In the Moment: Flute around and find out

Welcome to a new weekly feature we’re calling In the Moment!

This all started in Slack, the messaging software we use for staff communication. Several weeks ago, Hagerty’s editor-at-large, Sam Smith, began kicking off our mornings by plopping a random archive photo into our chat room.

In addition to being a lifelong student of automotive history, Smith drinks a lot of coffee. Each photo he dropped into the conversation was accompanied by a bit of caffeine-fueled explanation.

We liked these drops a lot, so we’re sharing one here each Thursday. Enjoy, and let us know what you think in the comments! —Ed.

**

There are many stories about Soichiro Honda. This one just happens to end in a party.

And $50,000 in booze.

And a year he spent getting his friends drunk and playing the flute.

The guy always seemed so cheery in pictures. Maybe it was all the . . . fluting?

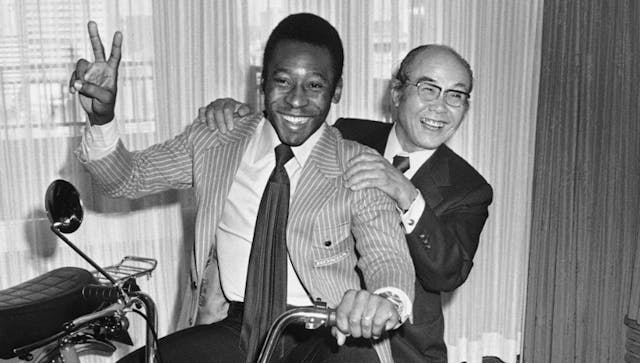

Meet Mr. Honda, Soichiro, the man who built the company. The photo above was taken in 1976, at a Tokyo press conference. The man on the left is Edson Arantes do Nascimento, a.k.a. Pelé, the soccer legend. The man sitting behind Pelé founded, to quote Wikipedia, “a Japanese public multinational conglomerate manufacturer of automobiles, motorcycles, and power equipment.”

Still, Honda was so much more than an industrialist. Just as Pelé was so much more than a guy who kicked a ball.

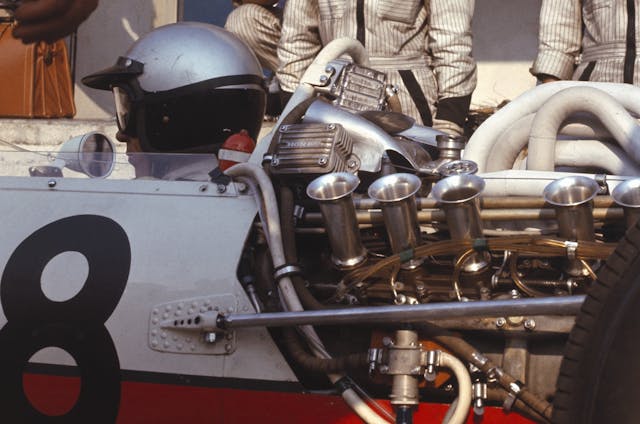

In the Moment traditionally focuses on a single photograph. We pull apart the story behind the image, zooming in literally and figuratively. The photo at the top of this page was taken in 1966. It shows a Honda Formula 1 car in the pits at Monza. The shutter snapped open on the first weekend in September, during the Italian Grand Prix.

I found this picture several years ago, almost by accident, while poking through the Getty Images archive. I saved it for a few reasons. For one thing, it shows Richie Ginther. Ginther was an undersung talent, a one-time mechanic from California who ended up driving Formula 1 cars for Ferrari and winning in F1 for Honda.

Your narrator is a sucker for a good bootstrap underdog.

More important, however, this photograph is Kodachrome. To paraphrase Star Trek, I am and shall always be a sucker for good Kodachrome.

In photography, pigment is never the whole point. Just as black-and-white does not automatically make an image art, color does not guarantee additional emotion or meaning. Here, though, it brings something to the table.

Look at the warmth! That light, the Italian sun in fall! Imagine what these people were thinking: Ginther, in goggles and an open-face helmet, a steely-eyed missile man. Those men at the wall, in those striped suits, focused.

