The 1968–69 MG MGC had size 3000 shoes to fill

Set your clock back to 1967 for a moment. Back when MG sports cars still roamed the earth. It was before the dark days of British Leyland, but MG was still part of the British Motor Corporation (BMC), which also owned Austin, Morris, and others. Thanks to corporate cost-cutting and U.S. safety regulations that year, MG found itself with the unenviable task of building a replacement for the revered Austin-Healey 3000. Remember, the Healey was a quintessential classic English roadster—a car almost impossible to dislike. It was a tough act to follow, and MG didn’t have a lot of resources at its disposal. Imagine showing up to an open mic night and realizing you’re up after Dave Chapelle.

MG’s answer was essentially a softer six-cylinder version of the MGB, called the MGC. Unlike the body-on-frame Healey the MGC could meet American safety rules, but it failed to live up to expectations, being neither sporty enough nor distinctive enough to make an impression. A swing and a miss, the MGC is as much a footnote in the history of the ever-popular MGB as it is a model in its own right, but for those in the know it’s an attractive, rare vintage cruiser that doesn’t break the bank.

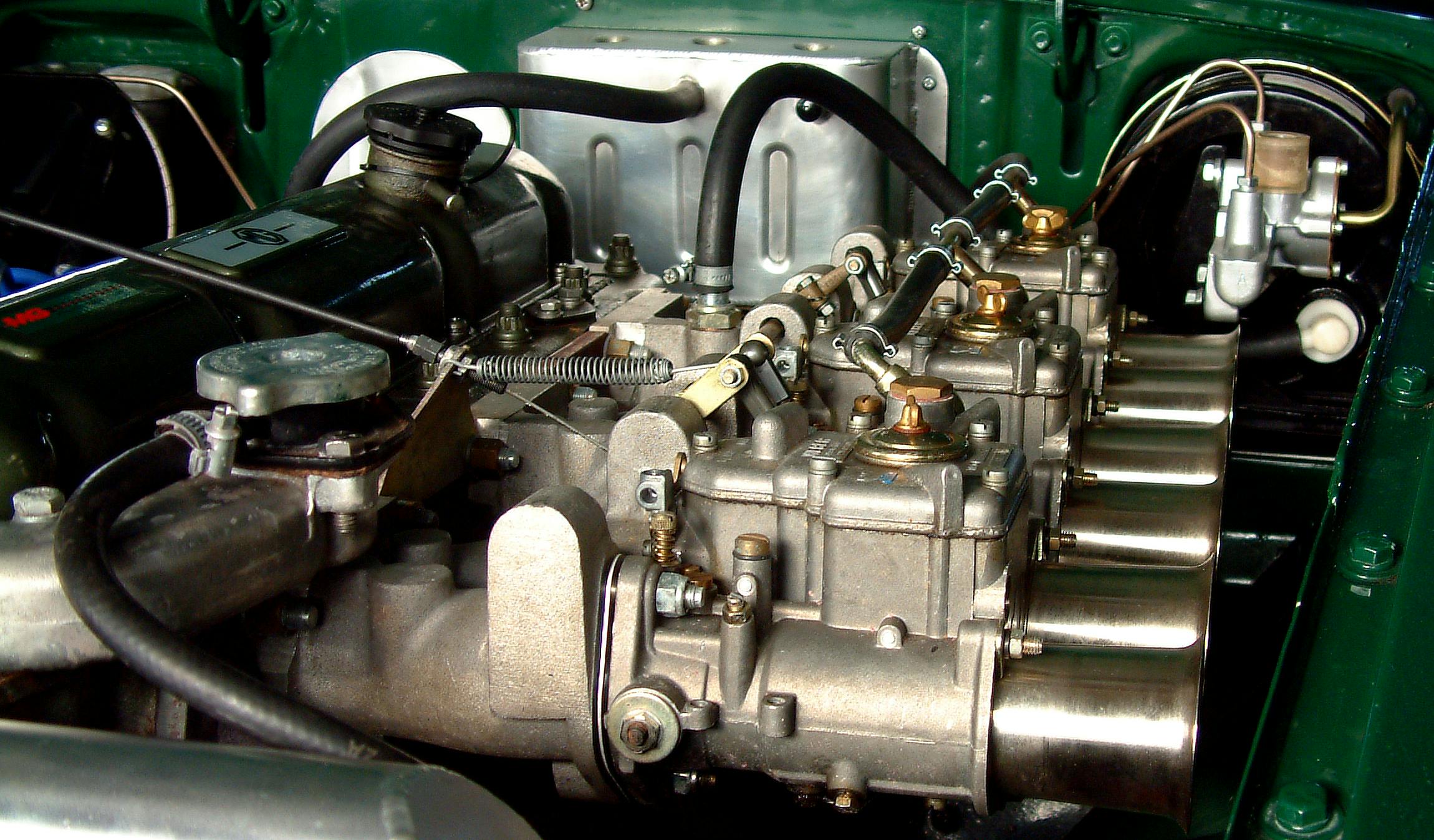

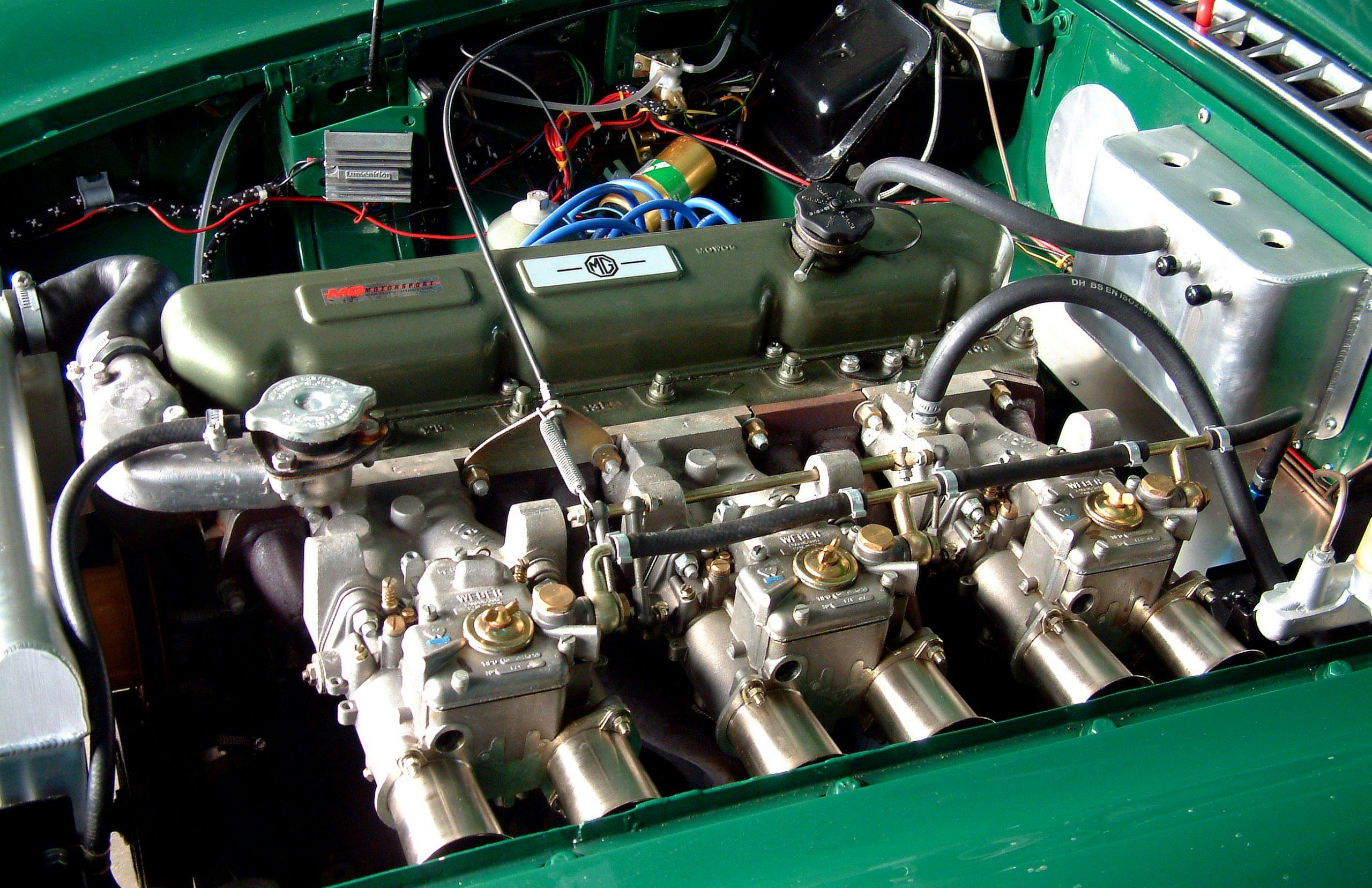

To turn a B into a C, the chaps at Abingdon swapped out the B-Series 1.8-liter four-cylinder and wedged in a C-Series 2912-cc straight-six from the Austin 3-Litre saloon, coupled to either an all-synchromesh four-speed or three-speed automatic. To make the longer engine fit, they replaced the MGB’s coil spring suspension with torsion bars. They also had to position the larger radiator further forward in the engine bay, which necessitated a massive bulge in the hood, trimmed by a chrome strip across the front. Aside from badges and 15-inch wheels (up from 14 in the B), that bulge is the only thing distinguishing the MGC from its four-cylinder cousin.

