The History of Black Drag Racers in Chicago Runs Deep

Most forms of auto racing have seen only limited participation from Black Americans. Drag racing in my hometown of Chicago, on the other hand, is a whole different story. The toddlin’ town has bred many Black racers who competed on both strip and street. Black History Month is a good time to share fascinating chapters of this history, especially those that people still living today can recall.

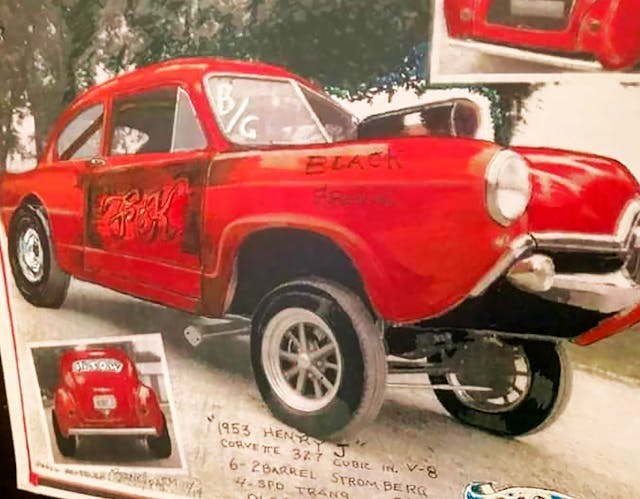

Raylo Riley, a successful Black drag racer and the unofficial historian of the Chicago scene, speaks with reverence about the early days. “Frank King was among the first black drag racers that I know of,” Riley told Hagerty. “In 1962, King’s Chevy-powered Henry J was the car to beat at street races late at night. So when a race promotor named Bill Schade organized an indoor drag race at Chicago’s International Amphitheater, Frank was there. Clyde Hopper was there too. He was a Black drag racer who ran some badass Mopars on the street and at the track. I’m not sure if there were other Black racers at the Amphitheater drags,” Riley continued, “but Messino might know.”

Dick Messino is an octogenarian Chicago drag racer who was featured on the Hagerty site last year. He’s a white guy who did business with Black drag racers for many years and has a near-photographic memory. He told me that Hopper and King weren’t the only Black racers at that first indoor drag event. “There were at least half a dozen Black guys,” Messino said, “and most of them were fast and making big-dollar side bets.” According to Messino, Hopper died in a long-ago street race on South Chicago Avenue—a lightly traveled artery that was the scene of many races back in the day.