The car is a Honda RA273. That white bundle of snakes behind him is the exhaust for a 3.0-liter V-12. When this photo was taken, that engine design was only a few seasons old, the company’s first powerplant with more than four cylinders. The engineering inside it was little more than a shot in the dark.

Nineteen sixty-six was Honda’s third season in F1. The marque’s V-12 had debuted in 1965, at 1.5 liters. The year before, 1964, the team had been embarrassingly down on power. The twelve was born of men determined to not fall short again. In 1965, with 230 hp, that 1.5 gave Honda more power than any other team on the grid.

Monza is a fast place; modern Formula 1 cars regularly average more than 160 mph over a lap. In ’66, the track was the same basic length but even faster, an undiluted beast. Its 3.5 miles of asphalt held just five corners. (There are currently 11, including three chicanes.) During the ’66 Italian GP, in a 360-horse Ferrari with treaded tires and no aerodynamic aids whatsoever, Englishman Mike Parkes qualified on pole with a 91-second lap. He averaged more than 140 mph.

At Monza in ’66, Ginther finished seventh. Still, the 273 was flawed. Overbuilt out of caution, to withstand the 3.0-liter’s power, it was more than 500 pounds over that year’s rule-mandated minimum weight. Corners were a problem.

Those Japanese mechanics! The dirt! The man at left wears a hint of a smile.

Forgive the digression, but I keep coming back to the power of color. The photograph below was taken in the same place as that Kodachrome shot, on the same weekend. It depicts the same car, the same mechanics—even Ginther, just above the right rear tire.

Same basic lighting, nice composition. A good exposure. But nowhere as powerful, right?

Again, color makes a difference. But only when it . . . makes a difference.

In the mid-Sixties, Formula 1 was not yet an international megasport. It was more like a globetrotting form of well-funded club racing, with some cars built in renowned factories and others from independent shops the size of your house. The many-headed hydras of sponsor money and TV coverage had yet to change everything.

Crucially, Japanese carmakers were not yet a global force in new cars; their efforts sold well at home but were too small and fragile to really succeed overseas. Motorsport was another problem entirely, even without the cultural stigma. Much of midcentury road racing was populated by erudite upper-crusters who thought certain ethnicities didn’t “belong” in certain circles.

The red! The cursive Racing Team on the pockets! The way shadows fold across those stripes! F1 teams did not dress like this.

Four-wheeled grand-prix racing was then 60 years old, but no other Japanese manufacturer had ever stepped to the table. In retrospect, that step could only have come from one firm.

Soichiro Honda founded the Honda Motor Company Limited in 1948, at the age of 42. The brand found international fame building motorcycles. In 1954, Honda the man made a public announcement: His company would soon race its motorcycles at the Isle of Man.

This island, off the western coast of England, is perhaps the most storied location in all of motorcycling. Its annual Tourist Trophy race was first run in 1907 and still runs today. The TT is known for a lot of things—not least a seemingly insatiable appetite for blood—but it is primarily recognized for asking much of rider and machine. Each lap is more than 37 miles, on public roads closed for the purpose. In the 1950s, British and Italian bikemakers had a lock on handling and specific output—power produced by a given displacement—and so their bikes dominated.

Honda wanted to go to the TT because he had always wanted to go. He had dreamed since childhood of racing on a global stage. He would later tell interviewers that he took his bikes to the island because he knew race wins would break open the lucrative American and European markets. Those wins, he said, would help make his company “respectable.”

Fun word, respectable. I like the Google definition: Regarded by society to be good, proper, or correct.

As if that regard were actually the same as being those things.

At Honda, the TT program was given to a man named Kiyoshi Kawashima. He had little racing experience. “Anyone who was a respectable engineer,” Kawashima once said, “wouldn’t have considered getting into anything so reckless as competing in the Isle of Man TT race. As for us, from the Old Man on down, none of us were respectable.”

I laughed when I read that.

Honda entered its first IoM TT in 1959. The event marked the firm’s first world-championship race. The bikes weren’t fast enough. One rider crashed. Kawashima went back to the drawing board. For the next year, 1960, he and his men committed to a full grand-prix season.

