Smithology: A tenth and a half, in a back pocket

On Sunday, May 30th, 2021, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway hosted the 105th running of its signature event, the Indy 500. One of the few motorsport landmarks still capable of capturing the public fancy, the race is a fest of pomp and spectacle—nearly two million dollars to win, the world’s largest single-day sporting event, at the largest sports facility on earth, a feeling on the ground that can swell and sing as nowhere else. Men and women slide hunks of carbon fiber around a 230-mph bullring just as fast as they can, fighting crosswind and exhaustion, risking their lives for hours on end.

The pull of the place is such that more than a few individuals will return next year and try to qualify despite not being full-time IndyCar shoes, or even full-time professional drivers. Colorado’s J.R. Hildebrand is one of those people. He is also an Indy 500 podium finisher and former rookie of the year. This May marked his eleventh in Indianapolis. His first, in 2011, ended in one of the most heartbreaking finishes in Speedway history; he led the field on the last lap only to crash in the final corner.

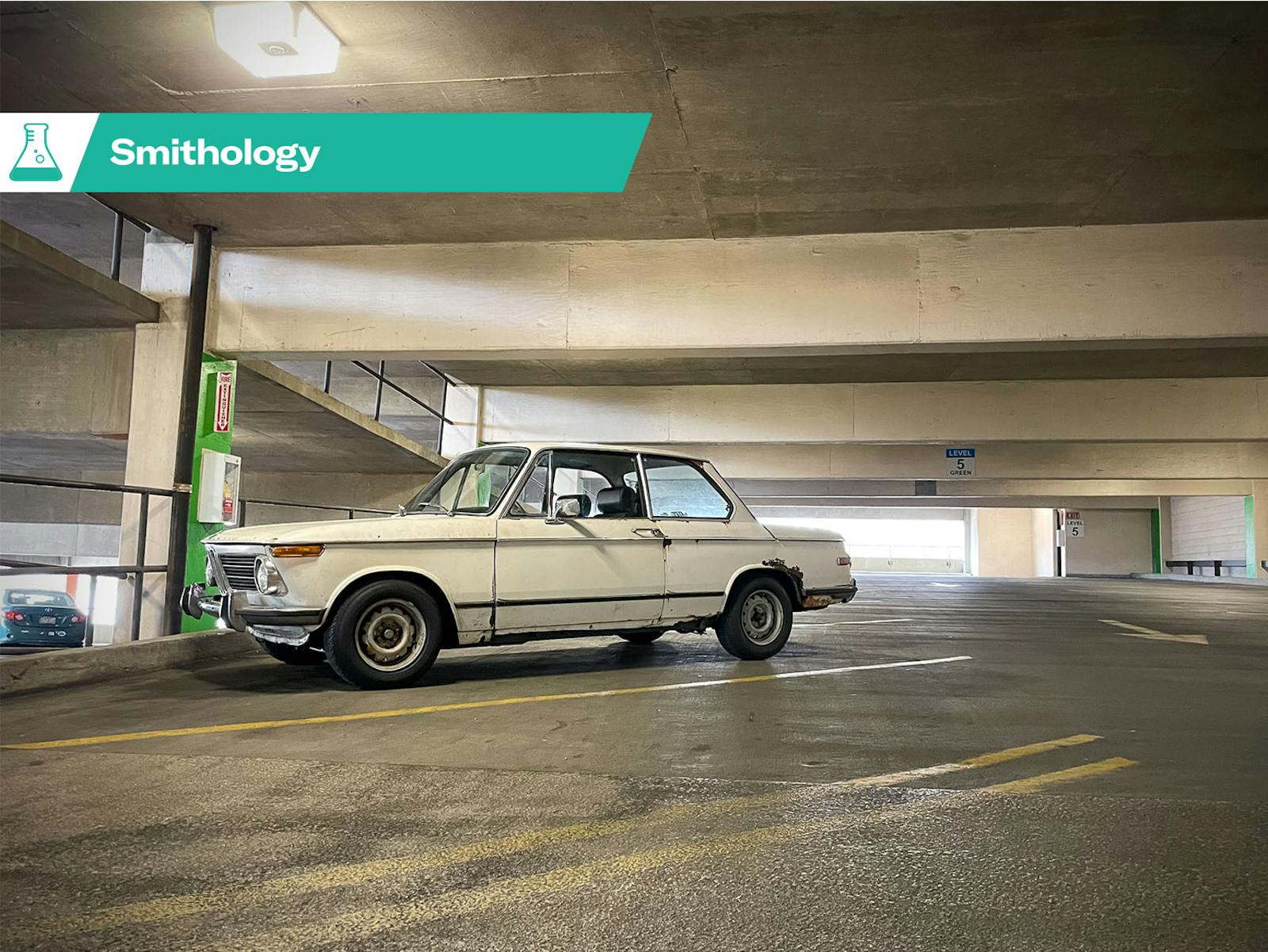

Hildebrand finished 15th this year, driving for racing legend A.J. Foyt. The pairing was apt; Hildebrand is a student of history who once commissioned a pair of custom Vans featuring the 1967 STP turbine car, and he plans to run a current Indy car up Pikes Peak in 2022, because that sort of thing used to happen all the time and should again. For 2021, he traveled the 1100 miles to the race in “Rosie,” his 1960 Cadillac Coupe Deville.

I called Hildebrand last week, the day after he got home, to discuss the pull of the country’s fastest coliseum and why a person might go back after countless ups and downs. What began as a casual chat morphed into an examination of athlete mentality, the nature of failure and self-analysis, and why anyone chases improvement with anything.

***

Sam Smith: You’re no longer in IndyCar full-time, but like a lot of people, you keep going back to the 500, even on long odds. Why?

J.R. Hildebrand: One, I can’t get it out of my head. I spend the entire year thinking about how to win the Indy 500, or even just being in it. About the little things that give you a chance. And two, it sounds weird, but it just feels like a thing to go do, as a human, that matters. Worth the obsession.

SS: Foyt has been going back for 63 years. Bobby Unser used to hop in his RV every spring, drive in from his place in New Mexico. More than a few drivers have said the place just starts to feel like part of you.

