How a secret 21st-century 7.0-liter Ford V-8 reached 9000 rpm

During the early development days of the Ford “Boss” 6.2-liter V-8, Les Ryder, then Ford’s chief engine engineer, settled on an ambitious development goal (and a catchy phrase): 7000 rpm, 700 hp, and 7 liters. The Triple Seven, as it became known, is one of those what-ifs that could have changed the path of automotive history, especially as the late-model horsepower wars returned at the end of the 2010s. It never saw production—but in the hands of a secretive team, it did see an eight-second quarter-mile a few years ago.

Ford’s 6.2-liter V-8—internally dubbed “the Boss” after the innocence of its first name, Hurricane, was stolen by Hurricane Katrina—was the truck engine Blue Oval fans had demanded since the death of the 460-cubic-inch big-block. The Modular family of engines were serving their roles as durable and efficient powerplants in the Mustang, Crown Victoria, and F-series trucks, but even in tall-deck, 5.4-liter form, they lacked the displacement needed to match the low-end torque of big-cube V-8s from Chevy and Dodge. The biggest limitation for the Modular design, and even for its Coyote successor, was its relatively close bore centers, which dictate both an engine’s valve diameters and its maximum bore size. Knowing this, Ford began developing a new Boss in 2005, determined to build a larger-displacement engine with wider bore spacing to provide the necessary lung capacity.

Ultimately, the Boss 6.2-liter was relegated to utilitarian use in Ford’s pickups (notably, the first-gen 2010–14 SVT Raptor). Imagine if Ford had stuck with the Triple Seven program, which not only beat its horsepower and rpm goals handily in the production-intent 16-valve configuration but also flirted with becoming a true giant-killer with four valves per cylinder. That’s the parallel universe in which the Triple Seven thrived at the hands of Don Bowles, Sr., Ford Racing, and Roush.

Factory speed

While we probably won’t see manufacturers pursue racing quite as fervently as they did in the ’60s, contemporary OEMs still work hand-in-hand with racers to root out the next hot tech and study how their hardware responds to the toughest conditions. If there’s a way to break a given component, racers will find it, and this phenomenon plays out across all niches of motorsport. Le Mans and other high-profile endurance races may enjoy the limelight of OEM involvement, but domestic brands remain closely tied to grassroots drag racing.

So when legendary drag racer Don Bowles, Sr. decided to come out of retirement and return to the strip, he leveraged Ford’s tight involvement with the straight-line scene. Bowles, Sr. was looking for a new engine program to replace the relatively small-displacement, Modular platform. Which, in turn, led him to Les Ryder. “They actually came on a fact-finding mission,” explained Ryder. “They’d heard we were doing a new, larger-displacement V-8 and they wanted to know what it was, and so we had a discussion.”

“The coolest thing was meeting in Les’ office,” Don Bowles, Jr. remembers. Ryder worked inside the hallowed halls of Ford’s Engineering Labs, a few doors away from Henry Ford’s original office. The Blue Oval spared no expense when constructing these offices in 1924. The exterior walls were built from Indiana limestone, and the executive halls were lined with marble and framed by mahogany walls soaring into a white ceiling. Everything was designed to be fit for automotive royalty, down to ornate light fixtures rained a soft, warm glow onto the hardwood. Mahogany Row, as it was nicknamed, housed Ford’s braintrust of engineering departments.

“It was old-school—you walk in this place and you can smell history … you can just smell it,” says Don, Jr., reliving that first meeting, back in 2005. Ryder and Don, Sr. decided that Ryder would provide prototype parts in exchange for extensive data and feedback and began discussing the Triple Seven’s defining goals: 7000 rpm, 700 hp, and 7 liters. Ryder was interested in pushing the new, big-displacement architecture of the Boss. Its 115-mm (4.52-inch) bore spacing was the Boss’s biggest advantage over the aging Modular V-8s, which measured just 100-mm (3.93-inch). This allowed the Boss to use larger pistons and valves.

Leveraging Ryders’ prototyping resources at the Ford Engineering Labs, a custom block was poured with modified cooling jackets to allow engineers to safely bore out the cylinders for 4.125-inch slugs. A custom forged crankshaft increased stroke to 4 inches, about a quarter-inch more than the production-spec crank. This would give the team the magical 427 cu-in (7-liter) figure, and when combined with the overhead-cam valvetrain, would hopefully give the Triple Seven enough airflow to meet Ford’s rpm and horsepower goals.

