How Exner, Elvis, and DeLorean revived Stutz with a Grand Prix

Please welcome to these pages Jack Swansey! Jack holds a degree in anthropology with a focus on car culture, and he is the world’s leading ethnographic authority on NASCAR fandom (by default, if you must know). His love of the automobile fuels him to discover what cars mean to the people who own, drive, and love them. Join him in plumbing the oily cultural depths of our hobby, and maybe you’ll emerge with his particular appreciation of vehicular perfection incarnate: the third-generation Acura TL Type-S. —Eric Weiner

In January 1970, at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel, Stutz Motor Car of America unveiled one the most expensive cars in the world. At $26,500, the 1971 Stutz Blackhawk cost about the same as the average American house. It was a 19-foot monument to mid-century opulence. Handbuilt in Italy by Ghia, the concept’s bodywork was coated in fourteen layers of lacquer. Free-standing headlamps and vertical grille evoked prewar Art Deco design, while the ersatz side-exit exhausts spoke to contemporary performance trends. Interior trim was 18-carat gold and burled walnut with a Learjet radio—the best that money could buy. Seats fitted in English leather. Headliner and carpets from fine Australian lamb’s wool. Even the keys were gold-plated. Not since the finest days of Cadillac did an American marque so aspire to rival Rolls-Royce.

And yet, beneath all of that glam, this high-roller’s dream machine shared its bones with the Pontiac Grand Prix.

How did the world’s most expensive car end up on GM’s new G-body platform, with a big-block 455-cubic-inch V-8 and Turbo 400 automatic transmission? Well, in 1961, Esquire magazine commissioned ex-Studebaker and Chrysler designer Virgil Exner to imagine 1963 model-year cars from long-defunct American marques Duesenberg, Mercer, Packard, and Stutz. Exner was hired almost immediately to bring one of those designs to life: the Duesenberg. But before the project got off the ground, in 1966, the Duesenberg took back the rights to its family name.

The Stutz name, however, had entered the public domain. Stutz got its start in 1911 with the high-performance Bearcat—an early, very successful sports and racing car of the pre-war era. The Bearcat was highly regarded, featured prominently in F. Scott Fitzgerald novels. By 1924, Stutz had refocused its efforts on the luxury market, but production halted in the mid-’30s and the business was ultimately forced into bankruptcy in 1937.

Financier James O’Donnell, an investor in the planned Duesenberg revival, still believed there was a place in the market for an ultra-luxe Stutz on American roads. He bought rights to the brand name in 1968 and soon hired Exner to pen the first new Stutz since 1934.

For ease of maintenance and production, Stutz would source a domestic platform. With the approval of Pontiac supremo John Z. DeLorean, Exner and O’Donnell settled on the new-for-1969 Grand Prix. Units allocated for metamorphosis were shipped from Detroit to Carrozzeria Padane outside Turin, where nearly every part was stripped in preparation for Stutz-ification.