The advancement here is remarkable. A year later, in ’61, Honda won two motorcycle world championships. By 1967, the company’s two-wheeled comp department had notched 138 G.P. wins and more than 34 world titles. Its production bikes were selling well in America. The marque was two years away from releasing the 1969 CB750, a roadgoing motorcycle that would essentially birth the term “superbike” and help kill the British motorcycle industry’s market dominance deader than hell.

The race cars, though—they were still a problem.

Naturally, Honda was in Formula 1 because Mr. Honda wanted to go there. Ramp-up was nonexistent. There was no study of lower classes, no steeping in a ladder system of slower race series. Soichiro simply aimed for the biggest game in town. That 3.0-liter V-12 in Ginther’s car represented only the second time Honda engineers had designed an engine larger than 800 cc. (The first was the company’s 1.5-liter F1 V-12 of ’64 and ’65.)

In 2022, everyone knows the Accord and the Civic. Some people know that Ayrton Senna won a few F1 titles in a Honda-McLaren. That Monza shot was early days. It would take years for Honda to become a major player in the sport. Or in carmaking, period—the brand wouldn’t officially start selling new cars in America until 1970.

But What About That Fifty Grand of Booze?

So: We have now a good picture of the man’s motorsport accomplishments. But who, exactly, was he?

Soichiro Honda was born in 1906, in the city of Hamamatsu, about 150 miles southwest of Tokyo. Countless books say things like, “he was fascinated with engines,” or “he believed in the power of dreams.” Nice ideas that tell you nothing about the guy himself.

What does tell you something: In 1914, while in second grade, Honda saw an airplane for the first time. He responded to the sight by going home and making a pair of flying goggles from cardboard. Then he cut a propeller from bamboo and stuck it on the front of his bicycle. The kid then proceeded to “fly” that bike around his town for weeks, goggles and all, terrorizing locals.

As a young adult, Honda moved to Tokyo and became a mechanic. In the 1920s, he built a race car powered by an 8.0-liter aircraft V-8. In the 1930s, knowing little about metallurgy, he founded a company to manufacture piston rings. Quality-control problems appeared early on; Honda worked long hours trying to solve them, virtually living at the factory. He fell into despair, grew his hair long from indifference, became something like a hermit. He would later describe this period as the most difficult time in his life.

Honda had long despised schooling and found formal education frivolous. At a low point with the ring problem, he caved, cold-calling a technical school in his hometown, to ask for help. He befriended a professor at that school and became a student again, attending lectures on engineering.

Nine months after those first piston-ring troubles, Honda solved the problem. The company grew. World War II began. In 1941, Honda’s firm was placed under government control, and Toyota acquired a 40-percent stake.

Near the end of the war, Honda’s factory was bombed heavily. Shortly after, what remained was all but destroyed in an earthquake. In 1945, Japan surrendered. The country was blanketed in despair. Honda’s hard work was literally in ruins, but he made a conscious choice to stay positive. He sold his remaining 60-percent stake in the company to Toyota. What he got in return wasn’t much—around $2.4 million in modern dollars.

As Tetsuo Sakiya writes in his excellent Honda Motor: The Men, the Management, the Machines:

[Then, Honda] announced he was going to spend a leisurely year . . . [he] thought the Japanese were too agrarian-minded and knew of little else but hard work.

Perhaps to demonstrate a more exuberant approach to life, he spent [more than $50,000 in 2022 dollars] on a large drum of medical alcohol. The drum was installed in his house, where he made his own whisky, and he spent the next year partying with friends and playing the shakuhachi (a Japanese wind instrument).

In 1946, Honda started over. He founded a technical research institute. Three years later, he dismantled that institute and used the proceeds to start a motorized-bicycle company. He didn’t know much about motorized bicycles.

A short while later, he pivoted to motorcycles. He didn’t know much about those, either.

Let’s pull all this down to basics:

1. Man faces poor luck but cashes out alright

2. Knowing everyone is suffering, man uses his good fortune to buy his friends an industrial quantity of free booze (a.k.a. flute around and find out)

3. Man decides to keep learning. He builds an ambitious thing, which evolves into another ambitious thing, which then evolves into another ambitious thing

5. Prosperity results, so he thinks, Why stop now?

6. Jump-cut to: The TT win, the CB750, the first Honda Civic, wild success in America, McLaren-Honda, VTEC, the Acura NSX, the list goes on.

