A.C.F. Howell metal finishers is a shrine to shine

In the early ’80s Adam Howell was smoking around the U.K. in his company car carrying out building surveys. But estate agency and property weren’t for him, and he looked about for a career change. In 1986 he set up A.C.F. Howell, metal finishers. So what took him from structural dampness to chrome plating?

When he wasn’t hammering up the M1 in his repmobile, Howell was busy restoring a Jaguar E-Type. Most parts were available from specialists such as Martin Robey, but the one bit that Howell couldn’t find was a replacement chrome trim for his coupe’s guttering. This would have stymied your author and many others, but Howell rolled up his sleeves and made his own replacement from brass strip which he then had chrome-plated. Word got around the Jaguar club to which he belonged, and before long our man was making sets of trim for other owners.

Realizing that he was deriving more pleasure from making parts for classic Jags than he was from peering around lofts, he set up the company that we are visiting today. Howell is not sure about the history of his Victorian-era workshops in Walsall, on the outskirts of Birmingham, but word is that it was once the home of an automotive engineering company—possibly one that manufactured steering wheels.

Back when Howell started the company it only occupied a small part of the premises that it does today. Expansion happened quickly and by the early ’90s A.C.F Howell had some pretty serious customers.

“Land Rover, which was owned by Ford at the time,” explains Howell, “wanted to build a limited edition of the P38 Range Rover. The standard car had door handles that were painted black but SVO (Special Vehicle Operations) had a plan to build a limited run of 100 cars that had chrome-plated handles and also a chrome surround on the center console. That was a pretty straightforward job for us because the numbers were low. SVO was very pleased with our work and it also impressed those in the production section of Land Rover. They asked us if we could produce parts for them for regular-production models and not just limited editions.”

Within less than a decade Adam Howell found himself going from making a handful of E-Type moldings to employing a small number of people in a corner of a workshop to running a business that had 90 staff and was delivering thousands of parts per month to one of the most prestigious brands on the planet. Those days came and went, as they often do when you’re relatively small cog in a very big supply chain.

Today A.C. Howell Limited is back where it started, helping enthusiasts and professional restorers by returning tarnished and rusting parts back to their gloriously shiny original condition, and from 90 staff down to a more manageable and friendly 18. You get the impression that Adam Howell doesn’t miss the glory days of dealing with big business and the associated worries—or the hassles of running a large company.

I’ve never done a ground-up restoration, but I’ve spent a lifetime titivating and rejuventating old crocks. Running restorations is the correct technical phrase. I know from experience that one of the most satisfying and downright sexy parts of fettling old cars is a trip to a plating company to collect freshly rechromed parts. Having passed through the area in which new jobs are unpacked and assessed, we’re in the part of the works where repairs are carried out before parts go through the plating process. For example, a radiator grille for a Jaguar XK is being soldered because a couple of the gills have broken.

Also waiting for attention is a huge front bumper. As he proves later on our visit, Adam can spot and identify an E-Type part from a hundred paces, but without looking at the job card he’s unable to identify this large bumper. Being an American car nerd, I am fairly sure it’s from a 1960s Pontiac Grand Prix or Bonneville. I used to own a 1972 Chevrolet El Camino pick-up truck and I remember clearly the excitement when its front bumper came back from the platers. I could have bought a new (pattern) bumper from America for not much more than the cost of the plating but the quality of the chrome would not have been as sensible.

“That’s often the case,” says Howell. “Preparation is absolutely key to a brilliant finish. Just the same with painting a car: If you have a poorly prepared base layer then the finished result will be poor. Some of the finishes that you see on pattern bumpers or chrome parts will only last a few years in our climate.”

Also in this part of the workshop is a machine that produces channeling like those parts Howell made 36 years ago for his own E-Type. There’s a drum of flat-brass strip that is fed into a succession of rollers that shape it into a perfect U-shaped channel.

“We made this machine ourselves,” says Howell, “and it does a fantastic job.”

But enough of this. I want to see where the magic happens. Where the chemistry and potions mix to turn a dull piece of metal into a shiny concours winning part of a work of art. The room where the actual plating is done. Howell leads us into a room in which there is a long row of vats—more than are needed today, but they were installed when the company was flat-out with its Ranger Rover work. Still, there’s plenty going on.

Chemistry is one of the many O levels that I failed to pass, but I do have vague memories of copper plating a spoon by dipping it into a solution of copper sulphate and then passing a current through the solution. “You’re in the right area,” says a generous and tactful Howell. Before we delve into the periodic tables, Howell has company chemist Dale Lyons try to explain the science to me—a brief overview of what’s happening.

“With the new guttering you saw us making earlier,” explains Howell, “we can take it straight to be nickel-plated and then after that chrome-plated. For parts like the bumper you saw, we first have to copper-plate it, then add a layer of nickel and then the chrome.” Howell shows us some parts that have been copper-plated and then polished. They look absolutely gorgeous in this finish and it’s almost a shame to carry on with the process. It certainly backs up Howell’s point about preparation being everything. Now to Dale Lyons—who, by the way, is a very hands-on person and doesn’t look anything like the typical stereotype of a chemist in a white coat with pencils poking from the top pocket.

“The process of electroplating is not particularly complicated,” explains Lyons. “The part or parts that you’re plating are placed in a bath of a salt of the coating material. The parts are then connected to the negative terminal of a source of electricity. Another conductor, composed of the coating metal, is connected to the positive terminal of the source. When the current is passed through the solution, atoms of the plating metal deposit onto the negative electrode or cathode.”

