Smithology: Who ever saw a refrigerator as pack animal?

The internal-combustion engine is remarkable. An alloy box converts a small dose of fuel into a relatively large quantity of work, and for a relatively long time, with relatively little maintenance. The last century has seen that work run the gamut—from diesel locomotives to 200-mph family sedans and the starting of a pair of afterburning turbojets that once allowed one of our greatest mechanical achievements to fly coast-to-coast in just 64 minutes.

Human existence runs on this stuff, and yet this stuff could not run without access to a humble, carbon-dense liquid. A recirculating pool of lubricant designed to transfer great force between objects while simultaneously guard-railing against a hundred possible catastrophes of friction and pressure. The downsides are simple: First, no lubricant is perfect; on a long enough timeline, any machine wears out. Second, every engine consumes fuel and oil in fire, and nothing burns without transformation. Stray bits of form-altered carbon eventually reach suboptimal places—the troposphere, the back of an intake valve, even just that spot on your tailpipe that smudges a pant leg when you lift groceries into the trunk.

Your fortunate narrator has access to many tailpipes. (Not a euphemism! But thank you for asking.) One pair of those pipes belongs to the 2019 Volkswagen GTI that my wife bought a while back, her first new car. In addition to hauling four grown adults in comfort, the VW spits 37 observable miles per gallon at 70 mph and makes corner entry happen with some jazz on the taillights. Nearly two years and 20,000 miles in, ours has been virtually hassle-free.

Except for one thing.

A thing not unrelated to oil or carbon.

Which is why I was recently on Southern Michigan freeway doing 4800 rpm in third gear for 20 minutes while a small German automobile literally yelled bits of its head off.

More on that in a moment.

***

A short tangent for a series of lightly relevant points:

- In January of last year, my little family moved from the West Coast to East Tennessee. I grew up in the American South; my wife did not. So that she might feel at home in this great new land, I spent hours pondering ways to increase her comfort.

- Then I went online and selected for purchase a tasteful, reassuring, NASCAR-licensed Dale Earnhardt, Sr. commemorative #3 front license plate. I installed this plate on the GTI shortly after we arrived in Tennessee, but I did not share that fact with the most important person in my life, lest my excitement make her think it was a joke.

- It was not entirely not a joke.

- But only because she had no idea who Dale was. Or why a sportsman’s lip rug can double as cultural force, or how a modern and worldly individual can love road racing from childhood but also unironically find golden-age NASCAR heroes deep glorious.

- My wife is a detail-oriented professional copy editor; I am an easily distracted writer who often mispronounces the word “sandwich.” That said, she occasionally trails me in vehicular specifics. She didn’t notice the Dale plate for almost three months.

- On the day in question, we met in the kitchen, where my head was buried in the pantry, chasing afternoon cookies.

“Where did that license plate come from?”

“We do it for Dale,” I said, deep in the Oreos. “Have for years.”

A sigh. “Who is that?”

I turned from the cabinet, cheeks full of samwich cookie, like a chipmunk. Face in mock horror. She eye-rolled.

“I’ll take it off … later?”

She began cleaning a stack of dishes, didn’t look up. “Mmhmm.”

“I will definitely take it off later.”

- I did not take it off later.

- That said, she eventually said the plate made the VW look friendly. Which it did. Inasmuch as a scowly little German doorstop can look friendly.

- Over the last 18 months, as the world generally lacked good cheer, I found said friendliness encouraging. A consolatory light in the driveway.

- Especially when the thing started running like trash.

- Early this year, the GTI began idling funny when cold and surging intermittently on boost. There was no check-engine light, and the dealer couldn’t replicate the problem. At least it believes in the Intimidator, I thought.

- Over the last 2000 miles, the surging grew so annoying that I began to drive around purely on part throttle, where the car mostly behaved. My wife, small-throttle by nature, never noticed the issue.

- I also kept postponing another dealer visit.

- This ostrichy problem-avoidance was precisely as ridiculous as it sounds, but when you travel a lot for work and find car dealers akin to a dental visit where someone tries to upsell you larynx undercoating, procrastination is like water. Necessary for life.