This is when Jack Roush’s team stepped onto the scene. Roush Performance facilitated both R&D and final assembly as it sorted out the combo together with Ford. The elder Bowles and Jack Roush proved fast friends—the kind that swapped camshafts instead of gifts at Christmas.

“Jack would fly down and the family had come down and spend time with us, Jack’s wife and mom, and then us kids would spend time together, and then Jack and Dad would be down there on the dyno over New Years’, or Easter, whenever!” Don Jr. says. “It was just crazy. I’ve seen Jack bringing an armful of camshafts while Dad would have five carburetors in there, and they would just beat that Super Stock combo just to death on the dyno. They might find 20 horsepower off the dyno, take it to the race track, and it was a tenth-and-a-half slower!”

Mahogany Row’s secret

Before the Triple Seven ever roared in anger down the strip, it was wrung out on a Spintron machine by father-son team Bob and Dennis Corn at Roush to sort out any weaknesses with the increased rpm. The stroker rotating assembly held up well, but Roush’s team needed to fine-tune the valvetrain and camshaft combination to handle the stress. Custom camshafts were made and the valvetrain was modified for mechanical lash adjustment between the rocker arm and valve. However, Roush discovered that either the heads of the valves would mushroom and cause clearance issues or the valves themselves would overheat—to the point of discoloration. Don, Sr. describes it like this: “It was amazing how hot those valves and valve springs would get when you take it [to] another 400 rpm, or add a little more lift—just trying to get the ultimate camshaft and valvetrain. And we even had oilers spraying all of the springs, just like the NASCAR motors.”

Roush added bronze valve guides and, which helped absorb heat out of the valve stem to protect it from overheating. Other than the one-off water jackets to accommodate larger ports, the Triple Seven’s cylinder heads retained the Boss production geometry for everything else in the valvetrain, accommodating the modified camshaft, aftermarket valves, and mechanical adjustment. The biggest departure from the production engines came in the induction system, which housed a Kinsler individual throttle-body setup in a massive plenum box. Lastly, the Triple Seven’s compression ratio was bumped to 12.5:1 in order to take advantage of the high-octane rating of E85, a considerable increase over the street-going version’s 9.8:1.

With each improvement, Roush’s team and Don, Sr. discovered more and more of the Triple Seven‘s potential. The modified truck engine was now singing at 9000 rpm like a NASCAR Cup motor, and as the dyno sheets kept coming back, it became increasingly clear that Ford, Roush, and Bowles, Sr. had all underestimated the Boss platform’s potential. With the valvetrain under control, the Boss surpassed the 700-hp benchmark at a measly 7000 rpm, and output cleared 800 hp as revs rose beyond 8000 rpm. By the spring of 2006, Ford, Roush, and Don knew they had an 850-hp firecracker in their hands and began preparing a new chassis for NMRA Open Comp.

“Coal Digger VI” started life as a 2005 Ford Mustang, built out with a Roush Stage 3 aero kit and carbon-fiber fenders. In name and livery, the Mustang carried on the proud lineage of yellow-clad race cars from Don Bowles, Sr., who oversaw coal mines when he wasn’t moonlighting as a mad scientist. Bowles, Sr.’s team tossed out the back half of the S197 chassis in favor of a stout four-link suspension and replaced the Mustang’s original five-speed Tremec TR-3650 with a sequentially-shifted G-Force GF-5R gearbox. With the new chassis tubing, including the roll cage, Coal Digger VI tipped the scales around 3500 pounds in Open Comp trim.

Because the engine wasn’t approved for production use and the team kept the exact details of Triple Seven under a need-to-know policy, Don Sr.’s team preferred Open Comp’s more flexible rulebook and “run what you brung” approach. Open Comp allowed the team to gather the track-side data it needed in the demanding context of bracket racing, in which drivers “dial in” the elapsed time (ET) they expect to hit. A driver’s goal is to get as close as possible to the dial-in ET while not “breaking out” and beating the dial-in time. The setup rewards the most consistent performer, rather than leaving the results up to an outright assault on the finish line. Bracket racing was an excellent way to test the Triple Seven’s durability and consistency, and so the team began testing at Michigan’s Milan Dragway before entering NMRA Open Comp in 2006.

