Etienne Butterlin’s hyper-realistic hot rods dazzle in paint and ink

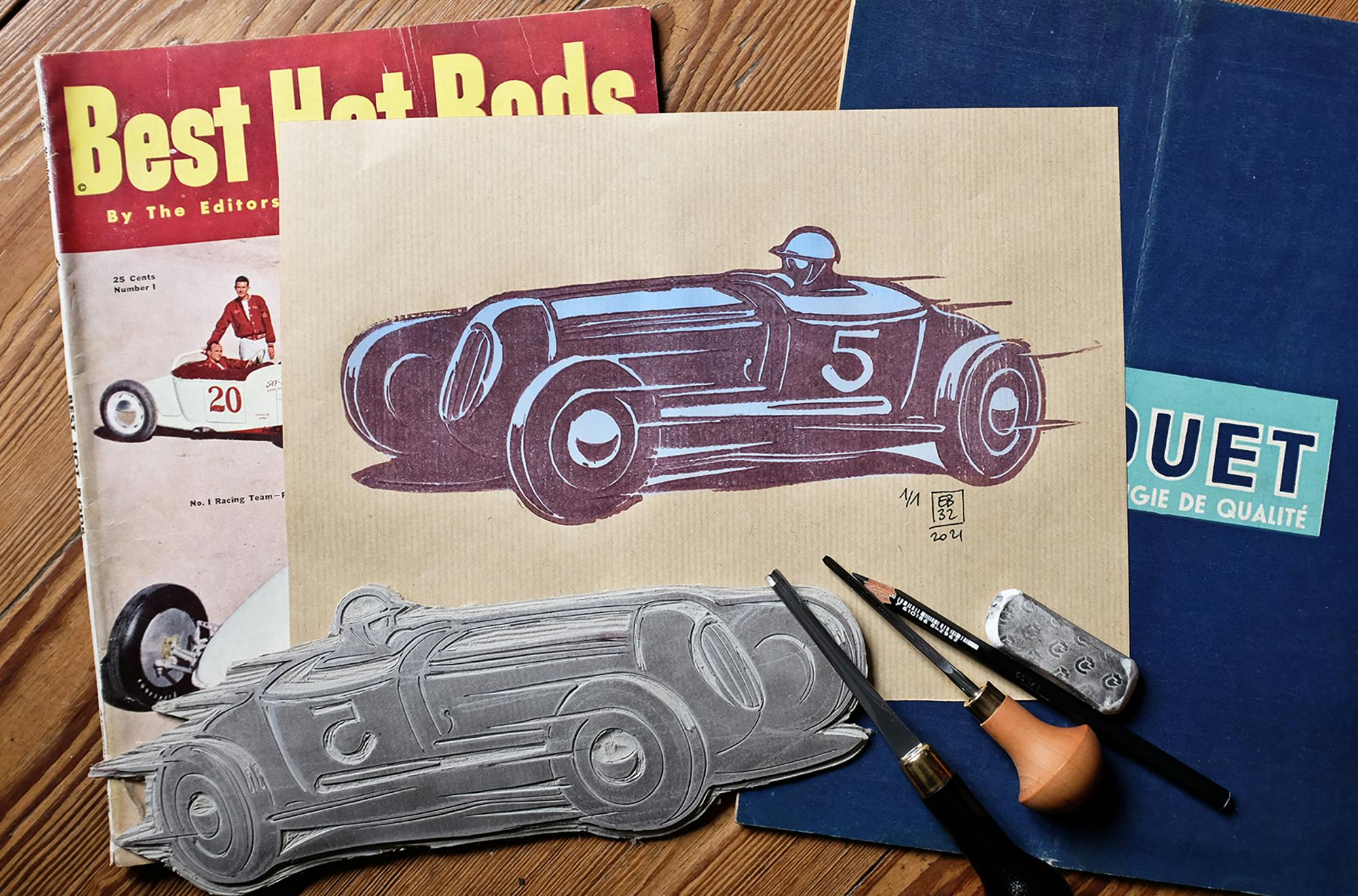

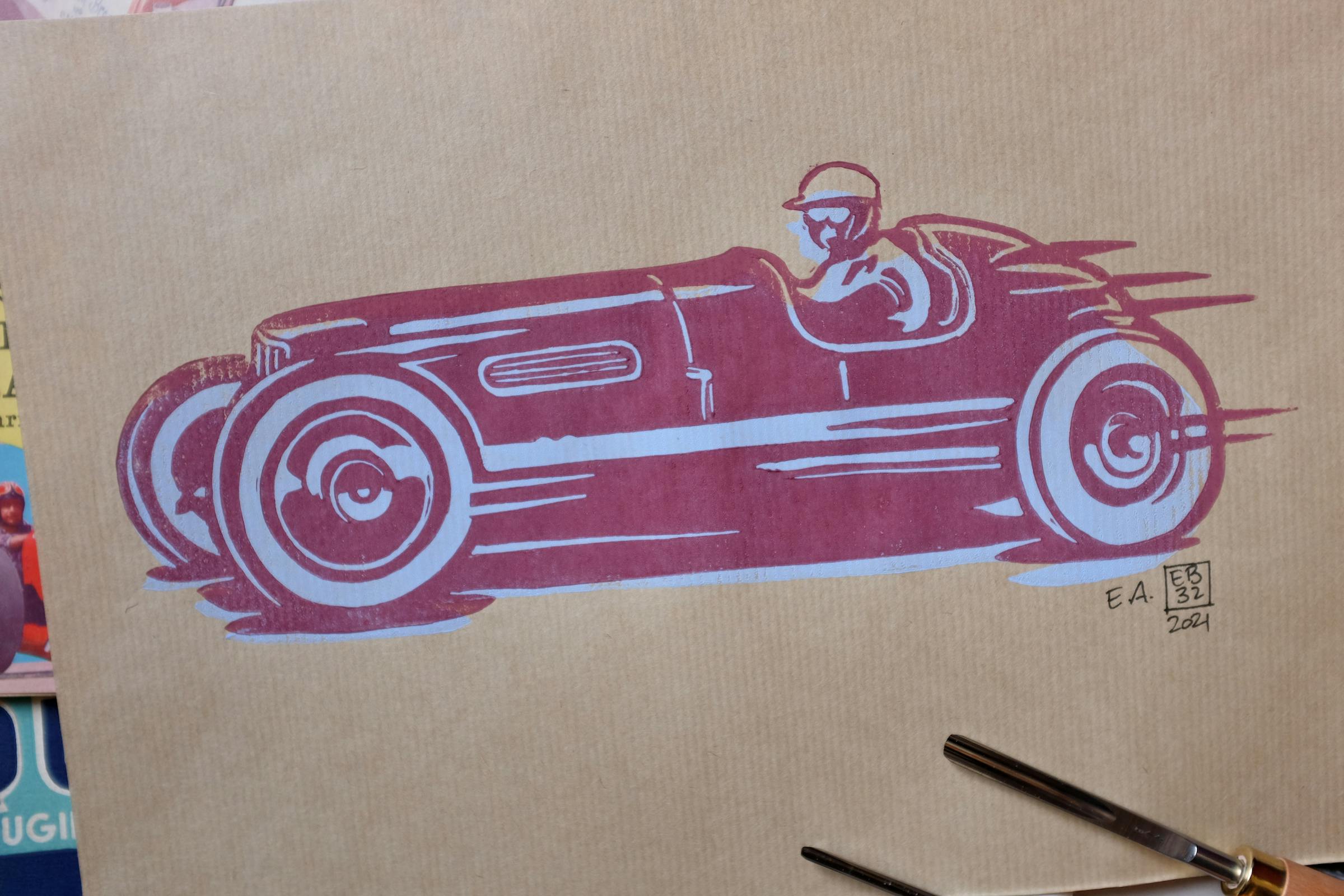

Thinking in reverse; it’s a particular kind of logic that painter and lately-turned linocut printer Etienne Butterlin performs when conjuring up a new hot rod linocut design. Rendered in dark plum, deep red, and moody blue inks on brown paper made from wood pulp, they are striking, dynamic, and hand-pressed in limited runs.

To begin the process, Butterlin sketches a heavily simplified line drawing of the vehicle he wishes to depict. In contrast to the super-realist approach he applies when creating one of his acrylic on canvas automotive paintings, keeping the linocut form free from fussy details is key to success. It’s at this stage of composition that the backwards “brain gymnastics” commence, because Butterlin has to decide which parts of the car need to be carved out of the lino block. Once he’s committed to it with a gouge, there’s no going back.

