Preparing for the next Big Road Trip

I’m about to drive my 1972 BMW 2002tii—“Louie,” with its recently rebuilt head—on a 3,000+ mile road trip to and from the MidAmerica 02Fest event from Massachusetts to in Eureka Springs, Arkansas. That’s two 750-mile days each way, which essentially means pounding pavement during every waking sunlight hour (driving after dark, particularly after 14 hours on the road, doesn’t really work for me anymore).

While there’s a lot of alure in setting off for points unknown in a barely running rickety ratbox that you fix in real time as it breaks (I wrote Ran When Parked about such an adventure), the older most of us get, the less tolerant we are about such “adventures” that, well, suck. Breakdowns fall into that category, at least for me, particularly if they’re preventable. And so many of them are. On the one hand, the perfect road trip for a writer is one where one thing goes wrong that can be fixed safely and easily. Otherwise, no drama, no content. On the other hand, just because I write these columns doesn’t mean that I want to be thrown into a situation where I have to fix something by the side of the road, particularly if a breakdown may cause me to miss the event that I’m headed to. But on the other other hand, as a guy who can fix things, it drives me crazy if I’m just one part or one tool away from being able to extricate myself from a situation that otherwise results in a tow truck and an expensive repair bill.

So where do you draw the line on preparation and packing?

These days, my basic road-trip preparation philosophy is this: Fix the problems you know about, check the most common things likely to cause any vintage car to die, address any weak points specific to your make and model, carry the spares where you’d feel like an idiot if you didn’t have them (e.g., spare distributor cap, yes, spare differential, no), and bring a reasonable set of tools. Do that, and you’ll be in pretty good shape. At least if something goes south, you won’t do the wouda-shoulda-coulda thing.

So, let’s talk about preventive maintenance, spare parts, and tools.

Preventive Maintenance

Preventive maintenance before a road trip falls into two categories—dealing with the known and forestalling the predictable. Regarding the known, it’s pretty foolish to set off on a long trip with a car that has a serious known problem (for example, overheating or stumbling) and simply hope for the best. Cars are not biological systems. They don’t heal themselves. It’s way better to fix these problems before you head off into the great American pre-dawn than to simply hope that you’ve intimidated them into submission by your verve and charisma.

Regarding the predicable, I’ve nearly made a career about writing about what I call “The Big Seven” things likely to strand a vintage car (fuel delivery issues, ignition issues, cooling system issues, charging system issues, belts, clutch hydraulics, and ball joints). Other things can certainly fail, but they tend to either do so slowly, (e.g., brake pads gradually wearing out is far more common than brake failure), or to not be fatal to a road trip (e.g., if a rusty muffler blows a hole or falls off, the exhaust can be wired up).

Checking the fuel delivery system means inspecting the rubber fuel lines and replacing any that are cracked, pillow soft, or rock hard. There should be zero tolerance for fuel leaks. Old mechanical fuel pumps can fail slowly over time, pumping less and less fuel, until the car feels like it’s running out of gas because it actually is. In contrast, electric fuel pumps usually fail in a binary fashion; they either work or they don’t. Sometimes after sitting, they stick, in which case smacking them can sometimes briefly bring them back to life. I used to prophylactically replace old fuel pumps prior to road-tripping, but owing to the questionable quality of replacement parts these days, that’s now a judgment call on which I fall on the side of leaving them in and bringing spares.

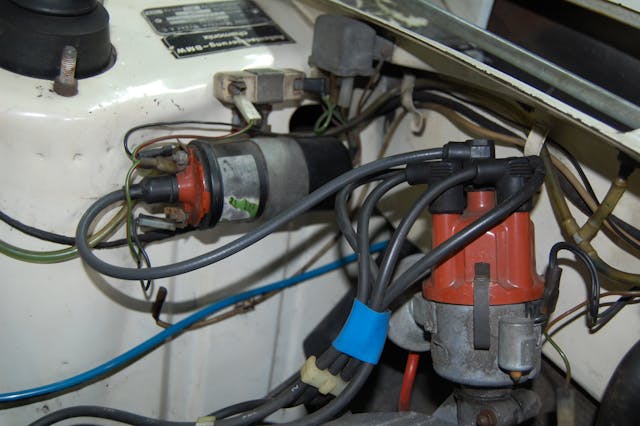

Ignition issues are common in vintage cars, as mechanical contact points invariably close up over time. Especially on cars that are road-tripped, I’m a big believer in replacing points with electronic breaker-less ignition such as Pertronix, but if you rely on points, be certain to inspect them for pitting and to check point gap / ignition well before a long trip. Inspect the spark plugs and replace them if they’re carboned up, and check the inside of the distributor cap for corrosion and cracks and the plug wires for abrasions that can cause them to arc to ground.