JRH: Part of it is that, as an IndyCar driver, it’s where the car does what it’s meant to do. It’s also just a unique combination—we’re all just… supposed to be here. There’s supposed to be 33 people in this race. I’ve been one of those people for the last 11 years. There’s nothing about this that ever feels out of place. I think about qualifying at the 500 as its own thing—a human experience that I can’t get doing anything else.

It’s not just that the race has some magnitude to it. Driving the car there is a completely different experience than it is anywhere else.

SS: From moment one, right? You go out one at a time in qualifying, that ancient temple all to yourself, everyone watching, the car in its most knife-edge trim, almost too unstable, one of the fastest closed-course laps in the world.

JRH: A lot of this swirls around a general idea—there are so many people where this is the one thing they’re most heavily invested in during the year. For every mechanic, for every engineer, wife, kid, father, mother—within that community, there’s an extraordinary amount of effort that goes into being at your absolute best in these handful of moments. Nobody puts that degree of effort into any other set of moments throughout the year.

As a group, a team, the situation demands your best because everybody else is putting in theirs. You don’t show up at, say, Detroit feeling that way. The rest of the season, there’s so much inconsistency in terms of the degree of effort everyone is putting in.

SS: Which is funny, right? Nobody shows up at Detroit or Laguna and says, “I’m saving the best me for Indy.” But commitment does vary, intentionally or not, because people are human.

JRH: Indy is just a different thing. You have to figure out how to extract your own maximum, just to live up to everybody else. And then qualifying, you’re by yourself. Sometimes you’ve got a shot at the front row. Sometimes you have to work to not be on the last row. The stakes are really high. Screw up badly enough, you might not make the race. Then you’ll be sitting on the sidelines for this thing you spent an entire year thinking about.

I know this about the Indy 500 a decade from now: If I’m going to qualify, I’ve got to be the absolute best version of myself that can possibly exist in that moment. The reward is so extraordinary, but the risk is just as great on the wrong side of it.

SS: I love how performers pull themselves out of the moment. A musician at Carnegie Hall, an Olympic gymnast, Turn 1 on national TV—your whole job is to not get spooked by the context. At the same time, one of the joys of Indy is bathing in meaning and tradition. How do you reconcile that?