“Everything I remove will be the color of the paper, and what remains of the lino will be inked and printed,” explains Butterlin, who must flip the image before transferring it on to the lino plate to ensure the finished print appears the same way around as his original drawing. Then, allowing elements of the design to evolve organically as he etches, Butterlin relaxes into the more organic and experimental act of engraving.

Bold and directional “speed lines” bring prints, such as his one of the iconic Pierson Brothers’ 1934 Ford coupe to life. With details such as tire tread omitted, other striking features of the car—most notably its sweeping laid-back windshield—are given permission to stand out.

Reminiscent of Gus Maanum’s ink drawings (a post-war artist who made his name in America producing illustrations of competitors’ hot rods for inclusion in souvenir racing programes and booklets) Butterlin’s prints are stylized to reflect the automotive artwork that emerged during the early days of land speed racing.

“Hot rodding had already started to grow before World War II, but the post-war era offered an incredible space for the development of this phenomenon,” explains Butterlin, who lives in France. “It was such an exciting period, there was so much creativity and empirical intelligence, everything seemed possible.”

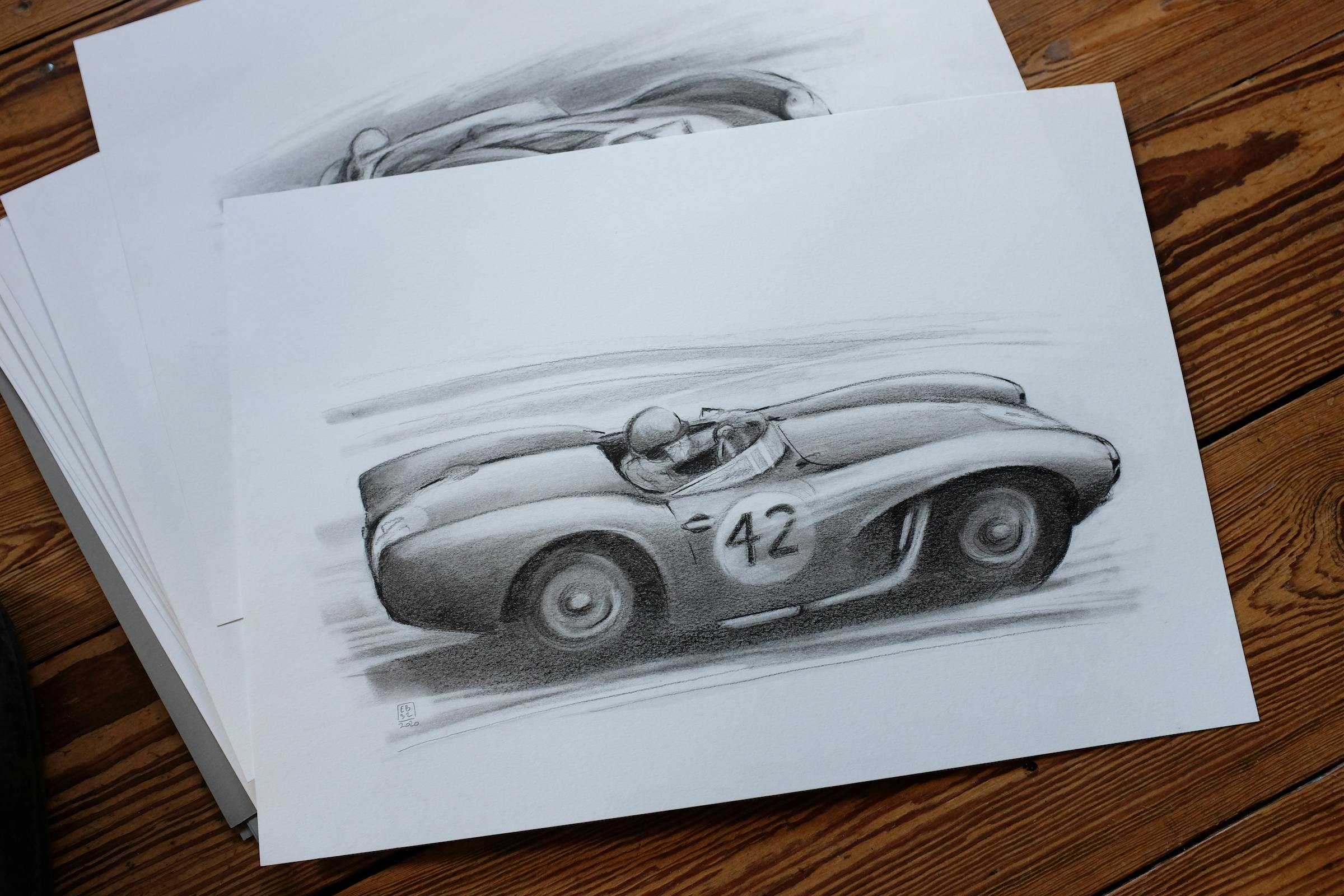

It’s still in its infancy, but Butterlin hopes his linocut series will allow people to access his art at a more affordable price point. It’s his astonishingly realistic acrylic paintings (and charcoal drawings), however, that he is best known for at present.

Focusing predominantly, but not exclusively, on “poor boy vintage race cars” (that’s hot rods from the Forties and Fifties to you and me) Butterlin’s pieces have featured some of his favorite customized and classic car rides. There’s the Rolling Bones 232B, the Rolling Bones Hot Rod Shop’s famous 1929 Ford Model A—which had a starring role at the 2021 Goodwood Revival, and a vehicle which Butterlin had ridden shotgun with its owner on a 3100 mile pilgrimage across the USA—as well as the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union Silver Arrows.

Each is a demonstration of Butterlin’s incredible trompe l’oeil technical ability, and he’s open to commissions that will allow him to expand his repertoire. But it’s his painting of the “Monkey Pecker,” a 1934 Ford coupe built by the famous Texan hot rodder Brian Bass, that puts a twinkle in his eye: “The metallic blue color was a challenge, and I think I succeeded in recreating it.”

At home in his dedicated studio-cum-office and library, Butterlin likes to paint and print to the rhythm of jazz, blues, Fifties Rockabilly or Western Swing, but he doesn’t find comfort in the familiar. Artistic technique, he believes, should evolve in response to the challenges that depicting different subjects presents.

