How one man destroyed French luxury car makers

When you think of great automotive countries, France usually gets mentioned somewhere after the United States, Great Britain, Germany, Japan, and Italy. The truth is that France has been an automotive pioneer.

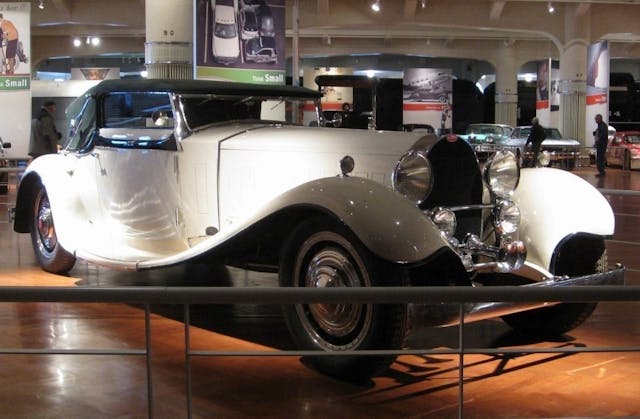

The traditional layout of front-engined rear-wheel drive cars is known as the System Panhard, after the French company that originated it. Likewise, the driveshaft-based Hotchkiss Drive, was how most 20th century automobiles were propelled. Citroën’s Traction Avant was arguably the first practical and commercially successful front-wheel drive automobile. Mathis is attributed with making the first all-aluminum car. In the 1930s, French luxury brands like Delahaye and Delage represented the apotheosis of Art Deco, and those marques continue to win high awards at the most prestigious concours. Ettore Bugatti, maker of what are considered the greatest cars of all time, had his atelier in Molsheim, in France’s Alsace region. Those French luxury brands are long gone (today’s Bugatti is a replica of the original, a vanity project of Ferdinand Piech).

What happened to those grand marques? Was it the Great Depression? No, most of the French luxury car makers survived the depression of the 1930s, and although they struggled, that decade was when those companies likely made their best products. Was it World War II? No, most of the French luxury car manufacturers were still in business when the Allies liberated France from the Nazis.

While those companies survived the Great Depression and the Second World War, they didn’t survive the plans of one man, Paul-Marie Pons.

The immediate postwar period was difficult for automakers worldwide. Germany, Italy, and Japan were in ruins. Britain’s factories had been bombed. American automakers were intact, but they faced the task of switching back to making cars after five years of producing armaments. Simply getting the material goods needed to manufacture automobiles was problematic. The War Production Board in the U.S. and the Combined Production and Resource Board in the U.K. continued to control the allocation of steel, rubber, and other commodities into the postwar period. American automotive startups like Tucker and Kaiser-Frazer struggled and scrambled to get materials. As steel was still allocated, smaller British automakers and specialists turned to aluminum—since war production had wound down, the aircraft industry was using less of it and there was no shortage of easily recyclable scrap aluminum littering the English countryside following the Battle of Britain. Automakers on both sides of the Atlantic started exploring a new material, glass-fiber reinforced plastic, GFRP, or fiberglass as we call it in the U.S.

During wartime, strategic materials must be allocated according to defense needs. In peacetime, however, central planning can be a roadblock to innovation. It doesn’t matter to some central planner that you have an innovative idea. The bureaucrat has already allocated the machinery and materials you need to an existing firm with a government contract.

After liberation, France was ripe for central planning. The provisional, transitional government set up after the Germans were expelled and the Vichy government collapsed was a three-party coalition joining the Christian Democrats with the Socialists and Communists. It was in power from 1944 until late 1946. With Socialists and Communists dominating the government, it’s not surprising that France embraced a centrally planned economy.

Influential economist Jean Monnet was put in charge of modernizing and reconstructing the French economy, and Paul-Marie Pons was tasked with rationalizing the French automotive industry. Pons had trained as a naval engineer and before the war had worked as an engineer and manager. After the war he was appointed to the Ministry of Industrial Production, under minster Robert Lacoste, a leading socialist politician.

In the aftermath of WWII, France had 22 car companies and 28 truck makers. Monnet and Pons thought that there were too many companies in those markets. In a manner that has been described as arbitrary and authoritarian, under Pons’ five-year plan seven companies were favored: Citroën, Peugeot, Renault, Berliet (a maker of military vehicles in addition to cars, trucks, and buses), Panhard, Simca, and Ford’s French subsidiary.