- That plate looked so good, though! Sparked joy.

***

So much to pull apart there.

The car seemed friendly. You probably know what that means. We get attached to stuff that takes us places, literally or figuratively. Fulcrums that balance potent bits of the human experience. Spend enough time around certain machines, you can come to view a logical stack of steel as chipper or vindictive, playful or mercurial, illogical and full of ghosts. People say the same of ships and castles but not dishwashers or power plants. It’s probably tied to the light unease we occasionally feel when trusting pulse or livelihood to inanimate object, and the fact that nobody dies if a Maytag craps its soap tray.

B.B. King famously called his guitars Lucille, told people they didn’t always cooperate. Charles Lindbergh traded the dead-eyed “Ryan NYP” for Spirit of St. Louis, then found himself talking to an engine over the Atlantic, urging it to keep going. On the other side of the divide, we give refrigerators dull names like Kold-O-Mat 5000, expect perfection every day, grow grumpy if they try to start a conversation.

The GTI’s running problems struck a chord. Almost like broken trust. Neither my wife nor I had previously owned a new car. Before signing the check, I had never even read a vehicle warranty. After years of watching my family leave our driveway in 100,000-mile vehicles, there was something awfully compelling about a perfect new object that I didn’t have to work on or pay to fix.

Until, of course, it stopped being perfect.

The more I chewed on it, the more the timing offended: Twenty thousand miles on the clock! A dealer that couldn’t find squat! As if someone—some thing—had made a choice to be obnoxious, instead of simply working properly or not.

If this all sounds patently insane, that’s probably because it is. And yet.

Everything breaks, but expectations count. Consider how certain behavior can seem totally acceptable in one situation and over the line in another. Years ago, on a brisk summer morning at another job, a new Ferrari I was testing failed to start. Faced with a dash full of glowing lights, I simply shrugged, climbed out, and locked the car. Then I went back into the office and had a second cup of coffee. Ten minutes later, I walked outside and tried again; the car lit off immediately. Nothing about this seemed out of place; it is what we have been taught to expect from devices or people of high emotional amplitude.

That strange gap between what we knowingly accept, and what we think we shouldn’t have to. Always sensible in the moment, but on a certain level, arbitrary as dice.

Still. Curiosity never hurts. I started reading the Internet a bit, began to wonder if the GTI had a bum sensor or a boost leak. The symptoms roughly aligned with fluctuating intake pressure. Late one night, in a hotel during solo work travel, I happened to be texting about the problem with an industry-consultant friend. Car people being what they are, this friend then texted another friend, an anonymous credentialed type who knew … Volkswagen things.

Answers returned moments later. VW once published a technical paper on carbon buildup in the company’s direct-injected engines. Our friend-of-a-friend suggested the GTI’s issues came from such deposits, or yes, maybe a boost leak. It is apparently not uncommon for VW techs to run certain motors on the freeway at 4500 rpm or higher, and for at least 20 minutes, in order to break down accumulated garbage and aid drivability; the key is sustained, soaking heat. Call it the modern version of the Italian tune-up.