JRH: I think every driver has a different response. The zone, athletes of all kinds describe that the same way. Everything just slows down. Your timing is just naturally perfect, you feel totally aligned, almost like you see everything coming a little before it happens.

SS: What psychologists call flow state, right? Everyone gets there so differently, which is remarkable, because the end is the same.

JRH: Frankly, I spent a lot of time just over the last few seasons—deep into my career—trying to understand that a little bit better. Because it’s one thing to say that everybody experiences it the same way, and it’s another to try to figure out how to tap into it more regularly, or with more complete intention.

SS: Some just see it as luck, and others try to stack the deck to get there.

JRH: I’ve been lucky, I’ve driven for a lot of good teams. At this point, I know what I’m looking for out of the car. It’s something entirely different to say, “That’s great, maybe it gives me a leg up. But there’s still this part of going out and executing that’s just on me.”

I heard Scott Dixon talk about it this year—he was really nervous before qualifying. Which I thought was really interesting.

SS: One of the greatest of his generation, a beast in a race car. Nervous.

JRH: You look at athletes in these situations like, “Oh, they just have to tune everything out.” For me, the thing that really allowed me to access what I’m looking for more quickly, with a deeper understanding of what I’m doing, was to just say, “Look, I’m going to qualify for the Indy 500 today. I’ve got these four laps to do it.”

After a point, I can’t control exactly what happens. I’ve done this enough now that I know how much better I feel when I know I’ve gotten the best out of myself. That will stick with me. It has nothing to do with how fast the car is, whether we chose the right gearing strategy, all this stuff that, once I go out there, I can’t change it.

That’s been a really powerful alignment tool. To basically say, “In this moment, I’m doing this with something in my heart, for everybody around me. Because if I do my best here, that’s good enough to pay back everyone’s effort and stress. But basically, I’m going to do this foremost for me, so I know I’ve gotten out of it as much as I can get.”

SS: Which can read as selfish, but really isn’t.

JRH: If I was just competing in the IndyCar series? If I didn’t have qualifying at the Indy 500 to force me to figure that out, because there’s so much at stake, it’s such an incredible experience to get right or wrong? I’m not sure I would have thought about it as deeply.

SS: If you didn’t know much about racing, you could get to thinking the car is the only potential source of problems.

JRH: To be frank, I only started thinking about it because when I last raced [IndyCar] full-time, in 2017, I didn’t enjoy it that much.

SS: Why?

JRH: We had a really up and down year. There were places that we were really good and tended to execute—I ended up on the podium. Then, a lot of places, as a team, we didn’t have our act together, we did lousy, and that’s just racing, how it goes.

Partway through the season, it became almost infuriating that there wasn’t the time or ability to figure some of these things out. I realized after the fact that it was impacting what I brought to the table. As a group, you’re so focused on how to get the most out of the car.

SS: Everything else can seem less important, even if it’s not.

JRH: I had become a little bit detached from what I was there to do, which was to just be a race-car driver. You don’t continue that just because it’s fun. When you’re getting your ass kicked, it’s hard for it to be fun.

I realized a couple of things. And one of them was that this should not be something, under any circumstance, that I almost despise doing.

SS: Was that one single moment of wake-up, or just a long trudge of learning?

JRH: There were a couple of times during the season, towards the end of the year—there was something, in the way the car was working, that I just was not comfortable with. But also places where I also simply needed to do something different. Be a little bit more in tune with would work as a driver—bend it in a little later or slower, brake a little differently, whatever—the whole process of the thing had become so mechanical to me at that point.

It was so much effort! [Laughs] Just to adjust something that, when everything’s going fine, you do without thinking.

SS: There’s an old line that goes something like, “Being good is easy. Failing well is hard.”

JRH: When you’re in a car that’s consistently good, you’re not thinking about [the car] part of it. This state where you’re just naturally reacting, you’re aware of your surroundings, a bit ahead of them, the wind and whatever else.

For me, being my best was now kind of attached to getting a certain feeling and reaction from the car. I didn’t realize at the time, but looking back—when I was still looking for what I felt like I needed, I wasn’t really in that naturally adaptive state as much.

SS: What kind of gap are we talking about?