Renault and Citroën were allowed to operated autonomously, as they were considered large enough and strong enough on their own. Peugeot was required to join Hotchkiss, Latil, and Saurer for truck and commercial vehicle production. In the Lyon region, Berliet was required to link up with bus manufacturer Isobloc and Rochet-Schneider, which made commercial vehicles. Smaller manufactures than the favored seven were grouped together under Panhard at the U.F.A (Union Française Automobile) and Simca at the G.F.A (Générale Française de l’Automobile), each assigned only one vehicle.

In other words, not only did the Pons Plan tell which companies had to link up with other companies, the French government decided who would make what.

Passenger cars were divided into three main groups, according to vehicle size and market segment. Citroën, with its front-wheel drive Traction model, would would sell larger, expensive cars. Renault and Peugeot would produce mid-sized, mid-priced cars, leaving the less profitable small car market for Panhard and Simca. That small car would be versions of the A.F.G. (Aluminium Français Grégoire), a radical front-wheel drive aluminium based car designed by Jean-Albert Grégoire. Luxury specialists would concentrate on the export market, to help with France’s balance of trade.

Things don’t always go according to plan. After the war, Renault came under the control of Resistance veteran Pierre Lafaucheux, who simply ignored the Pons Plan. The small 4CV’s development was well underway before the war, so Lafaucheux went ahead with launching it in 1948. That left mid-size cars to Peugeot. Simca (Société Industrielle de Mécanique et Carrosserie Automobile) was controlled by a foreign company, Fiat, and located in the west of France, far from Paris, and they too ignored Pons. That left Panhard with the A.F.G, which was rebranded as the Panhard Dyna X. For its part, Citroën, which had been assigned large car manufacturing, went ahead and developed a small car that is quintessentially French, the little 2CV, also developed before the war and launched in 1948. In case you’re wondering why Renault and Citroën sold cars with similar CV brands, CV stands for chevaux, the French word for horses, and is related to the displacement and horsepower taxing scheme.

While the larger car companies, which were favored by Pons, did not quite follow his plan, by the time the government fell in late 1946 and Paul-Marie Pons was out of a job, the French vehicle market and the industry that served it were forever changed. The impact would last longer than five years, with clear winners and losers.

The winners were the four big companies which ended up dominating the French automobile market over the next 25 years: Citroën, Renault, Peugeot, and Simca.

The losers included Panhard, formerly a maker of stylish, large, expensive cars, now consigned to making a complicated small car that was expensive to make. In 1949, Panhard sold fewer than 5000 vehicles, less than 10 percent of the volume at Renault and Citroën. The use of relatively expensive aluminum, and an arithmetic mistake by Jean Panhard, the managing director and company founder’s son, in calculating its cost put Panhard in precarious financial situation from which it never really recovered, eventually selling off, bit by bit, it’s car operations and equity to Citroën, which discontinued Panhard passenger cars in 1967.

Small luxury car makers faced the dual problem of being restricted in their home market and trying to sell expensive cars in a war-torn Europe. While wealthy and neutral Switzerland survived the war with its economy intact, French luxury automakers had to compete with high-end manufacturers in Britain, Italy, and even Germany as it rebuilt in the 1950s. Americans and Canadians had money to spend, but they were already served by American automakers capable of producing huge volume.

Also into the 1950s, while steel was no longer a controlled commodity in France, tax policies enacted in the late 1940s started taking a toll on makers of larger cars, with an almost punitive annual tax on cars with engines larger than about two liters displacement. Once again a large company was favored as the displacement limit was just above what Citroën was featuring in its larger cars.

France’s smaller-volume makers particularly suffered in the wake of the Pons Plan. During the war, Émile Mathis had to go into exile because the Vichy government collaborated with the Nazi occupation forces when it came to Jews. He returned in 1946 and spent considerable sums rebuilding his factory in Strasbourg, which was bombed during the war as the Germans used it to make military engines and munitions. As a matter of fact, in exile Mathis himself had given the Allies the plans to his factory so that it could be more effectively destroyed. At the 1948 Paris Motor Show, Mathis revealed a modern six-cylinder sedan called the Type 666, but steel supplies were still controlled by the government. In the end, the Type 666 was never built, and the factory was sold to Citroën in 1953. In 1956, Émile Mathis died after a fall from a Geneva hotel window.

