Imperial Dreams: Why Chrysler’s forgotten luxury brand couldn’t make it with the Sinatra set

It feels like the domestic luxury pantheon has been set in stone since nearly the end of World War II. Ford has Lincoln. GM has Cadillac. And Chrysler has … Chrysler, right?

Not quite. For a brief sliver of time, the brain trust at Highland Park did their darndest to push a third premium badge onto the American public, spinning the Imperial nameplate away from the mothership in the mid-1950s right around the time that economic convulsions tipped all but the strongest domestic automakers off the cliff of bankruptcy.

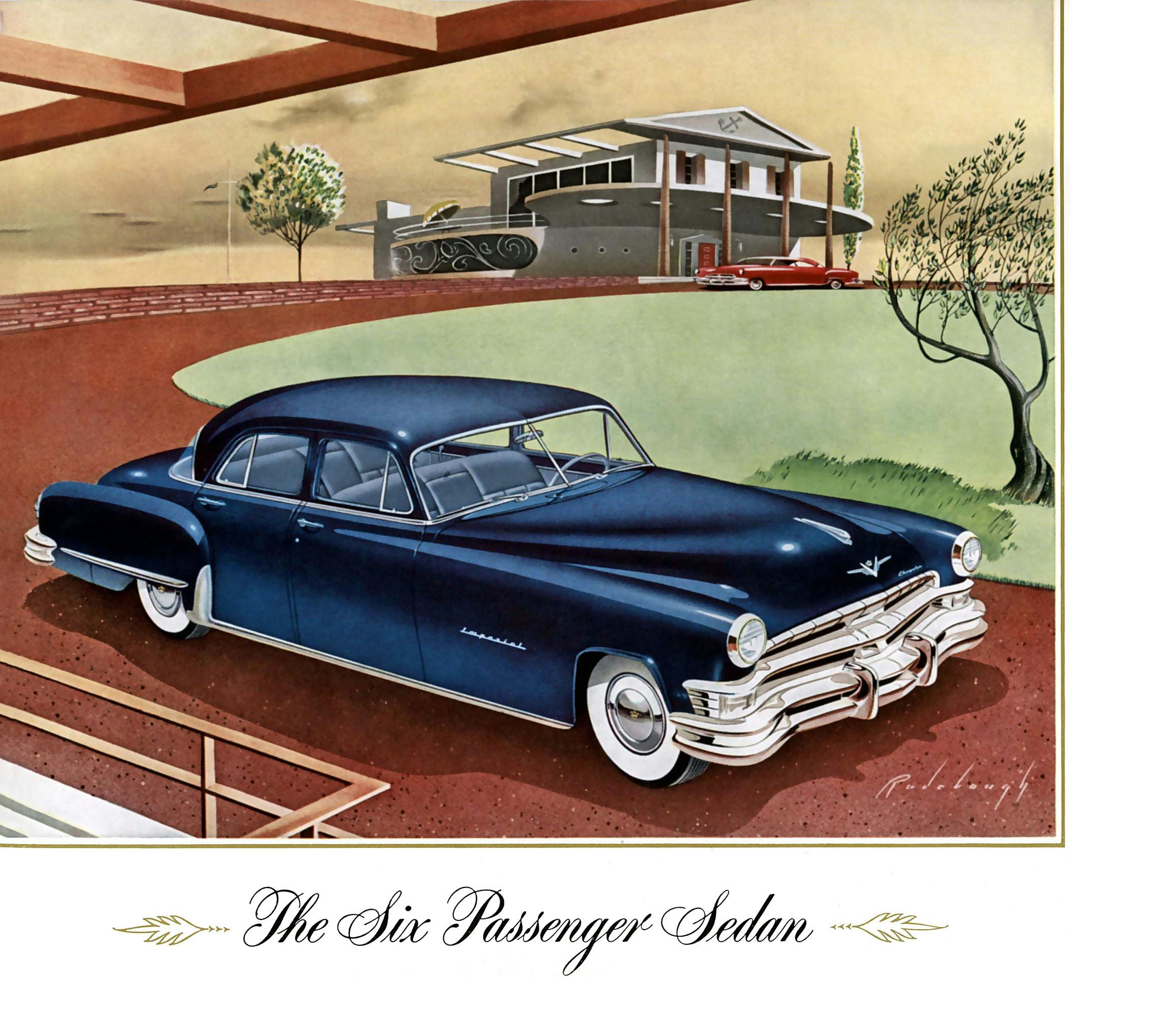

Although the Chrysler Imperial had been around since 1926, this was the first time it was positioned as a stand-alone concern. The gamble was that well-heeled buyers would follow the company’s latest luxury liners as they sailed the same course laid out by Lincoln, Cadillac, and (for a few more years, at least) Packard.