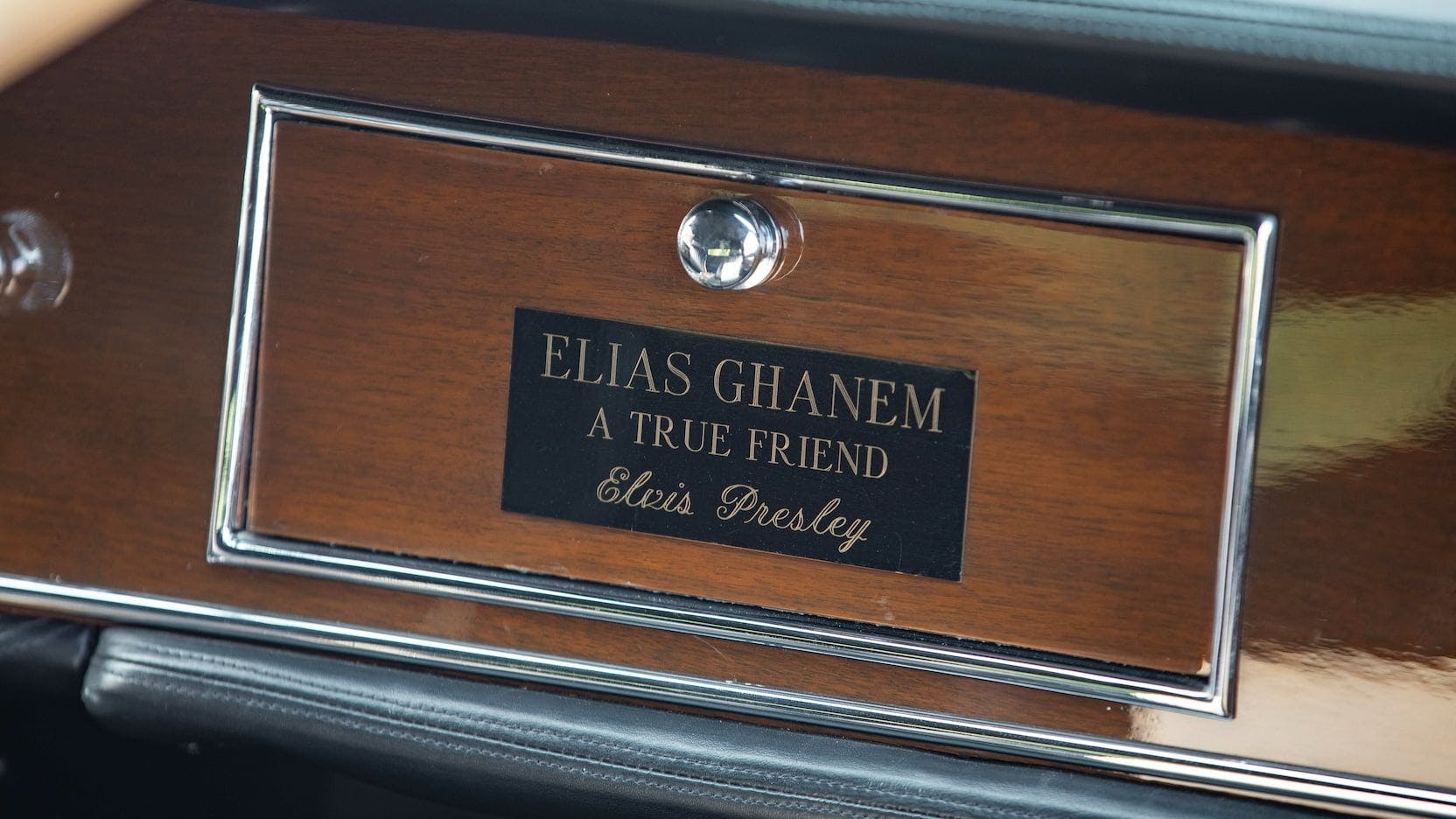

After the Blackhawk body parts were painstakingly constructed and fitted, the cars were shipped to Jules Meyers Pontiac in Los Angeles. Meyers was the lone Stutz dealer on the planet, selected in large part because of his access to celebrity clientele: Liberace, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., and of course, the King, Elvis Presley.

Elvis first became aware of the new Stutz when Meyers, on a tour of Beverly Hills soliciting orders from the Hollywood glitterati, showed up at his house behind the wheel of Blackhawk prototype No. 2. “The King of Rock and Roll” was so enamored he offered to buy the car then and there.

That presented two problems. First, Meyers wasn’t done with the prototype yet; he planned to show it to more potential customers and display it at the Los Angeles International Auto Show. Second, and perhaps even more awkwardly, Meyers had already promised the car to Frank Sinatra.

Then again, Elvis was offering to pose for promotional photographs, something Sinatra was unwilling to do. So, for $26,500, (about $200,000 today) Meyers sold Elvis the Blackhawk. With one monumental sale, Stutz cracked the celebrity market.

Through the mid-1970s, a Stutz was used in everything from Gone in 60 Seconds to Columbo as a vehicular stand-in for wealth. And with record-breaking prices (a 1976 D’Italia convertible sold for $129,000) and a long list of famous owners (Evel Knievel bought one), Exner and O’Donnell had achieved their goal—at least at first.