The displacement taxes severely affected Talbot-Lago, which closed its doors in 1958 and sold the Talbot brand to Simca.

Licorne, another small luxury car maker, showed new 8CV and 14CV cars at the 1947 and ’48 Paris shows, but like Mathis, they could not get the steel to go into production with them.

Rosengart and Samson, which survived the war by making military materiel, found their transistion to peacetime production stymied by Pons’ “preferred producers list.”

That leaves us with Bugatti and Delahaye, arguably the makers of France’s best cars in the 1930s.

The war left Etore Bugatti’s Molsheim factory in Alsace in ruins, and he lost control of the property. He had planned a new factory closer to Paris in Levallois, and he designed a series of new cars after the war, which he called the Type 73, to be made in both road and racing versions. But he was only able to complete five of the series. Just seven of the Type 101 were built. Plans to build a small car, powered by a supercharged 375cc engine, died with Etore Bugatti in August 1947. Without either Ettore or Jean Bugatti (who died in a prewar car accident) at the helm, the company declined and was out of business by 1953.

As for Delahaye, which also owned the Delage brand, the tax on large displacement cars was hard on its domestic-market sales. In 1947, Delahaye sold fewer than 70 cars in France, with 88 percent of its total production of 573 vehicles being exported, mostly to French colonies in Africa and Asia. Also, while the company was advanced in the 1930s, it struggled to keep up technologically in the postwar period, so in the case of Delahaye, its eventual demise cannot be attributed solely to the Pons Plan, but the Plan didn’t help. While production of the respected Type 135 was restarted in 1946 to generate some cash flow; by then the prewar design was considered obsolete, but Delahaye didn’t have much in the way of alternatives or money to create them. The new Type 175 and its variants, all planned before the war, were also outdated by the time they started production in 1948, as production was again impacted by material shortages. Also, the Type 175 had some serious quality issues, as in catastrophic failure of suspension components. The new models did not generate sufficient sales to recover costs, so they were discontinued in 1951.

Delahaye struggled moving forward, surviving by making military vehicles (despite the Pons Plan, the French army still needed vehicles) and a small number of trucks. In 1953, an updated version of the Type 135, branded as the Type 235, was introduced, but only 84 of those were ever built.

Hotchkiss, Delahaye’s main competitor, also survived by making military vehicles, in its case the Willys MB Jeep under license from Kaiser-Willys. It was cheaper and simpler than what Delahaye was making for the French army, which canceled Delahaye’s contract. Layoffs followed at Delahaye. In 1954, Hotchkiss merged with Delahaye, which was somewhat ironic in that Hotchkiss building Jeeps under license hurt Delahaye financially, making the combined company less viable in the long run. In mid-1954, Hotchkiss took over Delahaye and shut down car production there but continued to sell trucks under the Hotchkiss-Delahaye brand. By the mid 1950s, France’s most prestigious prewar car makers, Bugatti, Hotchkiss, Delahaye, and Delage were gone.

While all of the failures of French automakers in the 1940s and ’50s cannot be put at the feet of Paul-Marie Pons, it is certain that the Pons Plan put most of them in a precarious situation, favoring large, politically connected firms over many of the companies that established France’s reputation as a world-class automaking country. Maybe there’s a lesson for our current atmosphere, in which fossil fuels are disfavored and electric vehicles promoted. Sometimes it might make more sense to keep politicians out of the loop and let producers and consumers decide what’s good for the market. Perhaps better Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” rather than the government putting a few fingers on the scale.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Amen to that conclusion.

CV doesnot exactly means horse power. It means chevaux vapeur, a unit used as rating for tax purposes

Thank you for your clarification. With apologies to Madame Arsenault, my high school French teacher, I should have been more precise. Chevaux itself means horses. Chevaux Vapeur means “steam horses”. Since the CV tax scheme was initiated in 1913, that’s probably a reference to steam powered vehicles. Your comment prompted me to do some research. For the period in question CV was calculated based on the number of cylinders, the bore and stroke, and engine speed. Apparently, even though the term refers to horses, horsepower was not part of the calculation. The current French fiscal tax on cars is based on CO2 emissions and horsepower.

Arbitrarily picking winners in free enterprise is just one reason Americans have opposed socialism every time it’s been attempted.