Smithology: A 2002 for 1800, and why

Welcome to The Weissrat Chronicles, Sam Smith’s tale of dragging an $1800 BMW 2002tii back to life in off-hours and weekends, when he’s not busy testing new cars for Hagerty. This is the first installment in the series, with the chapters best enjoyed in order: One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, and Seven. Shorter updates live on Instagram, at @thatsamsmith and the hashtag #weissrat. —Ed.

I have a billion memories. Maybe, one day, I’ll remember most of them.

J.D. Power would call this a problem of initial quality. If the human brain were a car, your narrator’s hippocampus would have left the factory with rats gnawing the wires. It has been like this as long as I can remember. (Don’t think too hard about that last sentence.) Vivid images among fuzz—that time I did that thing, for example! With that person! Or was it that other person? In that place we went?

I got married, once; I remember that. The books on my office shelf have been read, to the best of my recollection. Everything else is suspect. Except, of course, the BMW 2002, a machine I will never forget.

The first one is memorable mostly for how we parted. I was 17, in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1998. The car had been in my life only a few months—a 1974 2002tii, the last year for factory fuel-injection, thick Earl Scheib paint in Fjord over the original metallic blue. Its $3500 sale price absorbed both every penny I had saved and a small loan from my parents. The car was sitting at a stoplight when a Ford LTD walloped it in the face from the oncoming lane. Ford bumper hit left BMW headlight at 40 mph, and physics did the rest.

After the accident, I limped the car to a side street, estimating repair costs in my head. When the cops arrived 30 minutes later, I was sitting on a curb, watching coolant run into the gutter and thinking up sad little limericks using the word “totaled.” The officer who wrote the accident report saw the look on my face and patted me on the shoulder.

“You didn’t get hurt, kid, be thankful. It’s just an old car.”

The report he wrote misspelled the model: 2002tit.

The second 2002, a ’76, popped up a few months after. Zero rust, and a warm shade of orange the factory called Inka. A friend and I were driving past the University of Louisville when I spotted a familiar roofline in a staff parking lot. We stopped, because we were teenagers with nothing else to do. I walked around the car slowly, then lay down on the pavement, eyeballing floors and frame rails, getting mud and grease on the pants my mother had asked me to keep clean.

So many thoughts: Inka — in my silly little town? Does dude know what he has? For sale please for sale. I have some money. Maybe. Just? Blind, unfounded hope. Then butterflies in the stomach as we drove away. I left a note under the wiper. A few days later, I was fishing a Pop-Tart out of the toaster when the owner, a clarinet professor at U of L, called my parents’ house line. Mom handed the phone to me, and the professor threw out a number so close to the insurance settlement on the blue car that I dropped the Pop-Tart. I walked on air for days, as you do when seemingly impossible things happen before breakfast.

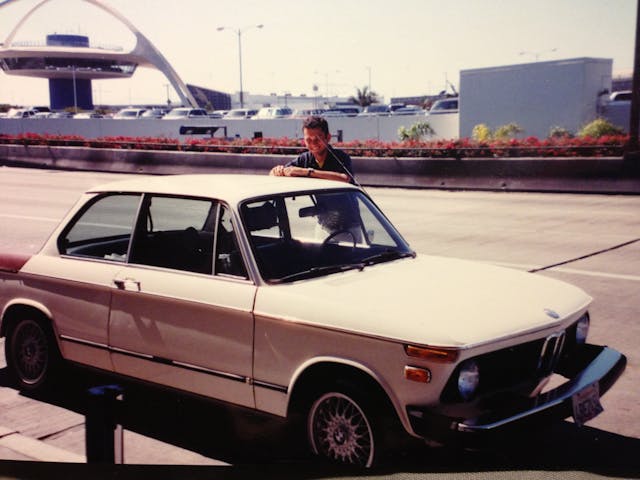

Neither car cost much, because this was the 1990s. Collectors of the time generally viewed the 2002 and its ilk as too pedestrian to be genuinely “interesting,” less sexy than a contemporary Alfa or Porsche. Still, durability and joy had long kept them afloat with the die-hards, especially in dry climates. My parents didn’t qualify as old-BMW die-hards, but I liked to kid myself into believing they did. As newlyweds, they had bought a 1976 2002 new from a tiny dealer in Louisville called Grand Prix Motors. They sold the car while I was still in diapers, but in the summer of 1994, three years before I got my driver’s license, they took me and my sister on vacation to San Francisco, to visit family. What I saw on that trip dented my skull.

