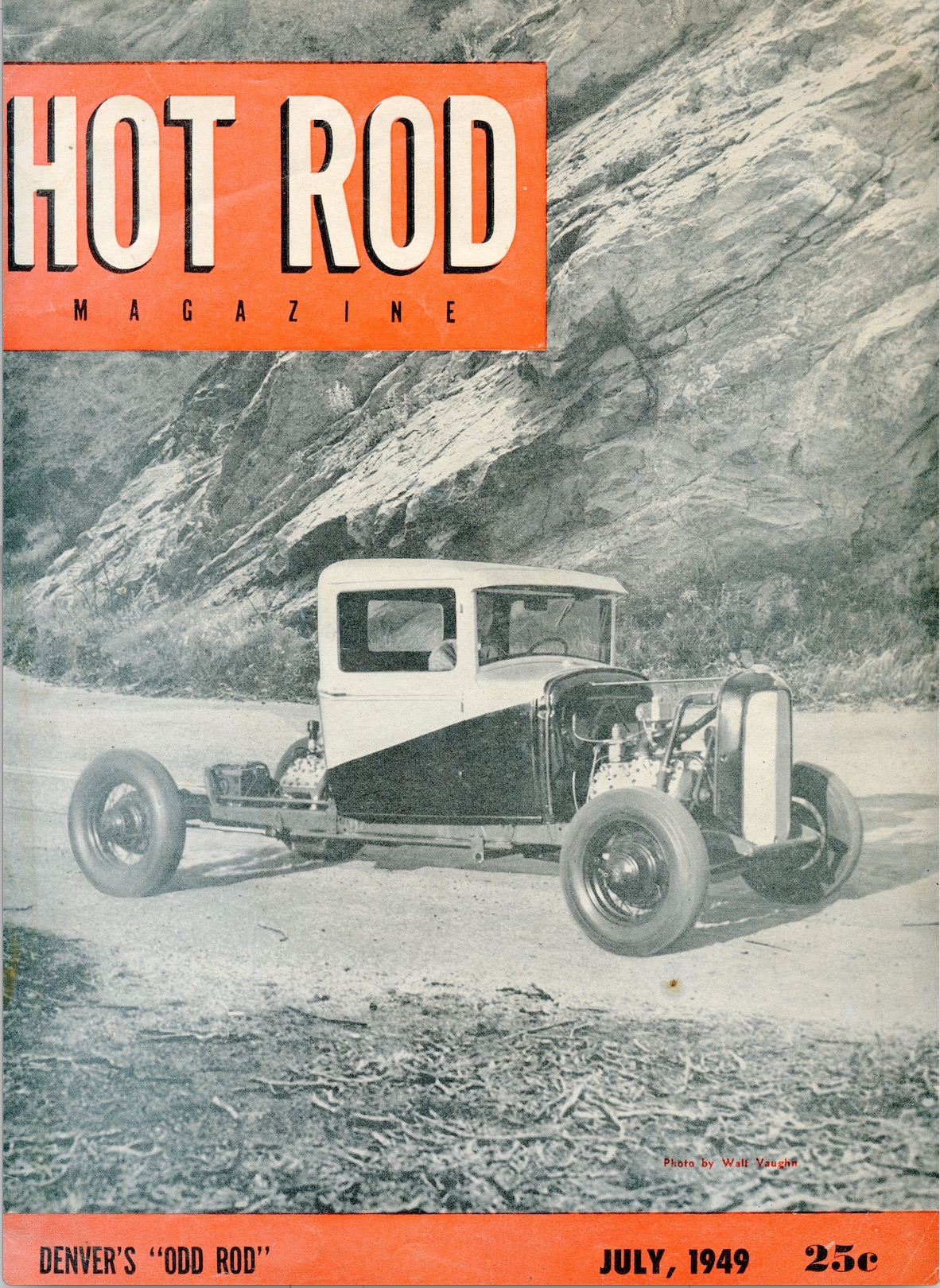

The odd trail of the hot-rodding Odd Rod

Another day, another re-creation of one of the cars plastered across the cover of a mid-century Hot Rod Magazine. Or so it seems for Mike “Nick” Nicholas, who earlier this fall finished building a detail-oriented copy of a twin-engined dry lake speedster called “Odd Rod,” which appeared on the July 1949 cover of the publication.