Chrysler was tempted by the fortunes minted by aspirational pricing across town and confident that the Imperial line-up had as much to offer, if not more. The trouble with Chrysler’s Imperial phase, it turns out, had little to do with the cars themselves. Rather, it was the fundamental disconnect between the brand’s executives and their approach to would-be customers, who weren’t nearly as easy to woo as they had first seemed.

Style-first, style-last

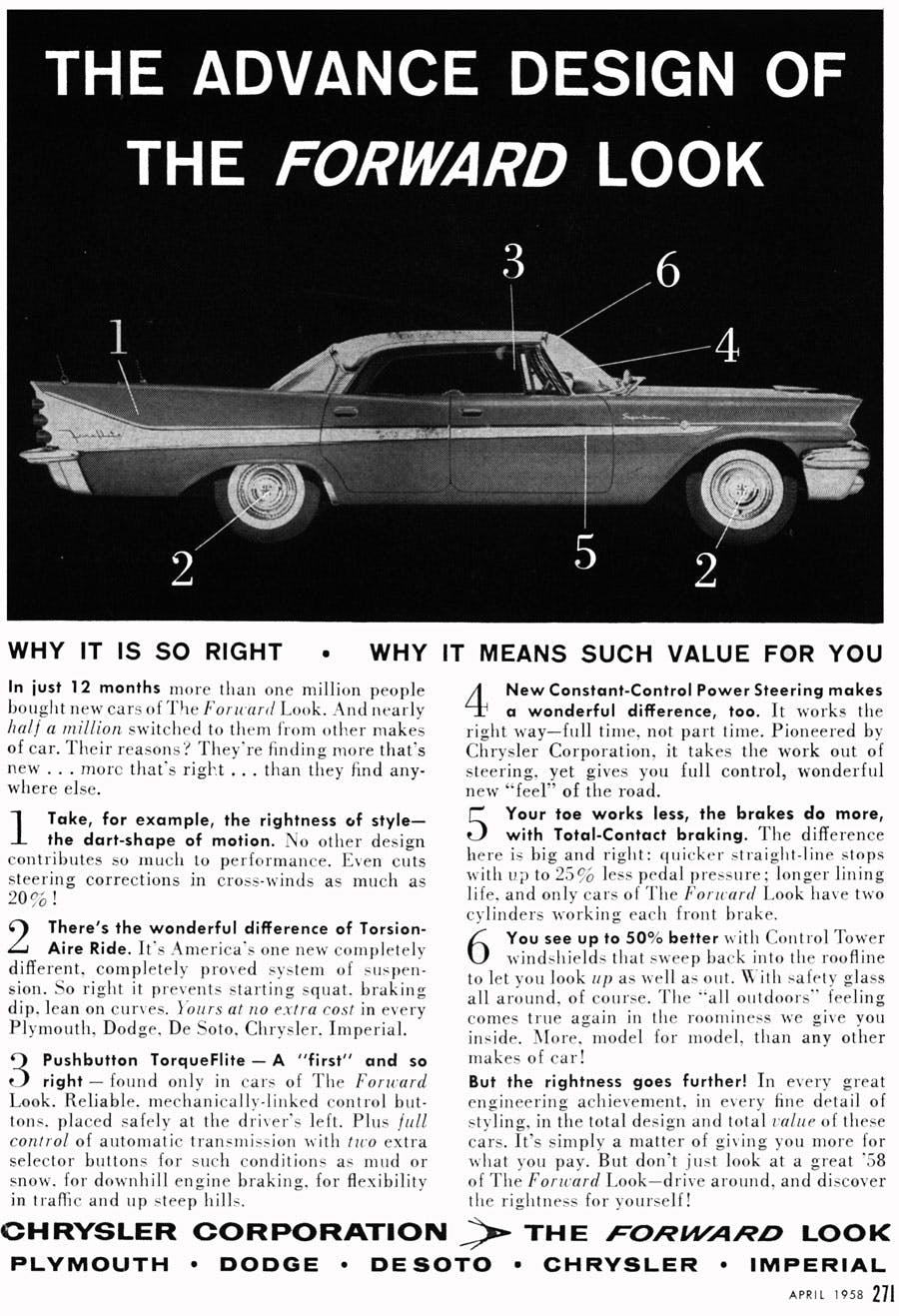

Chrysler timed its Imperial pronouncement to coincide with the company’s full-line redesign that had been nearly five years in the making after newly-minted company president Lester Colbert hired Virgil Exner following his successful stint at Studebaker in the late 1940s. Together, the pair created the Advanced Styling Group, which produced a series of show-stealing concept cars while building up to what became known as the “Forward Look,” Chrysler’s new corporate visage.

