Malibu Grand Prix: When pint-sized cars were a big-time attraction

Malibu Grand Prix.

For wannabe racers of a certain age—uh, that would include me—these three magical words granted entrance to a motorsports nirvana where we could indulge the fantasy that we were Mario Andretti reincarnate, one 55-second lap at a time.

At its peak in the 1980s, the Malibu Grand Prix empire encompassed close to 50 tiny racetracks across the United States, Canada, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Hundreds of thousands of racers racked up millions of laps at a buck-or-so a pop as we chased after ever-better times posted on the electronic timers just beyond the finish line. Devotees with treasured Malibu Grand Prix licenses included not just dweebs and wankers—again, like me—but celebrities such as the teenage Leonardo DiCaprio, the adult Tupac Shakur, and the totally addicted Paul Newman.

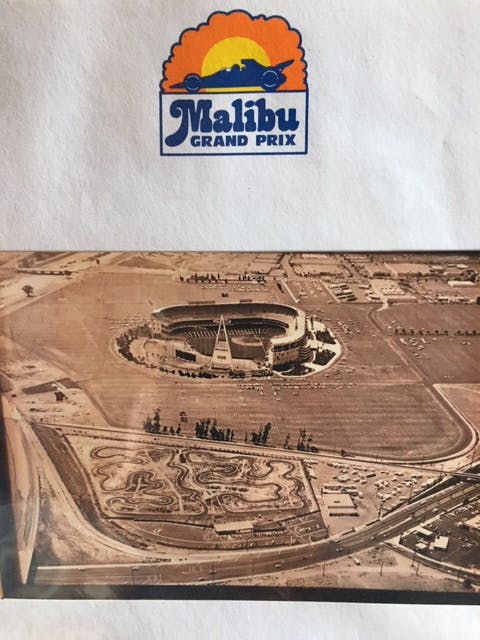

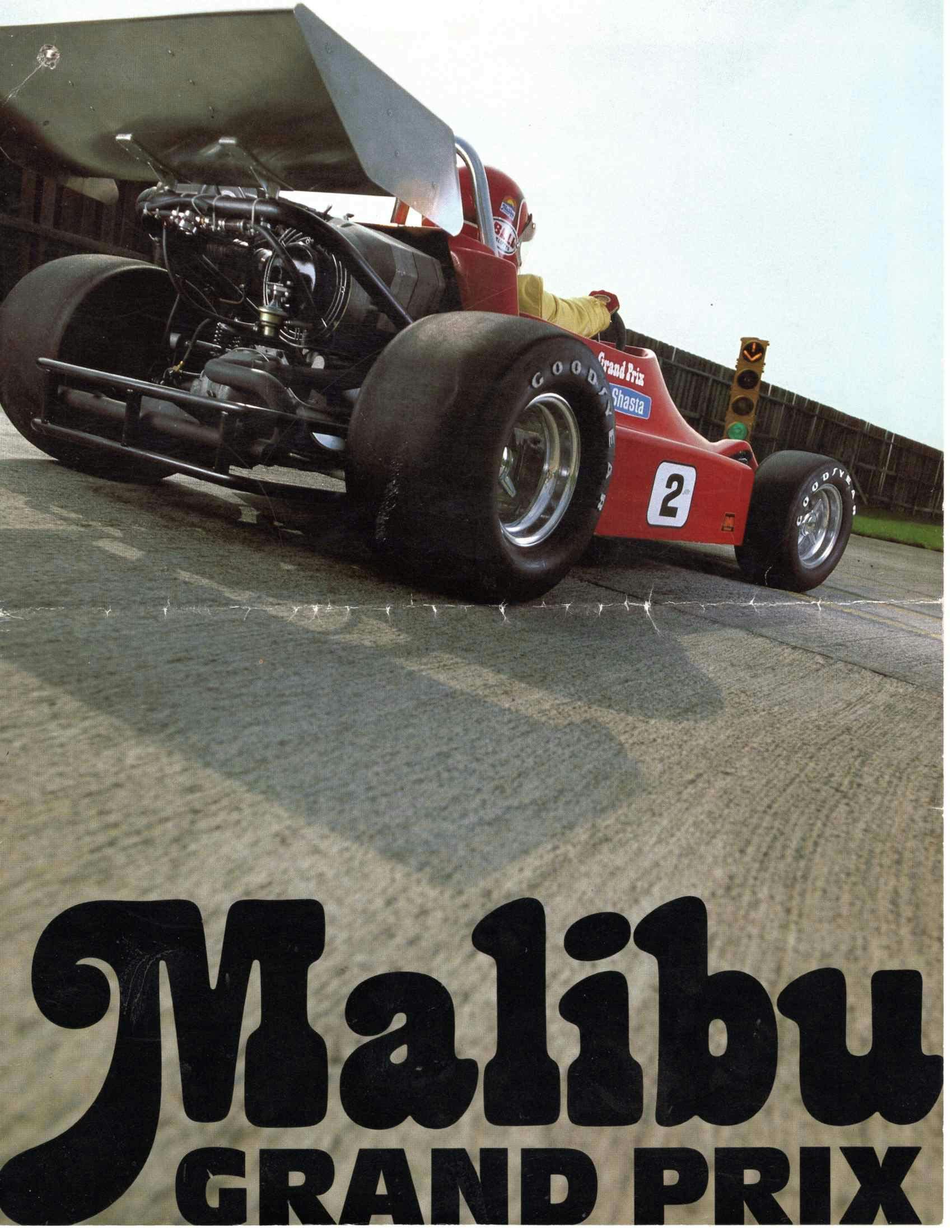

When the first Malibu Grand Prix opened in the parking lot of Anaheim Stadium in southern California on a Friday morning in 1975, there was a line of customers waiting to get in. More than 15,000 people sampled the faux-Formula 1 cars during the first week. Almost every middle-age racer I know logged seat time at Malibu Grand Prix. Not just poseurs but even guys who grew up to be big-name pros.

“When I was a kid, every time we drove past the Malibu Grand Prix on the 210 Freeway, I would go, ‘Oh my God!’ I couldn’t believe how cool it was,” says four-time Trans Am champion Tommy Kendall. “As soon as I turned 16 and got my driver’s license, I started spending every spare penny I had at Malibu Grand Prix. Later, when I was driving the Malibu Grand Prix car [a Mazda RX-7 in professional IMSA competition], I would get this stack of tickets sent to me in the mail, and I couldn’t believe I was getting free laps at my favorite place on earth.”

Looking back, the Malibu Grand Prix impulse seems less like a dream than a delusion. Although the cars were billed as scaled-down F1 thoroughbreds, they were nothing more than clunky, oversized go-karts with fancy fiberglass bodywork. Notwithstanding the aspirational rear wings and slick tires, the short circuits and serpentine layouts capped top speeds at about 40 measly mph. Wheel-to-wheel competition was strictly prohibited, and drivers had to come to a complete stop—and hand over a pre-purchased ticket—before starting another lap.