This is his second such project; the first was a clone of the 1934 Chevy dragster known as T-33.

In the years after World War II, when gasoline once again became available for civilian use, hot-rodders returned to the dry lake beds of the West in pursuit of ever higher speed records. The Great Depression was finally over, and that, together with an abundance of war surplus materials and a general spirit of experimentation and discovery, made for a golden era of technological advancement.

A Denver mechanic named Bill Kenz was one of the hot-rodders caught up in the post-war racing boom. During the war, Kenz and his business partner, Roy Leslie, had a fleet maintenance contract with the military, rebuilding flathead V-8s for the soldiers keeping the world safe for democracy overseas. Inspired by the mid-engine Grand Prix cars that Auto Union engineers had built in Germany before the war, Kenz spent nights and weekends working on his own mid-engine car while the war still raged, hoping to campaign it at the Bonneville Salt Flats in the Utah high desert when things got back to normal.

“Someone told him, ‘No way you can make two engines work,’ and he said, ‘Watch me,’” Nicholas said.

Thus was spawned Odd Rod, the mutant pickup truck that went on to claim glory on the salt. It would seem equally unlikely that anyone could rebuild from scratch—using nothing but an old magazine, some pictures, scavenged parts, and interviews with old timers—a car that was, for its day, fairly complicated. But Nicholas, no stranger to historical research and painstakingly accurate reconstruction work, managed to pull off a copy that’s pretty close to perfect.

“It’s pretty much 98-percent correct,” he said, although it’s difficult to tell which two percent is amiss.

The foundation for the Odd Rod is two Model A frames welded together, with a 1931 Ford pickup body perched on top. Nicholas said the truck was originally going to be mid-engine rear-drive—with the engine where the truck’s bed once was—but when Kenz saw that there was plenty of room for another engine up front, he added a second 221-cubic-inch Ford flathead V-8, connecting it to the first mill with a custom driveshaft, as well as a homemade system for balancing the carburetors on engines sitting several feet apart. It has two clutches—one for each engine—and a standard Ford Model A axle. One radiator does double duty for both engines, which use customized Lincoln distributors and Edelbrock intakes and heads. The front engine has a Mercury carburetor there are three Stromberg 97 carbs on the rear engine.

Nicholas says the Odd Rod drives like a regular car, with a floor shifter and everything. The difference is in the two-engine setup. The rear clutch is operated by the regular clutch pedal, and is started with an electric starter. The front engine is started by engaging the front clutch, sort of like bump-starting a regular car. The result is something pretty quick for the era, Nicholas said.

“A lot of people ask why they used a pickup truck,” Nicholas said. “It was their shop truck. It’s what they had. They didn’t have money to go out and buy things, so they just made due. That’s one of the things that makes it so great, is the innovation and ingenuity.”

The car won the Lakester class at the inaugural Bonneville National Speed Trials in 1949, recording an average speed of just under 141 mph (its top speed was about 145). But Kenz and Leslie knew they’d have to up their game to compete in later trials. Over the following winter, they built a tube-framed, aluminum-bodied streamliner—the now-famous 777—in which to house the twin-engine drivetrain. In 1950, it became the first hot rod to break the 200-mph mark.

“It went 255 in ’53 using the same basic drivetrain,” Nicholas said, adding that in 1957, after the addition of a third engine and four-wheel drive, the car broke 270 mph. “There were guys coming over from Europe with airplane engines going 200, 300 mph, and Bill Kenz was just using stock Ford parts to go more than 250.”

That version of the car still exists in a museum in Denver, but its construction meant the Odd Rod was finished. After a retired machinist named Duane Helms saw a part at a swap meet that reminded him of the legendary hot rod, he set his sights upon recreating the car. Helms spent a decade collecting parts, but after a bout with colon cancer laid him low, he knew he needed to finish the project soon if he wanted to see it to completion. A couple of years ago, he approached Nicholas, who was by then already known as someone who could reconstruct ancient racing history, more or less down to the bolt.

In August, Nicholas and Helms took the Odd Rod tribute car to Bonneville, and they were the first to run on the salt ahead of time trials for the 400-mph streamliners. Nicholas said they only went about 80 mph or so, but it was a fun way to kick off the hardcore racing. And regardless of speed, they helped to complete a journey that brought the Odd Rod full circle, back to its post-war roots.