Before the Bay Area became a tech-fueled Monaco, San Francisco was a gold mine of daily-driven classics. At 13, dorked for cars and sauntering off a Kentucky plane with a Sony Walkman on my belt, I had no idea what was about to happen. In the 40 minutes it took us to drive from the airport to the Golden Gate Bridge, my mouth gaped so much, my tongue went to sandpaper: A Mercedes Heckflosse sat waiting in the airport garage. Seventies Fords and Chevys dotted SFO’s service roads, common as pigeons. Porsche 356? Have two before you’re out of sight of the airport. Over there, a hydraulic Citroën sitting at that gas station; behind you in Arrivals, a sliding-window Mini, paint dull as pencil eraser. The tally grew as we hit the freeway, the cars equally varied and improbable, a nonstop feed of unlikely accompanied by run-on streams of thought like Is that a Ferrari Dino in traffic why is there a Ferrari Dino in traffic what is happening where are we is this Oz this has to be Oz.

Then the kicker.

Five minutes up the 101, a 2002 barged through traffic, passing us in the left lane with a blinker on. I glanced out the opposite window and saw another dash by on the right, bending into an off-ramp as a puff of smoke left the pipe. (What I didn’t know then: valve-guide wear. Common.) A late one with no bumpers and faded paint hovered behind us for a bit, its toothy little kidney grille and rabbity face smiling at nobody in particular. They kept coming: a third, a fifth, a sixth, too many to believe. On side streets visible from the freeway, below us on overpasses, waiting at lights or in parking lots, anywhere real cars go. And that was the key: To a one, they were less than perfect, not pampered garage queens, real cars obviously used for real driving by real people.

My face smeared into the window. I counted, rattling off numbers aloud, in shock: twenty-five? Thirty. Forty? Forty-five. What is going on? We hit the north side of the city, sat in congestion for a bit near the financial district, then grabbed the ramp out of the Marina, toward the Golden Gate. Climbing the bridge approach, an early 1600 passed us on the right, six-volt headlights a dim presence on the road, then dove back into the city, toward the Presidio.

Forty-six?!?

My face felt red. Probably because it was.

We crossed the bridge. I collapsed back into the seat, exhausted: Forty-six 2002s between airport and bridge, from the city’s southern limits to the water in the north. Google now tells me that works out to 18.8 miles of road, so figure around two-and-a-half 2002s per mile. Forty-six seemed like some kind of gift. I chewed on the number for a moment, trying to suss a reason or some capital-T truth. In retrospect, it was just a happy fluke of circumstance: In the state that rust forgot, old cars fun and durable often miss the chance to die. And in a dense, quirky little city that had yet to excise its middle class or its quirk, known to be a hotbed of imported automobiles for more than half a century, why wouldn’t people gravitate to a practical, cheeky little German box? Especially if it was great to drive and cost next to nothing?

Not that they were always cheap; 2002s were costly when new, especially by the pound, a four-cylinder sedan priced hundreds more than a V-8 Mustang. They sold anyway. BMW moved more than 800,000 examples of its 02-series cars globally from 1966 to 1976. Car and Driver’s David E. Davis, Jr. once called the 2002 “one of modern civilization’s all-time best ways to get somewhere sitting down,” and C/D for decades heralded the model as the blueprint for the modern sport sedan. The car’s success helped re-establish BMW, struggling since the 1950s, as a going concern, and it elevated the brand to industry benchmark in driver feedback, a position only recently lost.

Naturally, I knew none of that at the time. But that day, crossing the Golden Gate, I made a decision, sudden and final, as kids do: The 2002 had to be wonderful. How could it be anything less? It looked wonderful, purposeful and taut. Wasn’t that enough?

Brain damage rarely cures itself. After we flew home from California, I dove into a nascent Internet. Poring through a mailing-list archive, I found a note where some innocent had asked the difference between the 2002 and its Italian contemporary, the Alfa Romeo 105/115. “BMWs are like Alfas,” some wag replied. “Same idea, but the 2002 is sturdier and a little less romantic. If an ’02 wants to get up every day and go to work, the Alfa just wants to lie around and sex you.”

Being a certain age, I got up from the computer, walked to my father’s bookshelf, and dug out a book on Alfas. Dad had once owned a 105 coupe. Then I went into the kitchen, found him making a sandwich.

“You probably shouldn’t live with an Alfa until you’re older,” he said, between bites. Those words made no sense then and make all the sense now. Spectacular cars. I would no sooner have steered teenaged me toward one than given teenaged me a flamethrower.

I remember my friend Seth buying a nearly rust-free ’68 2002 our senior year. He sold what he called “recreational plants” to pay for it. Two weeks in, he almost put the car on its roof, backing into a second-gear downhill right-hander 10 mph too fast. We were listening to The Who’s Greatest Hits, windows down, and I had been wondering what it meant to substitute / me for you. Then we almost broadsided a Buick and my face almost substituted for a GM hood ornament. Because we were in high school, we got a slice of pizza afterwards, and laughed about it.