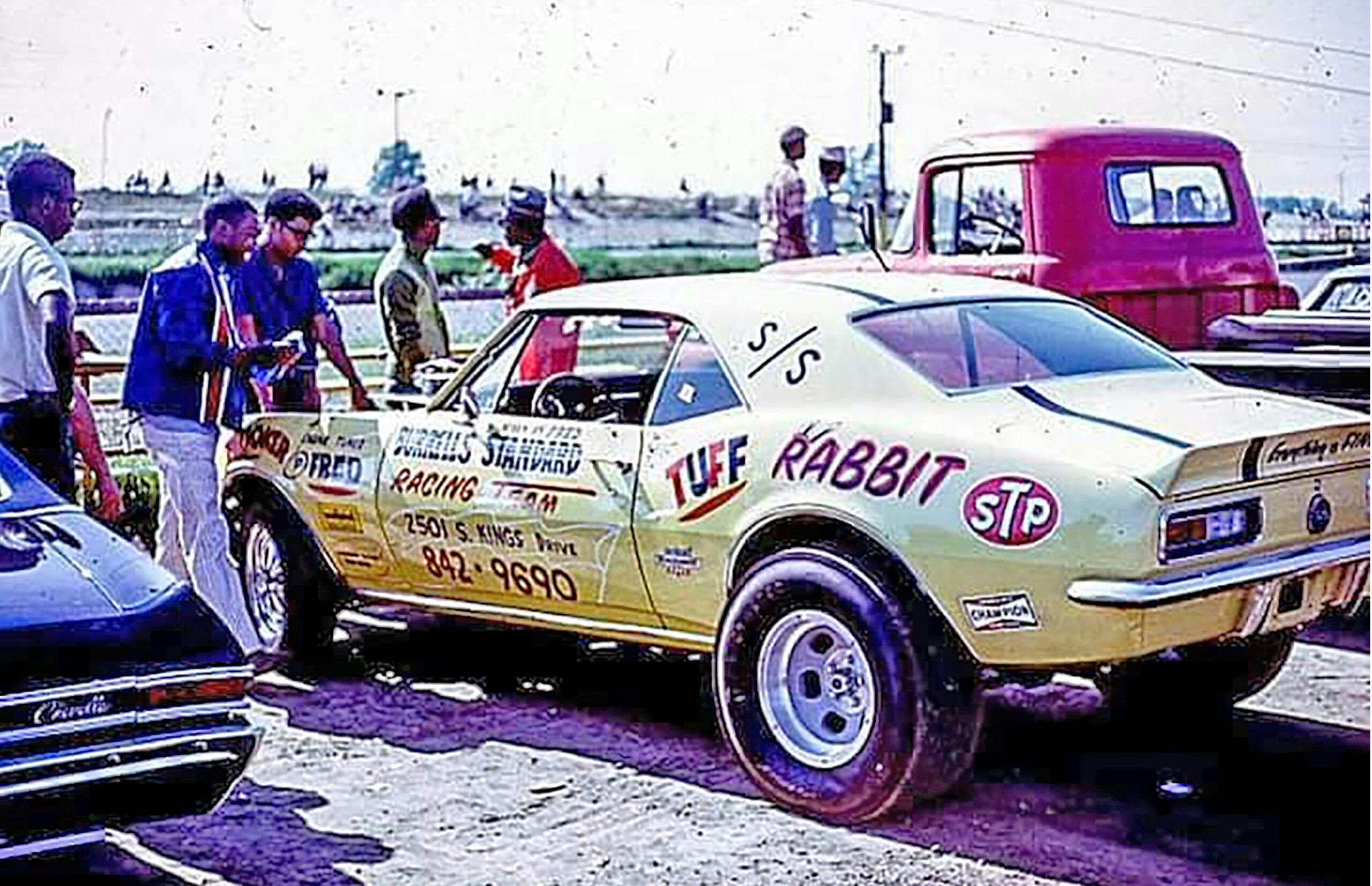

Messino recalls another successful Black racer known to him simply as “John Junior.” In the late ’60s, Junior put together a ’67 Camaro race car with an engine from Simonsen’s Auto Parts, a speed shop on the South Side that built motors for pro drag racers. The Camaro sported a 427 Chevy with high-compression pistons, a racing camshaft, and other goodies, all backed by a Clutchflite transmission—a then-popular mating of a Chrysler TorqueFlite and manual clutch.

“Junior raced a moonlighting pro drag racer on Interstate 57 for $1000,” Messino recalled. “The highway had been completed but wasn’t open to traffic. Hundreds of people lined the sides of 57 to watch the race, which Junior and his Camaro won going away.”

Another early hotspot of street racing where Black racers were the majority was a McDonald’s restaurant on the South Side’s 71st Street. Messino recalls that dozens of Black racers would gather there every weekend night. “White or Black, you could count on getting a race there,” Messino said. “There were very few posers.”

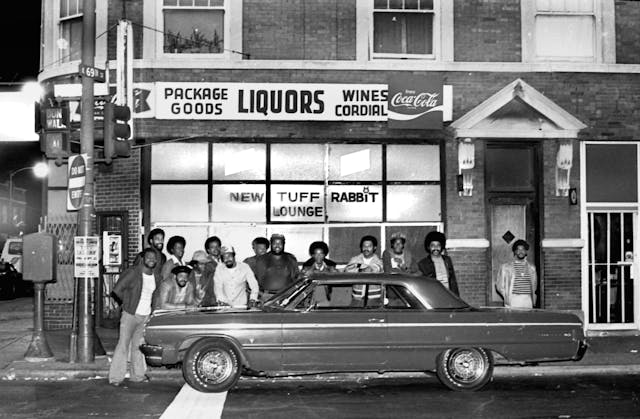

Not far from there, on 69th and State Street, was Sammy Scott’s New Tuff Rabbit Lounge. Scott was partners with a drag racer of renown named Ed Burrell. They campaigned a series of potent cars that wore the Tuff Rabbit name and were the pride of the community, dominating their class at local tracks. Scott’s bar was a busy watering hole where many drivers hung out, but it’s best remembered as the focal point of some of the most outrageous and dangerous racing ever to take place on Chicago streets: the flying mile.

I heard about the flying mile from pro drag racer Austin Coil and his pal, Merle Mangels, in the mid ’70s. They built motors for some of the Black racers who pursued this extreme, illegal sport. When I asked how I could learn more and maybe photograph the races, they sent me to the Tuff Rabbit and told me to ask for the Rabbit. That would be Bobby “Rabbit” Parker. Coil and Mangels had built a 500-horsepower small-block for Parker’s Corvette. They were among only a few people other than the racers who knew that, late at night, when there was virtually no traffic on the Chicago Skyway Toll Bridge, very hot street machines would race for a full mile from a rolling start.

I made my way to the Tuff Rabbit one summer night, armed with a camera and hoping to get a story about the mile-long drags for High Performance CARS, the only magazine of the day that was either foolish enough or courageous enough to cover street racing. When I walked through the bar’s front door, many eyes found me and conversations turned muted.

