. Walter Chrysler also bought a CG-Series LeBaron town car for his wife, Della.

What of the Imperial you see here? “The story,” says Nowak, its current owner, “is that the car was bought new by a guy named John Nonnenbacher, who was the manager for Jose Greco [a famous flamenco dancer]. Unfortunately, I don’t have documentation,” Nowak says. Greco, who made his U.S. debut in New York in 1937, probably didn’t ride in the car, but John F. Nonnenbacher Jr., an established New York City talent agent, was Greco’s manager for decades, until he died in 1970.

The story of this Imperial’s early years came from the late historian and car-collector Sam Berliner III, who found and bought the car at a Gulf gas station on Commack Road.

After Nowak bought the Imperial, he got in contact with Berliner, who related that he had once followed Nonnenbacher, who was driving a 1937 Cadillac, back to the agent’s home, hoping to inquire about the Caddy. It was then that he discovered the Imperial in Nonnenbacher’s garage. Some years later, according to Berliner, the Imperial turned up for sale at the station, running but in rough shape. Berliner, recognizing the car, bought it. He had to tow the car back to his house with a Jeep, supposedly because, according to Nowak, “a bunch of kids who worked at the gas station decided to take it for a joyride and blew one of the pistons.”

At the time the old-car hobby, and publications like The Horseless Carriage Gazette, focused on cars built before WWI. There were few clubs, no Cars & Parts magazines, and no organized way to find junkyard wrecks. Berliner tried fitting a Chrysler “Majestic Eight” marine engine only to find that it rotated backward. He eventually gave up and sold the Imperial to another Long Island collector, Scott Collins. Meant to be a parts donor for Collins’ Waterhouse convertible, the Close Coupled Sedan then sat for five decades.

Back to life

Collins eventually sold the Imperial to another collector in the mid-2000s. In 2008 that owner sold it to Nowak, who was drawn to the car because of its Cord-like style. “I particularly like the close-coupled body, because the trunk is better integrated than the other styles, but also, I could never afford one of the open ones.”

Amazingly, the owner of the Waterhouse seems never to have used any of the Sedan’s parts. “All of the little fiddley things, like the locks for the side-mount spares and the air filter box, it was all still there,” Nowak says. “That it was complete was a big deal, because good luck getting parts for these [cars].” Although he has owned a 1950 Imperial, “Chrysler’s last straight-eight,” the ’31 is a whole different animal.

Though complete, the Imperial hadn’t run since the rumored joyride incident. It still had a broken piston. Original replacements cost the earth, and Nowak, a house painter by trade, couldn’t afford them. “I’m not Jay Leno,” he jokes, “but I am resourceful.”

Not long after buying the car, Nowak saw a listing for a boring bar in the Chrysler club magazine. “It belonged to a mechanic for Kenmore Air, a float plane company that flies 1940s-era DeHavillands. He said it had been on his desk for years, but the last car it was used on was a Dodge straight eight.” Nowak bored out the cylinder, installed a sleeve, and fit a new .030-over Elko-König piston. He then rebuilt the top end of the engine with newly made valves and guides.

“There are nine main bearings, but everything seemed fine down below, and the gearbox was in great shape too.” After about 10 months of tinkering, replacing gaskets, and completely re-doing the brake system, the car was ready to go.

Just as Zeder planned, the big eight-cylinder is whisper-quiet and torquey. “It has a five-inch stroke, so you don’t have to shift that much, and first gear is a crawler anyway.” Although Nowak usually drives the Imperial on local streets, he has gone on faster routes as well. “Once, after a photo op in Columbia City, it was starting to rain and I wanted to get home, so I took the old Seattle viaduct home and got it up to 75. At that speed it’s very responsive, and it certainly gets other drivers’ attention!”

Nowak has absolutely no plans to restore or paint his Chrysler. “People might say, ‘Oh Greg, it needs paint,’ but it has paint. Original paint. You can’t replicate that.” The comments and questions he gets because of its condition are also part of the appeal. “It draws a crowd everywhere it goes, and some old timers even get dewy-eyed getting to experience it. Why change it?”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Beautiful car and a great story!

Exactly right!

I love these stories of finding these cars. I know he can not afford to restore it but I hope he can preserve it properly.

Very interesting story. I did not know about this car. Looks great to me.

Why restore it? I’m for leaving just the way it is. Let it proudly show it’s aged.