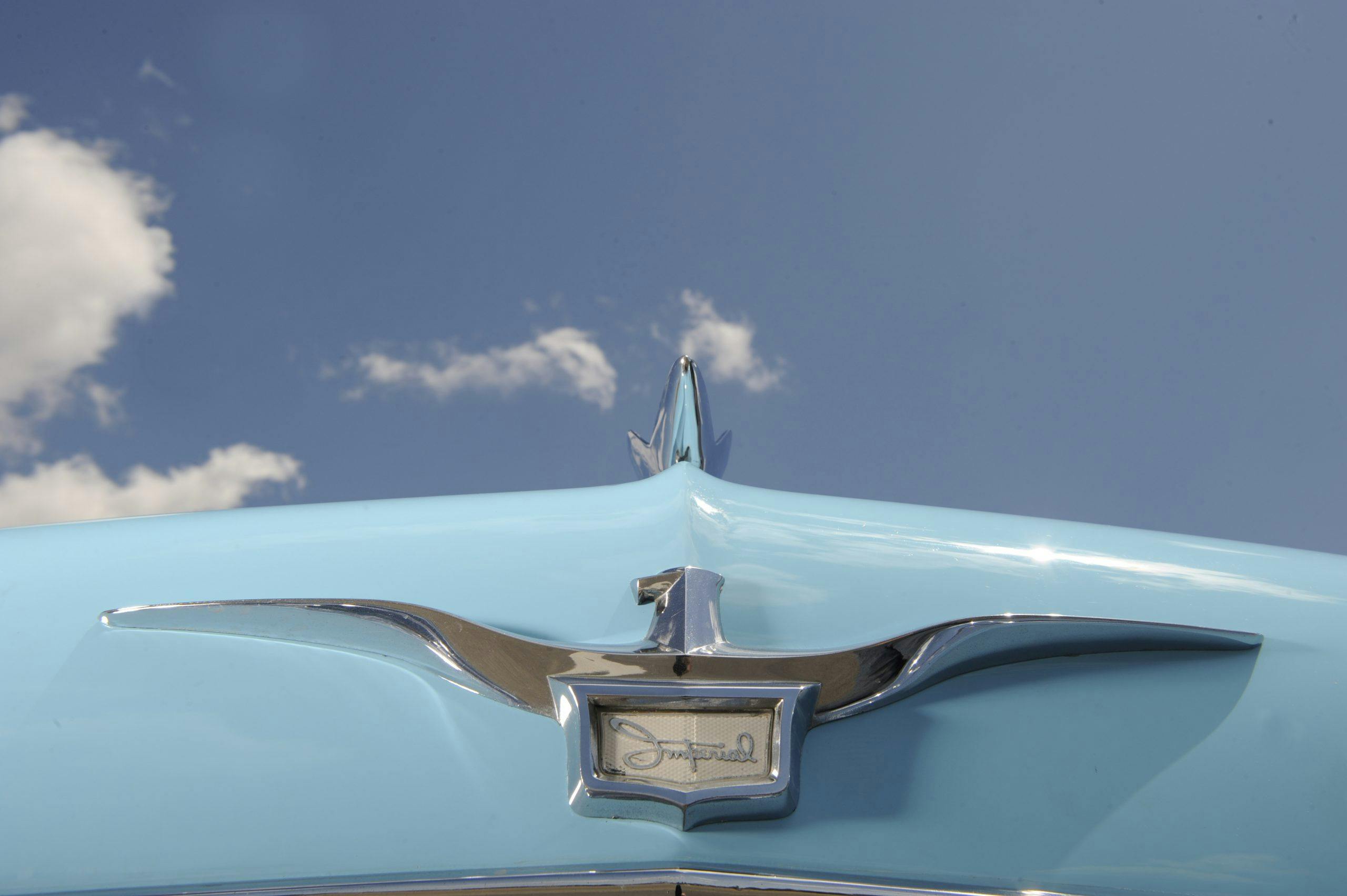

Of the Forward Look cars, Imperial made the biggest splash, making such waves that designers at each of its rivals hurriedly revised their own future full-size plans. It was the beginning of a non-stop assault on the status quo, led by Exner’s crack styling commandos that changed the conversation in the luxury space. “Suddenly, it’s 1960!” crowed Chrysler’s advertising in 1957, and it wasn’t long before the rest of the industry moved on from the overwrought excess of Cadillac’s double-stacked tail-fins (1959 would be their apogee) to the sleeker, more modest sheetmetal that would soon be adopted by GM and Lincoln.

Hemi-powered and hot to trot, Imperial came out of the gate hard. With interiors as plush as its exteriors were unique, the cars were certainly well-positioned to make a dent in the luxury status quo. There was trouble on the horizon, however, and it began where Imperial had started: in the design department.

After a series of health issues, Exner’s time at Chrysler was coming to an end. With a three- to four-year lead from design to production in that era, Virgil simply guessed wrong in 1957 when it came to the actual 1960 model year. He doubled-down on that Imperial’s bulkier, throwback look by adding more ornamental heft to the flagship cars for ’62, forcing them out of step with their peers. Then there was Exner’s growing feud with Colbert, who demanded that Chrysler’s large cars (including Imperial) be downsized for 1962 for fear that General Motors was about to do the same.

Either way, Exner was fired in 1961, replaced by his one-time nemesis at Lincoln, Elwood Engel, who had penned the revolutionary 1961 Continental. A hasty effort from Engel toned down some of Exner’s extravagance, but the industry-wide downsizing rumor proved to be false. Buyers stayed away from the smaller ’62–63 Chrysler, Dodge, and Plymouth models, and didn’t quite know what to make of the Imperial’s unusual proportions.