I remember the happy way an ’02 bats into a corner, the quick but soft settling as that simple Sixties suspension geometry does awful things to a tire. The cars handle well but not uniquely so, always working their front rubber a bit too hard. Their abilities wouldn’t matter if that nerdy little shape didn’t egg you on, seemingly so thrilled to be running: Here, I have this much, take all of it. Plus a roomy back seat and that rock-solid engine, a glassy and seemingly unburstable four. BMW would later take the 2002’s block geometry into Formula 1 and win a title, then use a nearly identical casting for the epic twin-cam four in the marque’s first M3.

In college, I stumbled onto a BMWCCA track-driving school at Gateway International Raceway, outside St. Louis. The $250 entry fee smoked my whole savings account and the brake pads burned down to the backing plates in an afternoon, but I was sunk. That orange ’76 went up on plane in a corner, skimming along on soft springs, forgiving in a slide and almost comically free of vice. Years later, I went club racing, lapped supercars and prototypes and Formula 1 cars as an editor at Road & Track, entered precisely one professional road race (long story), and drove a factory-backed 2002 and a 3.0 CSL in the Monterey Historics. Looking back, none of it seems possible, except when I remember where it started.

Good cars hint at where they can take you. The great ones stick with you years later as a reminder to stop thinking so much and just go already.

When Seth decided to sell the ’68, Dad and I banded together and bought it. Then we stripped the tub and went road racing in SCCA Improved Touring. The car saw a few seasons in the Midwest before I ran out of money and sold my couch to pay for a set of tires. Shortly after that, I ran out of furniture and had to stop racing. Dad still owns Seth’s car; I don’t miss the couch.

I remember the road-racing championship I won. A borrowed car in a modest little California series a few years ago, but a title nonetheless. A crew of 2002-owning friends in San Diego had asked for advice on suspension setup, and that somehow evolved into a ride for a year or three. Hanging out with those people eventually became so much stupid fun that I would have showed up at the track simply to sweep out the trailer.

There were so many more cars and people. Engineless shells towed from here to there. Running projects driven back from the west coast for friends. Track rats and daily drivers on which I was drafted to wrench. To say nothing of the other cars and motorcycles that entered my life because they shared parts with a 2002, or even just reminded me of one, rabbit holes all their own. Machines that did nothing perfectly but everything well, and with gusto.

The volume slowed only as the world wised up—as I grew older, the cars grew too expensive. Or maybe they weren’t too expensive, just once again priced right for what they deliver. Either way, they were no longer affordable enough to be viewed as cast-offs or punky little social rejects. The mental disconnect between the car’s personal meaning and its cost grew too great, and my writer’s salary remained too modest to justify a nice example. I moved on to other things.

It’s both comforting and not when a privately cherished object becomes Instagram-famous auction fodder. Fifteen years ago, a friend connected me with a clean 2002 Turbo for sale—the rare, 170-hp factory hot rod, and one of the first turbocharged production cars in history. The seller wanted $15,000, around five times the price of a good 2002. I passed. If you want that Turbo in 2020, add a zero; 15 grand these days will get you an okay tii, rough around the edges. Ordinary 2002s no longer dot streets in San Francisco or anywhere else. Now mostly saved for Sunday drives and garage queening. A little German box that begged to be used every day, essentially retired, the cheap ones gone.

Except when they aren’t.

This one found me. We’ll discuss how another time. For now, just know that the $1800 stack of 1972 oxide in my shop is a very early 2002tii, the 70th example built for America. If that price sounds like a knockout, know that I nearly passed out when I looked under the car. The rear subframe mounts are vapor, rusted out of existence. The rockers are gutted, the shock towers split open. From the floors to the roof, not a single panel is free of holes or significant rust, every trap the cars are known for. The thing moves under its own power, but real mileage would be suicidal. No humane individual would leave this collection of hurt alone with small children, or a lady, or even a politician.

I couldn’t say no.

Piles like this present a few options. The sensible path would be to part the car out. You could also restore it, grinding and welding the body whole, years of labor to save little more than a transmission tunnel, a firewall, and a VIN. Finally, you could shell-swap it, bolting the mechanicals and trim onto an uncorroded tub.

For various personal reasons, those options now seem, in order of appearance, cruel, financially insane, and boring as toast.

The tii’s previous owner, an elderly gentleman, drove the car for decades. He retired it about ten years ago, rust finally too thick. Our agreed price was far less than the car’s value in parts. He handed me the keys. An obvious kindness, nearly free.

As I loaded the car on a trailer, he smiled softly, eyes distant.

“I hope you fix it,” he said, “and drive it.”

The look on his face reminded me of something. Or maybe just someone I knew a long time ago. This kid on a curb.

So I came up with a plan.

To be continued.