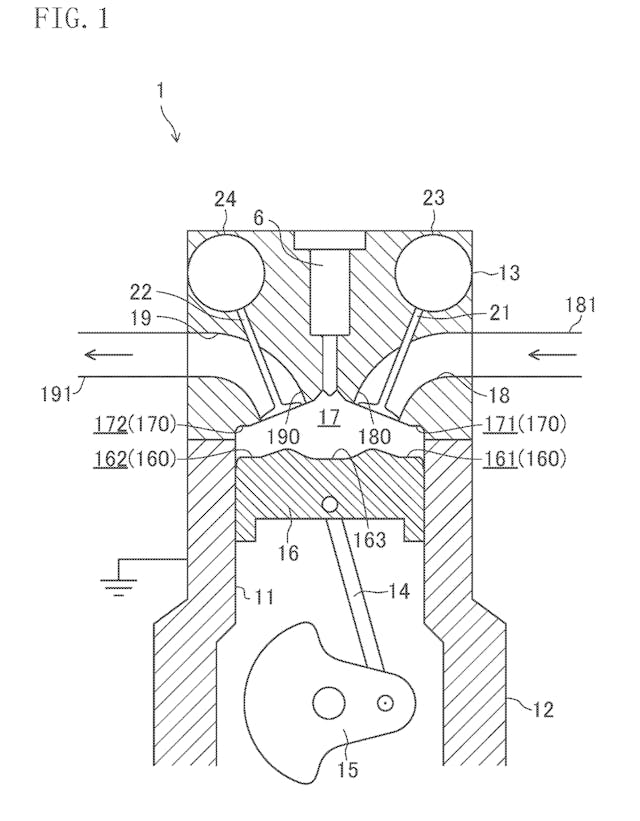

Carbon build-up and direct fuel injection have long traveled hand-in-hand. The issue is often compounded by city driving, or any long-term use favoring relatively low rpm and short-term cycling. On top of this, many manufacturers now use variable valve timing and valve overlap to coerce spent exhaust gas back into the intake manifold. This practice aids emissions—it’s effectively a form of EGR—but it also nudges certain carbon compounds back in the direction of hot oil, where they react and grow sticky. Finally, as a sort of coup de grace, because a D.I. engine keeps its injector nozzles in the cylinders—that’s the “direct” part—the detergents in modern fuels are less practically effective on intake ports and valve backs. (Gross and lightly inaccurate simplification: You can’t clean what you don’t touch.)

By no small coincidence, when I sent that text, I was in Detroit for a track test of the 2022 GTI. As benchmark, I borrowed my wife’s car for the drive from Tennessee. On the eight-hour trip home the next day, trudging down I-75, I figured, hey, 4500 rpm, maybe a bit more noise for 20 minutes, can’t hurt?

More light insanity: In the age of hypertall drive ratios and ten-speed automatics, in a country with speed-restricted highways, you rarely hear an engine loud at cruise. If you are a certain kind of person, you could maybe watch the oil temp creep up during all this and get to thinking the little guy shouldn’t work so hard. Even if you yourself have driven on autobahns in countless modern cars at high rpm for far longer than that. Even if you know there’s nothing in harm’s way.

Who likes beating a mule?

Conversely: Who ever saw a refrigerator as pack animal and wanted to give it a break?

The crutch in thinking is forgivable. Nobody wants to know the world less than they already do, and parts of it can be too complex to understand at a glance. Known order is thus swapped for unknown disorder and human reaction. Which is how you can look at a large pile of steel in your driveway and feel as if there were some sort of bargained agreement for mutual care. Even if no object ever owes you anything, or even understands the conversation.

Forty-eight hundred rpm in third gear in a 2019 GTI is 75 mph. Any faster and engine noise grew annoying; any slower and traffic left us behind. The process was louder than a sixth-gear cruise but also not entirely unpleasant, because German fours are generally made to sound decent, or at least not grating, in that kind of use.

Twenty minutes passed. I waited another ten for good measure, then dropped back into sixth. The engine returned to inaudible.

More to the point, the car ran significantly better, surging and lame idle gone.

Several hours later, I was further south, nearly home. At the Kentucky-Tennessee border, where accidents slowed the highway to a crawl, I detoured onto rainy two-lanes while listening to Justin Townes Earle’s “Harlem River Blues.” Ribbons of pavement and gravel wound around stone cabins and swollen creeks in dark valleys wrapped with fog. A thunderstorm crept over the horizon. The VW became a warm little pup tent, quiet and dry, skating over the land. We rolled into the driveway shortly after dark.

Another trip down, another thousand miles on the odometer. And a problem fixed, for now. I’d tell you that the car liked it, but that’s gibberish. Cars don’t have feelings; cars can’t be happy or sad; heartless machines cannot suddenly return a little more jazz and spark than they ever have, find a new peak following light attention for malady.

Except, of course, in those rare moments, impossible to rationalize or explain, when, wonder of wonders, they do just that.