Lyons goes to explain that the thickness of the plating depends on the length of time that the current is passed and also the strength of that current. Up the current, and you plate more quickly. It’s all to do with Faraday’s Law. “Chrome is only in the bath for a few minutes,” explains Howell. “You’re aiming for a coating of chrome only 0.3 to 0.5 of a micron thick. If you apply too thick a coating of chrome it will crack and, equally serious, you may find that parts no longer fit together.”

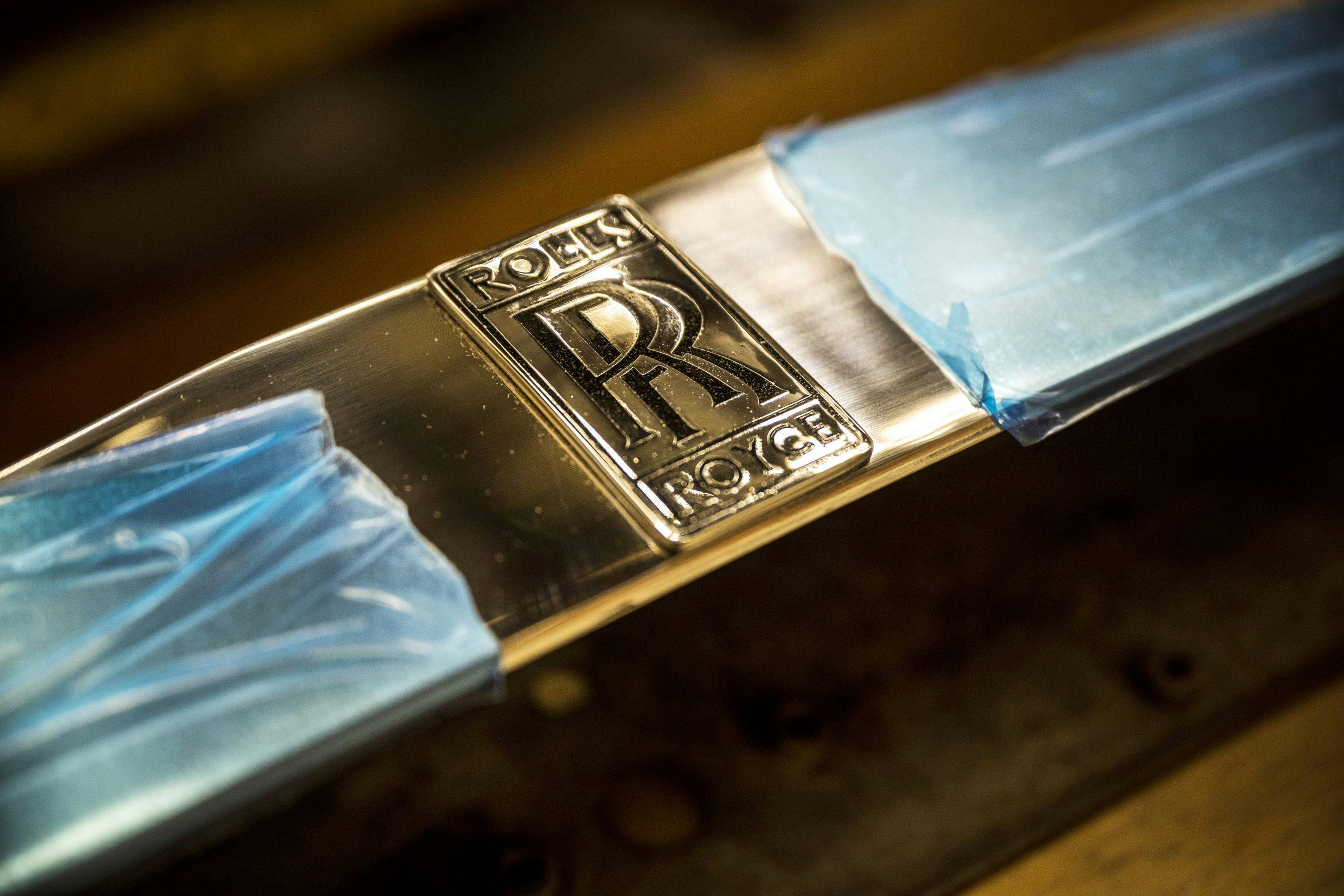

Once plated the parts are taken for polishing and then to final inspection. The variety of jobs on the go is amazing. Everything from a Rolls-Royce Camargue radiator grille to an exhaust from a classic two-stroke Suzuki motorcycle. And, fittingly, plenty of E-Type parts, including bumper sections. It seems a shame to put them back on the car. The company also has a large stock of Jaguar bumpers that can be used if a customer’s own part is too far gone. Incidentally, to rechrome a MK2 Jag bumper costs about £400 ($520, roughly). That said, prices are likely to have to go up in the near future. “We use lots of electricity,” says Howell. “Our electricity bill would make your hair fall out and the cost of energy, as everyone knows, is shooting up.”

Adam Howell parted with his E-Types (he had a small collection of them) a while back but is still a totally committed enthusiast. He has a Lamborghini Espada and a Ferrari 512 Boxer bought for a ridiculously small sum when prices were low. But the car I’d love to see is the Mercedes-Benz 450 SEL 6.9 that he restored himself. That generation of S-Class Mercs had the most fantastic big chrome bumpers. I’ll wager looking directly at those on Howell’s on a sunny day could damage your eyesight.

Via Hagerty UK