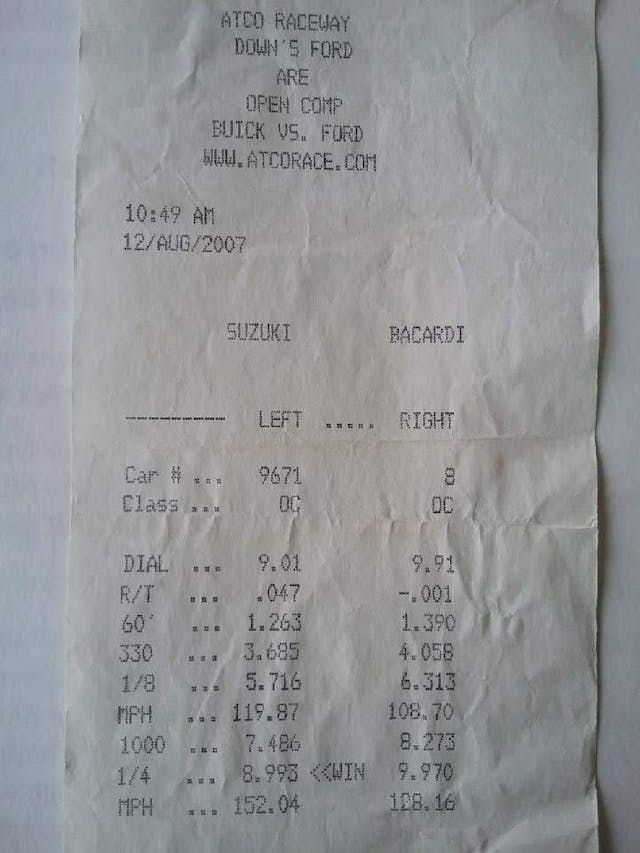

Much to the satisfaction of the Blue Oval contingency, the Triple Seven proved it was no mere dyno queen. It knocked down the 9-second ladder, eventually running consistently in the 9.0-second range. Better yet, it would break the 8-second barrier months later at New Jersey’s Atco Dragway. “We run low 9s—of course, if you went quicker than a 9.0 you broke out of the class,” Don, Sr. recalls. “But the other guy red-lit on the first round and I stayed on it to get that 8-second run!” He credits the better air density at Atco’s lower elevation. In any case, the 8.993-second pass demonstrated that the Triple Seven was a serious contender as a performance car engine—a status made even stronger by its 152-mph trap speed recorded that same day. “Wasn’t too bad of speed either, for that heavy of a car,” Don, Sr. modestly exclaims. The dead-nuts reliable Triple Seven was able to finish the 2007 NMRA season second in points with three event wins at the hands of Don, Sr.

The great what-if

Sadly, at the end of the season, the Triple Seven was pulled and replaced by an ex-NASCAR Ford D3 mill, which produced nearly the same horsepower and rpm but was available in surplus while the Cup Car engines changed generations. It was a sensible move on the part of Don Bowles Racing as the Triple Seven’s development wound down; the prototype engine was the only one in existence. (The production, 6.2-liter variant found in the Raptor would not debut for several more years.) Les Ryder had since retired from Ford, though he rejoined the Triple Seven project during a short development stint at Roush. Ultimately, and for its own reasons, Ford decided not to evolve the Boss 6.2-liter platform for the road-going Mustang. The Coyote was in development by then, and the Coyote’s potential for better fuel economy likely solidified its business case following the 2008 economic collapse.

The Mustang wasn’t the only model that stood to benefit from the 6.2-liter mill. Ford had intentions to produce several variations of the Boss architecture; the overhead-cam configuration of the Boss allowed for cost-effective iterations with three- or four-valve configurations, just like the smaller Modular V-8s. “We originally started with an aluminum-block alternative for lighter-weight, passenger-car applications that got dropped along the way,” Ryder mentions. Ford had even considered a diesel surrogate of sorts—a specialized four-valve variant that could match the Powerstroke’s torque figures without falling under the incredibly stringent diesel emission regulations proposed at the time.

The Coyote was a much-needed injection of horsepower into the Mustang, a game that it had been losing to General Motors for decades. Despite its Narcan-like effect on the Mustang, however, the Coyote’s 100-mm bore spacing subjects it to similar displacement limitations as the retired Modular motors. What if the Mustang had packed a milder version of Triple Seven, even at the Raptor’s 6.2-liter displacement? True, the original 6.2-liter mill was heavily focused on low-end torque, but with a few minor changes—like an intake and a set of camshafts—the Boss’s performance potential was clearly there. Today’s high-horsepower pony cars may compensate for displacement with boost, but there will never be anything quite like the brute-force response of a big-inch, naturally-aspirated engine—especially for power-hungry drag racers. Could the Triple-Seven ever return for production? Almost certainly not. Do we wish it could? You know the answer to that question …

It’s actually a 2006

So proud of my Uncle Don. RIP