JRH: Between an absolute out-of-my-mind performance and feeling totally disconnected? Maybe only a tenth [of a second] and a half or something. But in IndyCar? If I had a tenth and a half in my back pocket for my entire career? I’d probably be driving for Roger Penske, winning championships.

SS: That thing where your perception can influence your actions, including your perception.

JRH: I used to think, “I won’t focus on the result, but I’m being paid to drive here for this team.” To some degree, success for me was important to pay back the opportunity.

Once that went sideways, I felt this super-heavy weight of not achieving it, which created a spiral. You know that’s not the right head space. You can be totally aware of how you need to ignore it, do what you’re there to do.

SS: And yet.

JRH: The difference between attaching yourself to your own feeling good versus just trying not to feel s*** is massive, in terms of how motivating it can be.

I started trying to figure it out. I guess the outcome was just realizing that it really is being 100 percent committed to how good it’s going to feel to do your best, regardless of what’s going on.

SS: With the 500—drivers have talked about this, the race being so long that it produces a sine wave of emotion. When things start going right, with packed stands and all that momentum and humanity, what’s that like?

JRH: At Indy, when the car feels the way you like and you’re rolling, there’s part of you inside that just—when everything starts to click, you can hear it over the radio. You can see it happening on track in front of you. You feel it through the steering. When the car just does what I want it to in the first hundred feet, that all by itself sends a lightning strike through your body. Like, “Oh, f*** yes.” It’s in you as a driver, it’s in your team, it’s in your spotters, it’s in the fans, there’s a flow that circulates and moves around from team to team over the course of the race.

It’s almost like there’s only so much of it to go around. As your race starts to move in the right direction, someone else’s is moving in the wrong direction, and so you’re stealing it from them. It’s not distracting, it’s not giving you a buzz, it’s just something you feel there that you don’t feel in quite that way anywhere else.

That’s what it’s all about. It all comes back to this perfect chaos in the magnitude. The cars are designed to be great at this place, and so you kind of know that it’s in there. The sheer size of the place and the number of people, the fact that it’s on Memorial Day weekend and there’s all this buildup and hype…

SS: The obvious next question is where you’re the one losing that lightning. When the tide won’t turn, no matter how you charge.

JRH: Obviously, I’ve been in some extreme scenarios at Indy. Thinking back to 2011, that sensation, it was all happening right at the end.

SS: You don’t have to rehash that—I can’t imagine how many times you’ve discussed it.

JRH: No, it’s relevant. That would’ve been a lot worse if it had been five laps earlier and I would’ve finished 30th.

If you’re just not in the mix, or not in contention for the win? At some point, you just kind of know. You know it’s going to take some bizarre happenings to get vaulted into the top five. Attitude starts to play a more significant role. All the way up until the start, you know there’s a chance. You know that it might be those couple of clicks of right front compression or whatever, and that’s what you need to get it to feel just how you want.

Regardless of how silly it might sound, I think race-car drivers and athletes must be fairly hopeful people, because we wouldn’t keep showing up to do this kind of thing if we weren’t.

SS: I always liked the theory that holds positive thinking as a form of happy insanity.

JRH: There comes a point where you realize the race is not unfolding in your favor. You can either succumb to the idea that if you’re not winning, it doesn’t matter, or you can just tap back into it: 85 laps left to do the best possible job I can. Fifteenth instead of 16th. If I do that, I’m not going to have to think that hard about what I learned from the whole experience.

SS: Rick Mears told me he always looked at the 500 the same way—the years he won or his first crash there, it was all the same. But most drivers say your perspective changes. Not everyone can be Foyt, run there half a century. And the older you get, the more that sinks in.

JRH: Coming up through the ranks, when the 500 is just another event on the schedule? I didn’t really appreciate it at the time. I certainly appreciated that if you won the race, it could make your career. But not the idea that, for a driver, it was unique.

Eleven years later, it’s the experience of going and qualifying, how much that matters to me. Of understanding how many little things happen out of your control. But also how epic it is when you’re at your best for 500 miles, part of history, in that event that matters so much to everybody. For me, it was realizing that it actually is The Place.

Wanting to be better there is what made me seek out how to be better everywhere, basically. That gravity, that it can single-handedly motivate you, as a driver, to do something different? That might be all you need to know, really.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.