No dealer blues

All of this behind-the-scenes drama obscured a far more pressing issue with Chrysler’s Imperial gambit. Whereas Lincoln and Cadillac had their own dealer networks aimed at providing a comprehensive experience to customers expecting to be treated with more care than the traditional Mercury or Chevy shopper, Chrysler continued to sell the Imperial alongside its other less upscale fare.

It’s a trap that continues to ensnare nascent luxury car brands—witness modern-day Genesis and its struggle to separate from Hyundai’s existing stores—but it’s hard to see Chrysler’s unwillingness to commit to proper Imperial outlets as anything other than an attempt to take on Cadillac on the cheap. Signage simply wasn’t enough to convince those willing to foot the car’s eye-watering window sticker that they would be insulated from the rabble across the showroom.

It became a self-fulfilling prophecy, as the absence of a real profit stream from the Imperial lineup convinced executives that they were right to avoid investing any more capital in a separate marketing strategy. And yet at the same time money continued to be poured into Imperial on the design and production side, which in the 1960s began to float its way through luxury land in a pool of red ink.

Marching towards anonymity

The Imperial forged ahead, retaining its body-on-frame platform as the rest of Chrysler adopted unibody construction in the early 1960s. In fact, the Imperial’s original frame stayed in the picture from 1957 all the way to 1966, isolating it from the rest of the automaker’s lineup in terms of chassis technology (although it continued to receive the requisite drivetrain upgrades as the automaker cycled Hemi, wedge, and other assorted big-blocks through the rotation).

