Music For Your Road, no. 4: It Plays Like A Steinway!

If German immigrant Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg had only gone whole hog (oder, ganzes Schwein) when he Anglicized his first and last names upon arriving in America in 1850, today, the world’s most famous piano would be known as the “Stoneway.”

Or, the “Stonepath.”

Or (my favorite), the “Stonestreet.”

For better or worse, the Anglicization was not total. The pianos Steinway and his sons made in America have been and will be Steinways, not Stonepaths.

Along with Einstein and Heifetz, “Steinway” is a family name that is also a common noun, as in, “A Heifetz, he is not.” Or, “It plays like a Steinway!”

Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg was an amazing character. He was born in the late 1700s. While still a teenager, he served in the army of the Holy Roman Empire in the pushback against Napoleon’s occupation of parts of Germany.

Upon leaving the army, Steinweg apprenticed to an organ builder, discovering in himself a love of music as well as an aptitude for fine craftsmanship. Because of strict Guild rules (his status was apprentice, not master), Steinweg began building instruments in secret—in his kitchen.

(Building instruments in secret—in a kitchen—really makes me think of Hermann Hesse’s Medieval novel Narcissus and Goldmund. Miles Davis hated that book, but I love it. Perhaps you will like it, too!)

The first instruments Steinweg built in his kitchen were zithers and guitars. He then moved up to pianos, starting with small pianos, later increasing their sizes, learning and thinking all the time. Still working in his kitchen, he built his first grand piano in 1836. That piano is now in New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1839, Steinweg pocketed his first Gold Medal, awarded by a state trade exhibition in Braunschweig. At some point, given the restrictions of the Guild system (as well as the state of politics in Germany after the uprisings of 1848), Steinweg concluded that there would be greater opportunities for him in the United States.

In 1850, he emigrated, with several of his sons. Steinweg modified his first and last names, and went to work for other New York City piano builders until he had amassed enough experience (and money) to start his own company, in 1853.

During the early years of Steinway & Sons, Steinway’s innovations gave the modern grand piano its mechanical and tonal identity. About half of Steinway & Sons’ 139 patents were granted to the first and second generations of the family. For instance, Steinway & Sons invented the middle (“sostenuto”) piano pedal.

Steinway continues to innovate. Steinway’s hot product these days is a computerized-playback grand piano, the Steinway Spirio; it is controlled by an Apple iPad app. The Spirio system works by true motion capture, not just on-or-off “key punch-ing.” The software is so sophisticated (and the datasets that are being managed are so granular) that you can even use the iPad app to change the volume at which the Spirio plays back a digital file. (For those intimate cocktail parties, I guess.)

The library of playback performances available from artists such as Lang Lang, Yuja Wang, Aaron Diehl, Billy Joel, Jenny Lin, Pablo Ziegler, and Bill Charlap now includes more than 2,000 musical selections. New tracks are available every month.

The photo at the top is of a limited-edition reissue of a piano, the case of which was designed by famed Mid-Century-Modern architect Walter Teague for Steinway’s 100th anniversary, in 1953.

Today’s “Teague Sketch 1111 Limited Edition” is priced circa $132,000; and, of course, it is a Spirio reproducing piano as well. It might make a memorable “just-because” present!

Here are 12 piano recordings of great merit. Eight of them are on the Steinway & Sons’ label. The other four similarly are Desert-Island-Disc-quality offerings both old and new, from other labels.

1. Cole Porter on a Steinway (vol. 1): Jed Distler, Simon Mulligan, Adam Birnbaum

Three wonderful pianists take turns here, offering solo-piano treatments of 12 Cole Porter songs, from 12 different Cole Porter musicals. Think about that for a moment—most musicals that come to mind are collaborations between a composer and a lyricist; but the composer Cole Porter was his own lyricist.

At Yale, Porter minored in music, and was one of the first members of Yale’s legendary a-cappella singing group the Whiffenpoofs. Most remembered for his witty, urbane lyrics (which frequently contained in-jokes and double entendres), Porter was nonetheless a composer of accomplishment. In fact, he briefly studied composition at the Schola Cantorum in Paris, under Vincent d’Indy. Of course, by that time, Porter had already written 300 songs—while still a student at Yale.

2. The Goldberg Variations (J.S. Bach): Beatrice Rana

The piano is a percussion instrument. A pianist presses down on a key, and a complicated mechanism flips a felt-wrapped hammer upward until it hits (usually) two or three strings that are tuned to the same note. The piano is a percussion instrument; just get used to it.