The six in the MGC was good for 145 horsepower, 50 percent more than the MGB’s 95 horses, and 170 lb-ft of torque. Top speed jumped to 120, and a 3.70 final drive made for relaxed highway trips, especially with the optional overdrive. But that extra grunt didn’t come for free, and the engine was far from perfect, at least in a performance car. While rugged and quite smooth thanks to its seven-bearing crankshaft, the C-Series was lazy and “reluctant to rev,” as Autocar put it in a period review. It was also heavy, with the MGC coming in at about 400 pounds more than the B.

More mediocre reviews followed the C’s big debut at the Earls Court Motor Show in October 1967, with Autocar also noting that “somewhere in the large BMC complex it has lost the ‘Abingdon touch.’” The C developed a reputation for understeer (in part thanks to early press cars having low tire pressure) and critics called out its high price. At $3350 in 1968 it wasn’t exactly expensive (an E-Type Jaguar cost over five grand), but it was pricier than other cars in its class despite looking almost exactly like the everyman MGB. You often only get one first impression in the car business. With the Big Healey leaving big shoes to fill, the MGC—compromises and all—had a hard time right from the beginning.

Not all the press was bad. Prince Charles may be an eco-warrior now, but back in his college days his first car was a blue MGC GT. And despite the C’s softer nature compared to the livelier MGB, a special lightweight MGC coupe also finished tenth at Sebring in 1968. Another finished sixth at the 84-hour Marthon de la Route at the Nürburgring.

Even so, a royal endorsement and some decent race results were never going to save the MGC. Most reviews were lackluster and the price was too high, so not enough people were buying one. MG also now came under the corporate yoke of British Leyland (BL), after the merger of British Motor Holdings (the successor to BMC) and Leyland Motors. After the merger, Triumph was no longer an external rival but a stablemate, and Triumph had two straight-six two-seaters of its own. The TR6 roadster and GT6 coupe were sportier and considerably cheaper than the MGC. BL generally favored Triumph over MG, anyway, so rather than develop the C and turn it into the car it should’ve been, BL gave it the axe. It quietly disappeared after 1969. The cheap and cheerful MGB, meanwhile, soldiered on for another decade. According to Hagerty insurance data, it’s the most popular classic British car in the country.

The final tally was about 9000 MGCs sold worldwide, with U.S. sales split between about 2500 roadsters and 1800 GTs (coupes). A major flop when you consider that MG sold over half a million MGBs and nearly 225,000 Midgets. And, being a flop is something that will always stick with MGCs, but over half a century later they have their fans and they are indeed collectible. They’re not highly coveted dream cars, but not cheap, either. Prices vary depending on condition, as they do for many British cars, and the gap between flawed cars and great ones is wide.

Like MGBs, Cs haven’t moved much in value recently. Although they’ve gained about 35 percent over the past decade, they’re down 3-4 percent from this time in 2015. For roadsters, MGC values range from $7300 for a rough car in #4 (Fair) condition to $49,500 for a car in #1 (Concours) condition. Condition #3 (Good) drivers can be had in the mid-teens, while solid restorations in #2 (Excellent) condition carry a value of $32,600. This is a little less than twice the value of the equivalent 1968-69 MGB Mk II, but also between half and a third the value of a 1967 Austin-Healey 3000.

Coupes, naturally, are a little cheaper. MGC GTs range from $6100 in #4 condition to $34,400 in #1 condition, with most cars (#3 and #2 condition) falling in the low teens to low-20s range. For all MGCs, the optional overdrive for the four-speed is a big plus but the three-speed automatic, a more popular option than you might think, commands a significant discount. The most anyone has paid publicly for an MGC was €140,000 (about $181,000 at the time), but that was a one-of-six factory-built lightweight race car.

As for driving an MGC, the grumbles about understeer are largely overblown (especially on modern radial tires), and in most situations you’ll never be pushing hard enough to find out, anyway. It is decidedly less lively than an MGB, both in terms of handling and picking up revs, but it does have a better ride. The C’s extra power and torque also allow it to cruise at highway speeds or more all day long. That’s when a B will run out of breath and start beckoning for the backroads.

If you don’t want the tradeoffs of an MGC (namely, sportiness and fun traded for that extra power), but still want a faster MGB, there is another avenue: the Rover V-8. Technically, MG did build a V-8-powered MGB in the ‘70s. MG never sold it in America officially, but plopping a Rover V-8 into an MGB is a common, straightforward, and affordable upgrade. You could probably do the swap yourself for less than the value difference between a B and a C. Plus, because the Rover V-8 is compact and aluminum (it actually weighs less than the B’s four-cylinder), it doesn’t change the car’s balance or character.

Imperfect but interesting, the MGC perhaps never got the chance it deserved. So what if it never lived up to the Healey that came before it? Today, it’s a much rarer, much more affordable classic that still looks great, and is still ideal for both tours and longer, more relaxed drives.

Like this article? Check out Hagerty Insider, our e-magazine devoted to tracking trends in the collector car market.