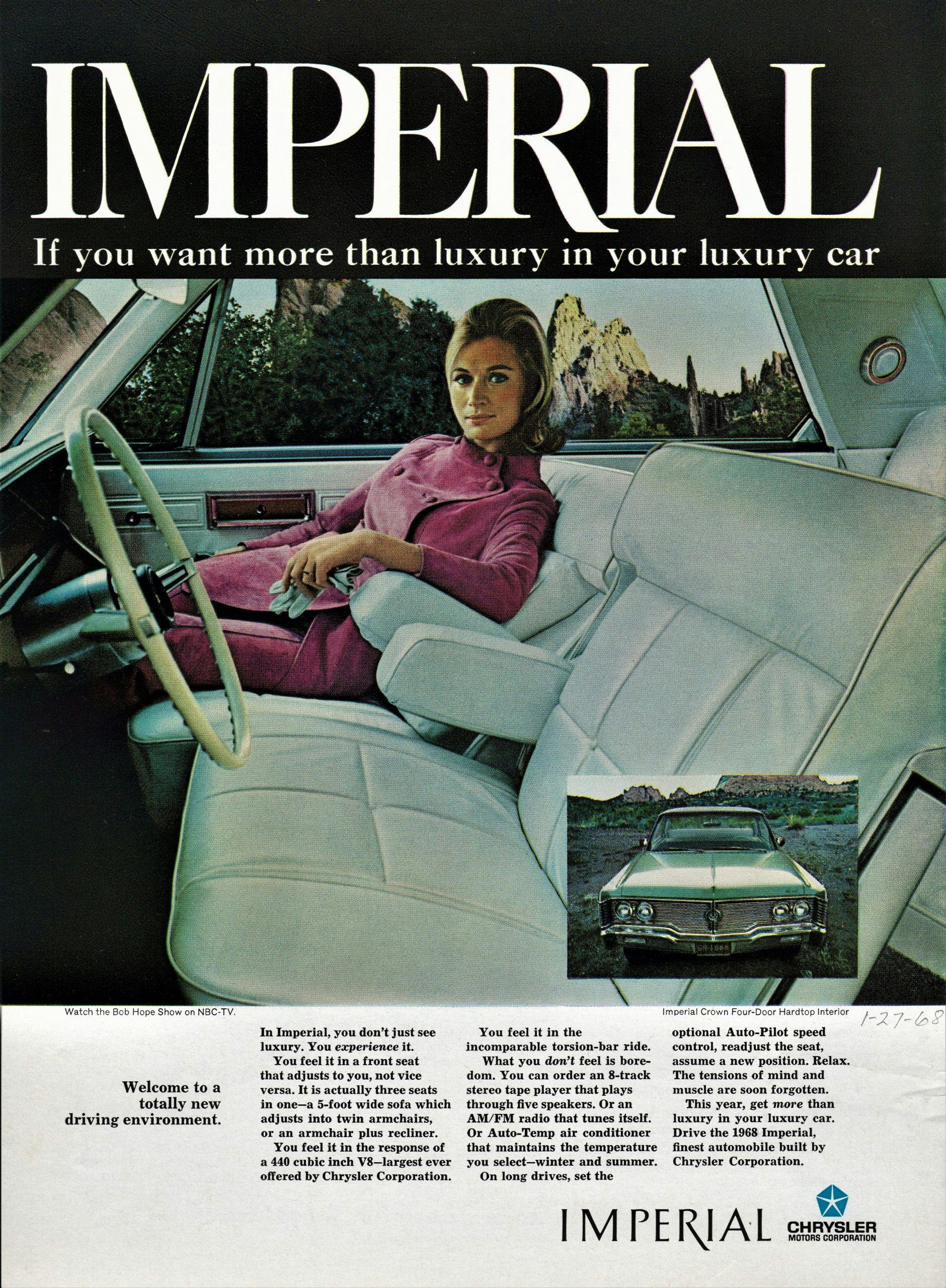

Engel guided the Imperial through a series of updates that hewed closely to his slab-sided Continental roots, placing greater emphasis on the Crown trim level but generally keeping the car conservative. At this point, sales were less than half what they had been at its peak, with roughly 12,000 to 13,000 units expected to find new homes in a given year.