And therein lies the challenge in making music on a piano—creating the illusion that one note just flows into another, as is the case with the human voice, or the violin.

Furthermore, the piano’s dynamics are a one-way street. Once you hit a note, it only can die out—there is no way to “swell” the volume of a sound, once a note has started sounding on the piano. Whereas, swelling a note is part of a singer’s stock in trade, and a violinist’s too.

J.S. Bach’s “Goldberg” variations are a cornerstone of the piano repertory, and an important part of everyone’s shared cultural heritage. I think that, in the 1950s, if people owned one jazz LP, it would have been Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue; and if they owned one classical LP, it would have been Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations. Or, at least the sales figures suggest so.

Beatrice Rana’s recent (2017) studio recording has become my favorite piano version of the Goldbergs. Her “singing lines” in the Aria (and elsewhere) are joys to behold. This is a thoughtful (but not overcautious) interpretation, from a young pianist who seems to have no limitations whatsoever when it comes to technique. And, she has fascinating musical insights.

3. Watercolor: Shen Lu

All the nice pianistic things I just said about Beatrice Rana apply in full force to Shen Lu. Mr. Shen plays like a mature artist who understands the music, and whose technique is effortless. Watercolor is a recital that bookends familiar masterpieces of 20th-century Western piano music (Ravel’s Miroirs, and Rachmaninoff’s Op. 33 Etudes-Tableaux) with piano music by Chinese composers Chen Peixun and Tan Dun.

It is in Rachmaninoff’s Etudes-Tableaux that Shen shines most brightly, I think—in particular, No. 3 in C minor. There is a plangent quality to the slow upper-octave melody in the middle section. I think that’s the kind of thing many of today’s hot-rodding young pianists don’t seem to be able to put across. By the way, this is one of the most gorgeous-sounding piano recordings I know of.

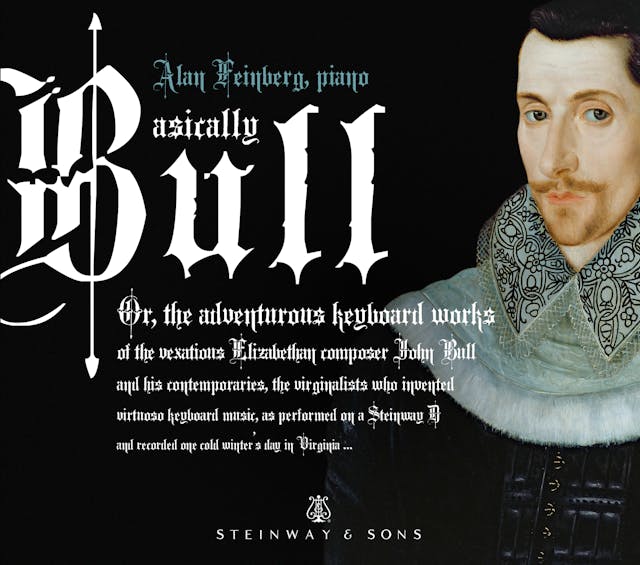

4. Basically Bull: Alan Feinberg

This survey of very early English keyboard music (some of the scores date back to 1611) originally composed for the instrument called “the virginals” should not “sound right” on a modern Steinway concert grand piano, but it does! (The most-represented composer is John Bull, hence the sophomoric wordplay of the title.) Comparisons to Glenn Gould and André Watts are not out of line.

When Basically Bull was a new release, I praised it to the skies in Stereophile magazine, concluding, “Even if the last solo-piano recording you really enjoyed was George Winston’s December, I think you’ll love Basically Bull. Highly recommended.”

5. The French Suites (J.S. Bach): Sergey Schepkin

Bach’s French Suites might not be as household-name familiar as the “Goldbergs,” but they are immensely treasureable as well. Sergey Schepkin graduated summa cum laude from the St. Petersburg Conservatory, but he now lives in Boston. His Bach keyboard recordings of 20 years ago are still sought-after by audiophiles. More recently, he has begun re-recording that repertory. Thoughtfulness, loveliness, and a sense of discovery abound in this generous collection, which, in addition to the French Suites, features performances of two Fantasias.

6. Mélancholie: Zhenni Li

Zhenni Li was born in China, but educated at Juilliard, Yale, and McGill. Britain’s authoritative music magazine Gramophone hailed this, her début recording on Steinway’s house label, as “A bolt from the blue.”