Cooling system issues come primarily from leakage or overheating. As with the fuel hoses, check the coolant hoses and replace any that are pillow soft, rock hard, or cracked. If it’s been decades since the hoses have been off the car, removing them and scraping the corrosion off the metal coolant necks is a good way to forestall leakage. Inspect the underside of the water pump to check for a coolant trail. Grab a fan blade and rock it fore-and-aft to check for bearing play. A tiny amount of play is acceptable, but obvious looseness indicates impending bearing / seal failure. If possible, drive the car in temperatures similar to what you expect on the road trip. If it runs hot, the odds are that the radiator isn’t up to the task. Upgrading to a higher-capacity radiator before a trip is money well spent.

Charging system issues involve the alternator, voltage regulator (which may be internal to the alternator or external), and the wires connecting them to the battery and to ground. When the engine is running, the voltage at the battery should read between 13.5 and 14.2 volts. On vintage cars, it may be a little lower, but if you read battery voltage of 12.6 volts while the engine is running, the alternator is not charging the battery, and the battery will run down and eventually will not have enough juice to fire the coil. I never road-trip without a cigarette-lighter plug-in voltmeter or a plug-in junction box with a voltage readout as well as multiple USB ports. You really want to know that the alternator has quit before the car dies.

Belts overlap with the cooling and charging systems, as vintage cars often have a single fan belt that runs both. In addition to breaking, belts can lose the ability to be tensioned. I’ve seen cars overheat and batteries run down because the rubber bushings in the alternator are worn out, causing it to cock forward and making it impossible to keep the belt tight.

When clutch hydraulics (the clutch master and slave cylinders) fail, the clutch pedal will go to the floor without causing the clutch plate to separate from the disc, making it impossible to put the car in gear and difficult to shift. Impending failure is sometimes accompanied by visual fluid loss. A leaky slave cylinder is usually obvious, but depending on the design of the master, the leak can go into the pedal bucket and be difficult to spot. As both the clutch master and slave are a pain to replace on the road, if the car is 40–50 years old and running on its original clutch hydraulics, prophylactic replacement is best.

If a ball joint fails, the wheel folds under the front fender and you lose control of the car. While the same loss of control can be said of failure of other steering components like tie rods, the ball joints are the steering components that take the pounding from the suspension, and thus are more likely to fail catastrophically than tie rods. Jacking the car up, setting it on stands, and squeezing the ball joints with a big pair of slip-joint pliers is essential to ensure a safe trip.

(Note: It should go without saying that thing #0 is tires. While I’ve been known to take liberties with old tires for short drives to cars and coffee events, it’s foolish and unsafe to set off on a major road trip with dry-rotted rubber.)

In addition to “The Big Seven,” there are a few preventive maintenance issues that I address before a trip.

Brakes: Just because I don’t include brakes on the list of things likely to strand you doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t be in top condition before a long trip. After all, you never know when a semi is going to stand on its air brakes right in front of you.

Valve adjustment: Valve clearances usually change pretty slowly on a broken-in engine, but if they haven’t been adjusted, it’s smart to do it before hitting the road. The danger is valves that are too tight. If they don’t fully close, they can start to burn.

Fluids: In the weeks before a trip, pay attention to the car’s fluids by looking underneath it for leaks as well as checking oil, coolant, and brake fluid levels. If the trans/diff fluids have never been replaced or even checked during your ownership, now’s a good time to do it. If you run conventional oil, you can easily reach its recommended change interval during a long road trip, so starting with a fresh filter and clean oil is a good idea

Under-car stuff: If a car has flex discs in the drivetrain (called “giubos” in European cars, “Rotoflex couplings” in Brits), jack up the car, crawl under it, and check them for cracks. The same is true if the driveshaft has a center support bearing. When the rubber begins to split, you’ll often hear a thumping or a whacking sound. You may be able to get hundreds of miles out of them before they let go completely, but when they do, they can bend or break the metal flanges that they’re attached to, so it’s best not to reach that point.

While you’re under the car, check the exhaust hangers and the bolts holding the transmission support bracket and the shift linkage. While these are unlikely to derail a trip, it’s better to address them in the garage than by the side of the road.

Wheel bearings: Jack up the front of the car, grab each of the front wheels at 6 and 12 o’clock, and then at 3 and 9 o’clock, and rock them to check for play. Play at 6 and 12 o’clock is coming from the wheel bearings. A small amount of play is fine, but a lot means loose or bad wheel bearings, and should be addressed before a trip. Play at 3 and 9 o’clock is steering play, which could be coming from tie rods, steering box/steering rack, or other components. Like with the wheel bearings, a little play isn’t the end of the world, but if there’s massive amounts of wiggle, it should be fixed. Do the same 3-and-9 test on the rear wheels. Rear wheel bearings live pretty long on most cars. When they begin to fail, there’s usually a fair amount of warning with a loud howl and/or rumble, but replacing them usually requires bearing / hub pullers. Better to catch them early and do them in the garage.