That initial quiet quickly broke: “It’s that magazine guy,” said a friendly voice from the back of the bar, which I would later learn belonged to Harry “Dawg” Cannon, buddy to Parker who was seated at a table wearing a Blue Max hat and a diamond-studded rabbit pendant. Cannon wore an Orange County International Raceway jacket with a Black American Racers Association patch. Next to him was a huge man named Big Fred, invoking images of Bad Leroy Brown. Years later, I learned that Dawg, Rabbit, and Fred were highly successful drag racers at local tracks but were best known for their street racing exploits.

“We’re gonna show you how mile racing goes down,” said Big Fred. “Frog here will drive you up to the starting line.”

Ronald “Frog” Williams and I followed Parker, Cannon, and Fred onto the seven-mile-long Chicago Skyway. There, high above the city streets, two Corvettes with loud, loping exhaust and fat tires left the starting line just north of the 87th Street toll booth, racing pedal to the metal for a full mile, braking only at a finish line about half a mile before the State Street exit, which was just a few blocks south of the Tuff Rabbit Lounge. The Skyway wasn’t smooth, and at high speed the cars bounced violently—a frightening scenario I witnessed while clinging perilously to the side of the bridge.

Such craziness is part of the city’s past, although I hear it still happens occasionally despite the danger and illegality. I do not endorse such activity, though the guys who raised hell 50 years ago helped build a movement that ultimately inspired many Black Chicagoans to formally compete at nearby dragstrips. First, it was at US 30 in Gary, Indiana, which closed in the ’80s, and today at multiple tracks in the Midwest, including US 41 Motorplex in Morocco, Indiana; US 131 Motorsports Park in Martin, Michigan; Byron Dragway in Byron, Illinois; Great Lakes Dragaway in Union Grove, Wisconsin; and Cordova Dragway in Cordova, Illinois.

Raylo Riley, who told me about some of the first Black drag racers in Chicago, has raced at every one of those tracks. He is, however, best known as the online historian and #1 fan of Gary’s US 30 drag strip. “I try to keep the memory of US 30 alive,“ said Riley. “I organize reunions, post about the old track regularly, and sell US 30 T-shirts that feature some of the stars of that great old track.”

Riley is also a successful bracket racer. He tours nationally with his ’95 Camaro. It’s a full-tilt race car with a 421-cubic-inch small-block Chevy under the hood, a roll cage, and a complement of top-shelf racing components. He runs only bracket races with big-dollar payouts and has won $10,000 twice at national bracket-racing events. In the quarter-mile he runs 10.20 at more than 125 mph; in the 1/8th mile, the track length at which almost all bracket racing is contested, his car covers the distance in 6.40 seconds. Consistency, a product of both car preparation and driver skill, is key to success at bracket racing, where each racer dials in their projected elapsed time and the start is staggered to reflect those numbers. Get to the other end too soon or too late, and you lose.

Drag racing is a family thing for the Rileys. “My father, Edward Riley, started racing at U.S. 30 more than 50 years ago,” said Riley. “I remember he bought a new ’70 Camaro and was taking it to the track before the little rubber dingles had worn off the tires. He was very successful running ET 5 at U.S. 30, a class for cars running in the 11s, much faster than the muscle cars of the day.”

Raylo’s brother Kyle was successful in racing, both in the highly competitive NHRA Stock Eliminator class and as a bracket racer. Today, his SFG Promotions is prominent in the sport. SFG paid a record $1.1 million to the winner of a July 2023 bracket race at US 131 Motorsports Park. That’s far more than Top Fuel and Funny Car winners were awarded at the recent PRO race in Bradenton, Florida, billed as the richest race in drag racing history. I’m comparing apples to oranges here, but Kyle Riley’s achievements with SFG Promotions are beyond impressive.

Raylo Riley introduced me to Richard Davis, known to his compatriots as “Big Drag.” Davis has been drag racing since 1976. Among his stable of nice machines are a Jerry Bickel Camaro that he runs in Pro Mod, a ’63 Split-Window Corvette that is primarily a street-race machine, a ’57 Chevy wagon that can easily lift the front wheels at launch, and several others. He got the drag racing bug from his dad, a Mopar guy who hung around Grand Spaulding Dodge back in the Gary Dyer/Mr. Norm days. He grew up loving Mopars but switched to Chevys for the availability and ready access to tuning information.

In the 1970s, Davis was one of Chicago’s most successful street racers. Parker, aka Rabbit, put him in his first car and taught him to shift a four-speed. “Rabbit had a brother that we called CW—his real name was Charlie Wilson,” said Davis. “He had a black Chevelle called ‘Bullet’ that won a lot of races, a Pontiac called ‘The Judge’, and a ’66 Chevelle called ‘Do It Any Way You Want’.” He got in trouble and died young. Rabbit died young, too.”