However, her program does not start out that way; it starts with Arthur Lourié’s Op. 1 Préludes fragiles, which live up to the album’s title of “melancholy.” The major work is Schumann’s far-ranging first piano sonata. Zhenni’s interpretation is self-confident yet sensitive; her technique is prodigious; and her sound is simply grand.

7. Siegfried Idyll: David Deveau

Richard Wagner was not a nice man. He was both a wife-borrower, and a wife-stealer. He stole Franz Liszt’s daughter Cosima away from her husband. Cosima then gave birth to Wagner’s only son, Siegfried. Wagner wrote his Siegfried Idyll (for 13 instruments) as a birthday present for Cosima. It is heard here in a piano transcription.

This engrossing program begins and ends with works by Franz Liszt. The first track is Liszt’s “Funérailles,” for the revolutionaries killed in 1848. The program ends with Liszt’s “At the Grave of Richard Wagner” (1883), which, while quoting Wagner’s last completed opera Parsifal, veers off in the direction of atonality, toward the vista of cosmic emptiness that appears in Mahler’s last symphonies. Bookended by the Wagner and Liszt pieces, there is a lovely selection of Brahms caprices and intermezzi. David Deveau’s pianism is stellar, and the recorded sound is second-to-none.

8. Get Happy: Jenny Lin

Jenny Lin’s ambitious, technically demanding program consists of virtuoso arrangements of 17 Broadway show tunes, plus one movie theme. Lin’s playing positively sparkles. If this recording doesn’t put you in a positive mood, try pouring a glass of champagne! (Cole Porter, I am sure, agrees with that.)

Cole Porter’s scores are—of course—represented (by “Begin the Beguine” and “So in Love”). Also heard from, are Richard Rodgers, Irving Berlin, Harold Arlen, and George Gershwin.

But for me, the standout piece (and the most impressive performance) is Marc-André Hamelin’s Meditation on “Laura,” i.e., David Raksin’s theme music from Otto Preminger’s 1944 mystery-thriller film. Fascinating chromatic twists and turns mirror the film’s plot (or, at least I think they do).

9. Solo: Pablo Ziegler

Pablo Ziegler is an Argentine composer and pianist, best known in the US for the decade-plus he spent as one of the sonic and musical anchors of Astor Piazzolla’s revolutionary “Quinteto Tango Nuevo.” This solo recording displays Ziegler’s full-bodied tone, fearless virtuosity, and completely committed musicianship.

For me, the standout track is “Oblivion,” Piazzolla’s elegiac interlude from the soundtrack to the film version of Pirandello’s “Theater of the Absurd” play Henry IV (meaning the Holy Roman Emperor).

10. Good Night: Bertrand Chamayou

“The lullaby’s place is halfway between dream and reality,” writes French pianist Bertrand Chamayou. “There is that special moment as you are falling asleep, and you experience all kinds of emotions.”

This wonderful collection brings along modern and contemporary composers as companions to Dr. Brahms. A great gift for the parents of young children; or, for anyone who might appreciate some 100%-organic music. A fantastic recording job, by the way.

11. Emanuel Ax plays Chopin

Recorded in 1975, this remains one of the most beautiful records of anything ever made.

(I think that just about covers it.)

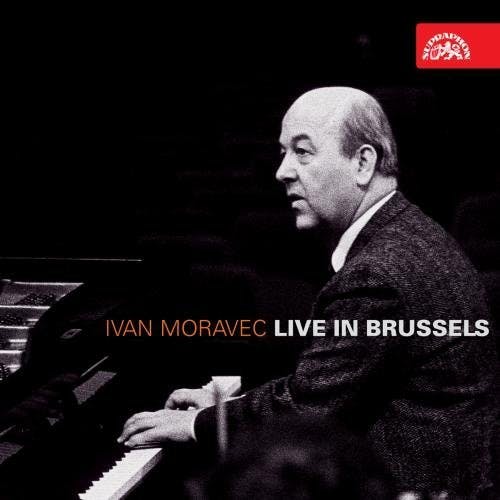

12. Live in Brussels: Ivan Moravec

Ivan Moravec (1930-2015) was the ultimate “pianists’ pianist.” Moravec’s playing was not flashy. His repertory was not huge: he largely stuck to the “undeniable greats” (such as Chopin, Debussy, Beethoven, Mozart, and Brahms), and a few Czech composers. Moravec rarely visited the US. He never recorded for any of the “top” record labels.

However, the astonishing extent to which Moravec could control the smallest movements of his fingers (coupled with his extraordinarily deep musical understanding) translated directly into revelatory performances of those works he chose to play. This live recording from 1983 is the best introduction I know of to his art.