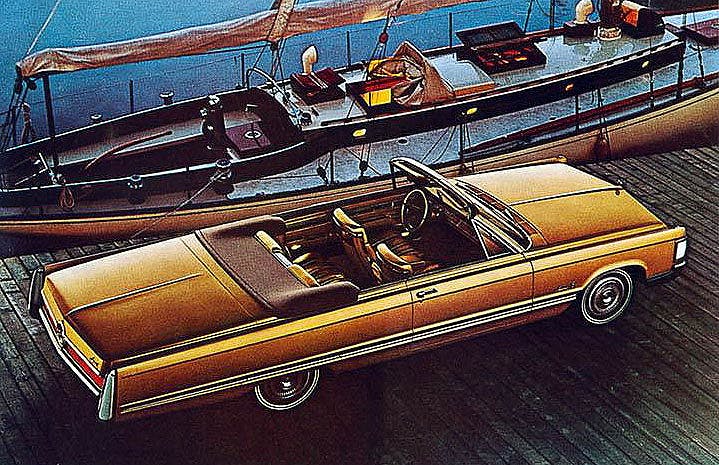

By the time Imperial moved to Chrysler’s full-size C-body unibody in 1967, it was as much for cost savings as it was modernization. One had to squint to detect the difference between the Imperial and the New Yorker, whether in coupe or sedan form (although the pricier of the two was indeed longer and featured revised front and rear styling). It was the beginning of the end for the Imperial’s styling independence: It followed the rest of the Chrysler full-size cars into fuselage land in 1969, and by the time it was axed in 1975 (with sales nearly halved once again) it was easily absorbed into the New Yorker portfolio the following year.

Identity bereft

Chrysler made three attempts to salvage past Imperial glory, with the first being a 1981 rebody of the Cordoba coupe. Not even the inclusion of a limited Sinatra Edition (complete with a stack of the Rat Packer’s tapes and a paint palette daubed from Ol’ Blue Eyes’ own iris) could sway more than a few thousand customers a year before it was unceremoniously dumped after 1983.

Even more cynical was the K-car based Chrysler Imperial (1990–93) that relied on deep discounting to move five times as many models to buyers who no doubt instantly regretted their decisions. A 2006 concept put the marque to bed after DaimlerChrysler’s troubled ownership situation and the global financial crisis of just a few years later stuck a pin in the idea of a new luxury sedan from the Pentastar.

While it’s clear as to why no one is lining up to plunk down big auction money on Cordobas-in-cosplay, and it’s not surprising that ’70s-era Imperials remain radioactive to collectors uninterested in Malaise-Era me-toos, it’s much more puzzling as to why the first-decade Imperial run has remained so invisible on the classic car market. Current values on first-year 1955 Imperial Crowns touch six figures for a concours-quality example, but by 1964 that figure quarters to just over $21,000, reflecting the less-flamboyant styling shift despite sharing the same general platform (and offering a better driving experience). Similarly weak interest in ’60s-era Imperials can be found outside of a handful of scattered, low-production trim levels.

Chrysler’s inability to communicate to the general public why they should desire an Imperial, and its unwillingness to spend more than a token amount to counter the brand-building of both Lincoln and Cadillac, resonates to this day. With no heritage or folklore to carry it through the same lean times and corporate mismanagement that its competitors survived, Imperial has almost zero cachet among even those who grew up while it was a going concern. It’s impossible to truly answer the question “what is an Imperial?” and perhaps for that very reason, few today even ask it.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece referred to Chrysler’s current corporate base in Auburn Hills, rather than the historical Highland Park location.

I grew up when Imperial was made. I always wanted one. I still do but I have Multiple Sclerosis now and seldom drive. Imperials were always beautiful to me. Im sorry that you don’t see it. My absolute favorite was a 1974/1975 Imperial LeBaron two door hardtop. It had hidden lights, hidden wipers, fender skirts, an eagle hood ornament, great hub caps, integrated metal bumpers, vanilla top, frenched rear window, vehicle tail lamps, pillow interior seats, four wheel disc brakes and the list goes on. It’s probably too late now for me, but that Imperial was so elegant. I wish that I had one.

Although we all know the 81-83 model’s horrible efi set-up’s reliability killed it but in sheer look and presence i.m.o. was way better than the Mark VI coupe and Eldorado it competed against. Let’s not forget that Cadillac’s V8-6-4 was just as awfull reliability wise and the HT4100 wasn’t much better. Chrysler just didn’t have the financial ressources to re-engineer the efi set-up while going full k-car to save its own skin from bankruptcy.

“Buyers stayed away from the smaller ’62–63 Chrysler”….. Wrong. The 62 Chryslers were not downsized and were exactly the same size as their 61 counter parts.