“At the beginning, my paintings were darker, probably because I’m a fan of Renaissance painting, and chiaroscuro,” says Butterlin, whose apartment lies 18 miles from the Bugatti town, Molsheim. “I’m trying to bring more luminosity and complex lights into my paintings. My style has really evolved since working on a salt lake series a few months ago, but there is still a long way to go to get to where I want to be.”

Working from photographs, and often returning to images many years after he first captured them, Butterlin frequently combines several images that he has taken using Photoshop to compose the scene he has in mind.

“Sometimes I add what is missing, such as drivers and a background,” he says. “The photo is a starting point, on which I can rely, but from which I must escape. Once it is composed, I transfer it on the canvas, and start to paint. When the image is a composition from several photos, the light and the atmosphere is created while painting, as well as the speed effects.”

Butterlin hasn’t always lived for, nor tried to earn a living from, his automotive art. This journey began in 2019 when his ten-year tenure as editor-in-chief at the French hot rod and custom magazine, PowerGlide, came to an end in his mid-forties—an age he feels is particularly challenging in which to make a career change. It’s not been an “easy adventure” but with a degree from the Strasbourg School of Decorative Arts behind him, and years of experience working as a photographer and graphic designer, Butterlin channelled the same give-it-a-go attitude that compelled him to start drawing cars at the age of 14.

“In my teens, I fell in love with everything about the ’40s and ’50s and started to buy vintage and American car magazines. In a 1989 issue of the French magazine NITRO, there was an incredible article about the English Low-Flyers car club and the traditional ’40s hot rods they drove. It included a series of pictures that were shot at an airfield in the U.K.”

At this time, Butterlin feels, the hot rod scene was dominated by “’90s street rod crap,” which he says was characterized by garishly colored cars, digital dashboards, and billet aluminum wheels. “Seeing these guys with flat black flathead powered cars, low key in-progress hot rods, and wearing WWII jackets was a true revelation for me; I discovered the ’40s roots of hot rodding.”

Convincingly, Butterlin insists the act of building his own hot rods helps him to “paint them more easily”, and as he settles down to work on his current restoration project: a 1929 Ford roadster powered by a flathead V-8 that he keeps in a rented barn beside his Chevrolet-powered modified roadster. “I love the creativity that hot rodding offers,” he says, assuming a comfortable demeanor. “It’s a restoration job, like for any old car, but it leaves much more freedom and creativity.”

Whether it’s with a wrench, a paint brush, or a gouge, Butterlin will always find a way to channel his passion for these hopped-up ’n’ stripped-down cars.