***

I am reminded of a quote from the British writer C.S. Lewis. And of an old friend. When I was 25, I took a magazine staff job under an editor named Jean Jennings. It was my first time working at a desk. I was nervous, didn’t know how to behave.

After a few weeks on the clock, Jean pulled me aside. Stop thinking so much about “the rules” of being in an office, she said; just be yourself. That’s all anyone remembers anyway.

Now the Lewis:

“Critics who treat ‘adult’ as a term of approval . . . cannot be adult themselves. To be concerned about being grown up, to admire the grown-up because it is grown-up, to blush at the suspicion of being childish; these things are the marks of childhood and adolescence . . .

Young things ought to want to grow. But to carry on into middle life . . . this concern about being adult, is a mark of really arrested development. When I was ten, I read fairy tales in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am 50, I read them openly.

When I became a man, I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.” —C.S. Lewis

Remember Kawashima, again: None of us were respectable.

People laughed when Honda went to the Isle of Man, laughed when he entered F1 and the American market. As if there was some reason a Japanese company shouldn’t be in those places.

Take your shot. Try the big ask. If everything goes to hell, buy drinks for your friends. Illegitimi non carborundum.

We think we know what will happen if we don’t stick to the rules. That is not always the same as actually knowing.

Have a good day, guys!

—Sam

Great read. My first experience with a Honda was with a first gen civic. My sister bought a new one off the lot with a manual trans. Only problem was she didn’t know how to drive stick. I rode along a day or so after the purchase and pointed her down a nearby street with multiple stop signs in a row. She kept killing the car at the first few takeoffs in first. Then I mentioned give the engine a little more gas as you release the clutch. Next stop sign she revs the engine way up and proceeds to squeal the tires across the whole intersection. I laughed like crazy then and it still brings a smile every time I think about it. Didn’t know that little go cart had the potential to smoke them that much

Nailed it, Sam Smith! Well said and said well!

Thank you!

Wow. Again. More masterful Prose! I had to roll into the rhythm of jumps in time and subject, which of course is what ended up making this such a great Read. My only-so-far Honda confection is a 2012 CRV, but even that is built like a Swiss Watch. And will go, smoothly, forever. Thank you Sam!!

Thank you, Stuart! Really appreciate that.

FTR: These things are written mostly off-the-cuff, stream of consciousness. The technique has pluses and minuses. If the construction ever gets to be a mess, please let us know!

What a great, fun read. My big takeaway from this is less about the impact of the photo, but more about difference between Soichiro’s struggles, and how we sometimes perceive someone so massively successful as having had it easy.

For the previous commenter, my grandfather also used “Illigitemi non carburundum,” though not as often as “Vaksn voltsu vi a tsibele.” But, them’s fightin’ words.

Awesome photos, especially the lead photo and great writing! A few comments after RA272’s win. Shame on me I don’t recall the sources.

Afterwards his (Ginther’s) friend and Brabham driver Dan Gurney remarked that when he walked behind the Honda in the pits as it was warming up … “its exhaust blast nearly tore the legs off my racing uniform. The sheer volume of gas that engine was passing was unbelievable. If that Formula (1,500 cc engine limit) had run another year I don’t believe we would have seen which way the Honda had gone. The rest of us would have been history …”

The car’s fuel injection had played a decisive role in maintaining power at high altitude. Honda has always had a reputation for producing strong engines and for the new 3-litre formula Shoichiro Irimajiri produced a 360 bhp V12. Unfortunately the car was once again let down by being relatively heavy and unwieldy. Noted automotive historian Doug Nye, called it “an engine man’s engine, with little practical thought devoted to the kind of chassis necessary to carry it.” This is in contrast to current practice in Formula One where it’s all about packaging.

Having owned a few Honda’s including an S2000 I really appreciate the mark. Honda ushered in a new era of fuel-efficient vehicles and showed Detroit that it could never, ever get complacent again.