Both Davis and Riley remember a guy I knew well: Freddy Kemp, a Black drag racer who was paralyzed from the waist down. He got around on crutches and was razor-sharp, kind, and gentle. He owned a potent Dodge called “Breaking Point.” He had outfitted it with home-built hand controls for braking and throttle and competed successfully at local dragstrips.

In the late ’70s, I was teaching high school English and sponsored an auto shop club on the side. The students and I were building a dragster that we planned to race locally. Kemp would come by from time to time to lend a hand. I left for a New York journalism job in March 1980 and lost track of Kemp. Davis told me Freddy was allegedly killed by police in some kind of altercation long ago. I have no way of verifying that, but I’m dumbstruck.

Today, Davis, who is now 61, organizes races, including events that are known as gambler races: Entrants buy their way in and the lion’s share of the pot goes to the winner. Davis says he takes nothing but just wants the guys to have a good time and make some money. He also sponsors grudge races, which are essentially street races at the track. In those, competitors arrange private bets (my car vs. yours) frequently for big money. The “Christmas tree,” or electronic starting system, makes everything fair and square. With an electronic start, a car can be given a handicap by staging the slower car on the rear tire rather than the front. Thus it begins the race almost a full car length in front of its competition. It’s much more accurate than trying to stage such a competition on the street.

“Who are the best of Chicago’s Black racers today?” I asked Davis.

“That depends if you’re talking South Side or West Side,” he said. “On the South Side, you got Forgiato Zae. He does all the wrench work on his car and builds his own engines. His uncle was a street racing legend known as Starchild Mike. Another guy called Von is darn good. On the West Side, you got a young guy named Petey, and a racer they call Peanut is up and coming.

In all, there are hundreds of fast racers in the parts of town where most of the people who look like me live. It’s a good time to be a Black drag racer in Chicago.”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

LA had a lot of black serious street racers too in the 70’s. These guys were fast.

Big Willy Robertson and “Fast & Fourty” Rodney Flournoy

What a great article – I used to live in Chicago and didn’t know any of this. The first picture of the C2 and C3 on the bridge is so evocative of those times. one of the best articles I have read!

This is a great history and invokes how racers just know the car, and they know it’s fast. And the many great articles written on Haggerty and elsewhere about the “Black Ghost” Godfrey Qualls Detroit traffic cop by day and a street racing a ‘70 Challenger by night.

In the late 80s there was a lot of raving that included Black guys on Archer. Some were using hyped Grand Nationals.

I am still confused as to why certain races need to be capitalized and others do not. On a personal note, I have drag racing friends of various racial backgrounds who all get along just fine. But, I will try not to inject common sense into this.

Some publcations, including The New York Times, a newspaper that has published much of my writing, decided that “Black”!should be capitalized a few years ago.. It’s mainly a matter of editorial style, rather than a social or political issue.

Editorial style or not, it is improper English. There was a time not so long ago when one would be very surprised to see a mistake in publishing.

There was a also a time not long ago when there was no method for people to quickly spout off whatever dumb thought they had on most every piece of publishing they saw. Maybe we should go back to those times.

What do you imagine the editorial style is guided by, if not politics?

Did everyone who promoted the myth of the Black Ghost Challenger get a cut of the amount the mark was soaked for at auction?

I agree. If you’re going to capitalize black, then you need the same with white. This is just the thing that causes division in this country! I know it sounds petty, but that’s the truth!

Those Corvette’s at the top look good. I remember the street racing scene in Chicagoland in the late 90’s through 2000’s. That was a pretty cool time for all.

Just a note, in picture #4 and #17, the Camaros are both 1967 model years. Not 1968. Notice the vent windows and no fender side markers.

Great story and very interesting!

Lest we not forget the great Fred Stone and Leonard Woods with their Supercharged Olds-powered ’41 Willys Coupe, driven by the diminutive Doug “Cookie” Cook. One of my all-time favorite racing teams.

Cool story about a great bunch of gearheads from Chicago, of all places. Who knew?

Merle Mangles was a legit old school guy.RIP.

In 1969 my friend Dale Ford drove up to high school in a new 1969 Chevelle SS 396-375 hp solid lifter motor.

Bench seat M-22 4 sp. Nile green, white interior the best looking Chevelle I had ever seen.

Race was never an issue, Dale was just another gear head like rest of us at that time.

I remember he named the car Bad News. He put a 4.88 rear end in it. Needless to say he won a lot of racers with his skill and that 4.88. On the downside I think he went through 7 engines.

Excellent article great pics some great autos and car people….

I grew up on the northwest side of Chicago and my dad told me about racing at the incinerators if I remember were off of Clayborn. We did a lot of street racing in the early 70s and when your girl friends dad is a Chicago policeman and you got stopped you were always told to just go home. Skips drive inn was another famous place to race. I had a lot of great times back then.

Halsted and Evergreen

Damen and Fulton was the bestspot