Great article, thanks ! To my eye, about the only improvement to the car’s styling would be if they’d laid the windshield back to the same angle as the grille. And I agree, it should not be restored, but rather preserved.

I once bought a 65 four door Chevy II from the family of a little old lady going into a retirement home. I was the 2nd owner as she still had her original bill of sale in the glove box. She even had a small card taped to the inside of the glove box door with safe driving instructions. It had the smallest 6 cylinder, a 2 speed power glide tranny and ran like a top. Totally unrestored and I bought it for $300. It’s one of the ones I wish I kept.

I found my 1940 Buick convertible in a gas station in 1959. It caught my eye and I stopped to see. The top was shot, the car was dirty with stickers on the bumpers, surface rust on the instrument panel, however under all that was the original black lacquer. The owner asked if I wanted to buy it. He said the junk yard would give him 15.00. I could have it for 25.00. I only had 5.00, so I went home and borrowed 20.00 from dad not telling him what for. I came home and showed him the car. He just loved it and had to test drive it.

I still have it and have authentically restored only as necessary.

Alex, a topflight story on a deserving barouche and owner. Thank you.

No one has explained how, comparing their usual new prices, a 1931-33 Imperial only a f i f t h as good as the L-29 Cord’s stablemate, Duesenberg, obsolete two years after its introduction, taking eight years and several iterations to dispatch 480 editions to Hollywooders and look-at-me scions of industrial wealth not put out by a crash box, l o n g camshaft chains that could upset valve timing at high rpm, outrageous service costs for demanding maintenance;

the nine-main-bearinged Imperial lacking only the Duesenberg’s twin cams and cuckoo clock of gears flashing lights at intervals telling the driver it was time to change oil, check battery level, and that the proprietary Bijur chassis lubrication shared with other expensive cars was working.

Engineer, automotive historian Maurice Hendry reported that most Model Js in road trim (3.8, 4, 4.3 and 4.7:1 axle ratios, the middle two most common) topped out at 105 mph, only 10 more than a well-tuned

Imperial. Duesenberg owners wanting the fine tuning involved in the factory claimed top speed of 116 mph (windshield removed, 3.8:1 rear axle, optional 5.75:1 compression in lieu of the usual 5.2) had to pay extra.

Interesting observation how the profiled Imperial shares its mien with the Bentley 8 Liter as both Walter P. Chrysler and W. O. Bentley came from locomotive shops and their engineering honest and respected. Buoyed by more popularly priced lines, Chrysler did not have to resort to blood diamonds to stay afloat.

A wonderfully detailed article on an amazing car! THANKS!

The history lesson given is also priceless.

Most of this particular car’s history took place in my “backyard” — Long Island.

Walter Chrysler is probably the only “Good Guy” among the big auto pioneers.

No union-busting violence or corporate backstabbing.

Just genius engineering and the determination to keep advancing automotive performance and technology.

Even if Chrysler Corporation had gone under back in the ’80’s, the beautifully magnificent NYC skyscraper bearing his name will forever attest to his vision.

(Though almost everyone can picture the Chrysler Building’s gorgeous exterior, it’s definitely worth checking out its interiors; particularly the Lobby and top-floor Observation Room… Breathtaking. Search online.

ABC, right you are on all fronts. While GM’s and Ford’s union opposition became a national disgrace in the late ’30s, Walter P. Chrysler, like Packard, Hudson, Nash and others, saw the inevitable and settled, among the reasons Chrysler was the nation’s second biggest automaker throughout the ’30s and ’40s, and Packard the most widely held automotive stock after on GM (Ford didn’t go public ’til Jan. 1st, ’56).

Chrysler always ate in the cafeteria with his rank and file, always considered himself first a workingman, which he certainly was, an honest one. His tools were long– perhaps still are– on display in the lobby of the Chrysler Building, which most polls of architects show in accord as still the most beautiful spire on Manhattan’s skyline.

The furthest Chrysler went to provide an atmosphere in which his workers wouldn’t follow through with unionization was to put electric signs showing the results of ballgames around the nation up along the walls in the cafeteria.

Henry Ford may’ve given the masses affordable cars, but Walter P. Chrysler gave them affordable engineering, and there was no lovelier heavy iron luxe in the early ’30s than an Imperial.

Alex Kwanten did a superlative job above, and all best to Greg Nowak.

Thank-You for the nod of approval, AND for contributing more fascinating information.

Those “Wunderkind” of the past: Tesla, Kettering, Chrysler and more, weren’t just technical wizards — they also resisted the allure of avarice.