Spare Parts

When I used to road-trip solo, I’d bring enough spare parts to repair just about any of the issues named above. I once even packed a spare radiator, as I was uncertain if the one installed was up to the task. I laugh at that now—I mean, if you don’t think the radiator in the car is beefy enough, and you’ve already bought another one, why not install it prior to the trip?

But a couple of dynamics have somewhat lessened my pack-rat habits. As I said above, the poor quality of replacement parts these days makes me more likely to leave working parts like the water pump and fuel pump installed, and pack spares. Also, traveling as part of a caravan has made me feel the need to carry less. For example, if I’m carrying a spare water pump, I used to think that that meant I needed to carry everything needed to change it by the side of the road or in a parking lot, which included two gallons of pre-mixed antifreeze and a catch basin. Now, I take advantage of the fact that, if something happens, another road-trip member can run to the nearest Autozone and buy these things.

Still, I don’t feel prepared unless I also have a length of fuel hose, upper and lower radiator hoses, a fan belt, and a spare set of ignition parts (plugs, points, condenser, cap, rotor, and coil). I’ve never had a properly installed Pertronix or other electronic triggering module die on me, but having a set of points and a condenser as a back-up wards off bad juju. Some think that’s an admission that electronic ignition modules are likely to fail. It’s not. I mean, let’s face it, if you’re running points and condenser, you carry a spare set of points and a condenser anyway.

Should you bring a spare alternator and regulator? I often do. At a vintage BMW event, someone usually needs one, even if it’s not me.

Lastly, there’s the issue of known failure points on your particular car. For example, a BMW 2002tii is a mechanically fuel-injected car. Although the injection system is remarkably robust, the lines connecting the injection pump to the injectors are plastic, and if they crack or rub themselves to the point of perforation, no store will have them in stock. Similarly, the little o-rings at the top of the injection pump can leak. So I pack spares for these.

And obviously, make sure you have a decent spare tire.

Tools

Back in the day, I used to carry enough tools to repair a small plane. In my garage, I have two big multi-drawer toolchests, and a smaller low one on rollers that also doubles as a stool. Over the years, I’ve figured out which tools are the most commonly used ones, and I’ve put them in the roller chest, so prior to a road trip, I used to repack what was in the roller chest into portable plastic containers and load them in the trunk. The past few years, though, I’ve stepped back from that, and instead I’ve put together a small, dedicated tool chest that I throw into the trunk of any vintage car I’m driving farther than around the block. I now take that same small tool kit on road trips and add to it as necessary.

I used to make sure I had a good set of both internal and external snap-ring pliers with me. After all, you can’t replace a clutch slave cylinder on a BMW 2002 without them. Of course, if you need the snap-ring pliers, you’d also need the clutch slave cylinder, and over the years I’ve put that in the preventive maintenance category rather than the spare parts category, so the snap-ring pliers usually stay at home. Besides, if something breaks on the road and I need another tool, a convoy partner can always make a tool run. I will, however, bring my good set of flexible nut drivers in case I need to loosen a hose clamp. And I still run with a lightweight aluminum floor jack and a pair of aluminum jack stands.

Sundries

Beyond the mechanical tools, I also carry a timing light, fuel pressure gauge, remote start switch, multimeter, wire stripping/crimping tool, a variety of crimp-on connectors, and a pair of alligator clips attached to long wires so I can test things by wiring them directly to the battery. I’ll also throw in a Tyvek suit and a few pairs of gloves so that if need be, I can skooch under the car without getting filthy. And paper towels. And a can of Fix-O-Flat, a can of starting fluid (still an astonishingly effective method of distinguishing no-spark from no-fuel in “car dies” or “car won’t start” problems), and a fire extinguisher. And a coat hanger—the only item that’s a part and a tool. And J-B Weld, because there was that time I used it to fix a cracked cylinder head. (In truth, that J-B Weld episode fell firmly under the “You’re an idiot if you set off on a road trip with a known problem” banner but hey, it made for a great story.)

That’s pretty much it. Fix enough in advance and bring enough with you that you won’t feel foolish if something breaks. There was that time my little Winnebago Rialta RV popped a brake line and I had to leave it overnight at a shop and pay them to fix it, but even though I have a spool of copper-nickel brake line and a flaring tool, that’s just not something I’m going to bring on a road trip. I mean, there’s prepared and then there’s paranoid.

***

Rob Siegel’s latest book, The Best of the Hack MechanicTM: 35 years of hacks, kluges, and assorted automotive mayhem, is available on Amazon. His other seven books are available here, or you can order personally inscribed copies through his website, www.robsiegel.com.