History’s most famous Stutz was the fourth and final example in Elvis’ collection: a black Series III, reportedly the only car he personally drove between 1973 and his death. Just past midnight on April 16, 1977, Elvis drove the Blackhawk through the front gates of Graceland after a late-night visit to the dentist. Indiana tourist Robert Call snapped a picture as the car passed by. It was the last photograph taken of Elvis Presley alive.

Despite the lofty price tags and reliable GM running gear, Stutz’s finances were dire. Buying new Pontiacs and shipping them to Italy to be thrown away and rebuilt by hand, then flying them back to California, was not a sustainable business model. (Cadillac eventually learned this the hard way, too, with the 1990s Allanté.) O’Donnell lost $10,000 on each of the 25 Series I Blackhawks sold in 1971; in response, some of Stutz’s excesses (in production, at least) were pared back for 1972.

Stutz switched coachbuilders to Carrozzeria Saturn for the Blackhawk Series II. The process was reworked to utilize more componentry from the donor Pontiacs, including the rear bumper and windshield. Only the Stutz’s first 27 Blackhawks ultimately used Exner’s split windshield and spare tire integrated bumper, and subsequent models were much more structurally similar to other GM G-body vehicles.

Stutz suffered other painful losses. Exner passed away in December of 1973, Meyers’ dealership closed by 1976, and Elvis left the building in ’77. The glory days were over for Stutz Motor Car of America. As the decade of disco gave way to a new era of synth-wave, the neoclassic Stutz, replete in gold plating, began to look horrendously out-of-date in a world gone modern.

After 1979, Stutz expanded options from mink carpeting and clocks embedded in the steering wheel to include armor plating, machine guns, and thrones, as Stutz’s aesthetic still resonated with overseas royalty. Most of the brand’s armored limousines and Suburban-based 4×4 convertibles went to the Saudi royal family or King Hasan II of Morocco.

Including the final 12 composite-bodied Bearcat II convertibles, (two of which sold to the Sultan of Brunei) it is estimated Stutz built around 600 cars between 1970 and 1995, all converted from various GM donor vehicles. And that was that.

With its emissions-sapped V-8, ornate kitsch, and gilded dedication plaque for whatever influential original owner ordered it, a Stutz Blackhawk is a definitive child of the Seventies. A car so tied to its moment was perhaps doomed to be bested by the march of time and progress, relegated from luxury supremacy to a footnote in the history of the American automobile. Today, it’s oddball—a coachbuilt Italian classic you can find parts for at AutoZone.

Elvis’ second Stutz, a 1971 Blackhawk I, is set to be auctioned off this November at Mecum in (where else?) fabulous Las Vegas. Even with the celebrity connection, we have a feeling it won’t reclaim its title as the most expensive car in the world.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

Jack, welcome. You must not be even slightly familiar with Los Angeles, if you misspelled Jules Meyers.

Not sure who “Jules Meyer” was, but he wasn’t the entrepreneur of Los Angeles Pontiac and Stutz fame.

You made your point in your first sentence. The second is a needless flourish. If you’ve already indicated a misspelling, asking who “Jules Meyer” was is just twisting the knife.

I saw one of these Stutz’s at a car show, and the description said it once had been owned by Sammy Davis Jr. I remember thinking, why would Sammy Davis Jr drive a kit car? Now that I understand the car’s history I get it. Great article.

That’s an ugly car. I’d rather have the Grand Prix unmolested.

I agree. Not only was that car beat with an ugly stick, the entire forest fell over on it and caught fire!

I’ll stop short of calling ugly but I agree the unmolested Grand Prix was more attractive. More “cohesive” if I may say so.

Jack. Fred died in 1932. Made you are thinking of his son Denny

Screams pimpmobile, love it a car should look like a face in front round headlights and egg-crate grill. With chrome and a little gold to set it off. I am thinking 75,000+ at a action. A 30’s car with modern 70’s components you can get at local parts store. I would drive it.

I can’t believe no new car cost more than $26,500.00 in 1970. I remember a Corvette on the showroom floor for $6,000.00 + in 1971 and a Rolls Royce at the auto show for $31,000.00 a few years later. I built a scale model of this car from a kit in the early 1970’s.

No need to read beyond the foolish statement about it being the most expensive car in the world in 1970. Rubbish.