Whenever I wax poetic about the glories of Malibu Grand Prix, young racers gaze at me with a wordless eye roll reserved for old fogeys on a pathetic nostalgia trip. You spent all that time and money on what? Of course, hindsight is 20/20, and every new generation loves to sneer at the foibles of the one that preceded it. Before dismissing Malibu Grand Prix as a pitiful form of boomer cosplay, however, consider the amateur road racing landscape circa 1975.

At the time, the only game in town was the SCCA, a.k.a. the Secret Car Club of America, notorious because it was so small and so hard to get into. NASA hadn’t yet popularized the track-day format. Entry-level series such as the 24 Hours of Lemons or ChampCar didn’t exist. There was no iRacing or Gran Turismo. The first blockbuster coin-operated racing game—Pole Position, which depicted Fuji Speedway in blocky graphics—wouldn’t debut until 1982.

Then, as now, full-on race karts offered the best bang for the buck. But owning and racing a kart was a time suck and a money sink, whereas Malibu Grand Prix offered a clean and painless arrive-and-drive experience. More to the point, karts looked like clown cars and sounded like lawnmowers run amok. The genius of Malibu Grand Prix was that, if you squinted just right and indulged in a little magical thinking, it was possible to convince yourself that you were a legitimate race car driver at the wheel of a proper little F1 machine.

Okay, so I was an idiot. I wasn’t the only one.

The first man to make a modern, good-faith effort to bring racing to the masses was serial entrepreneur Malcolm Bricklin. As usual, he was long on vision but short on execution. Bricklin tried to franchise a concept he dubbed FasTrack. The idea was to let amateurs race unsold (and unsellable) Subaru 360s wearing funky fiberglass bodies designed by Bruce Meyers of Meyers Manx fame on an off-road track delineated by pylons and stacks of tires. The concept barely got off the ground in 1970 before ending up six feet under, with Bricklin losing a $2.39 million breach-of-contract lawsuit.

Credit for creating what would later become the Malibu Grand Prix paradigm—autocross-style competition in full-bodied, open-wheel car-like go-karts—belongs to the DeLorean brothers, John and Jack. In 1973, the DeLoreans launched Grand Prix of America with cars designed and built by two prominent ex-Chevy Racing engineers and striped by John Schinella, best known for the “screaming chicken” hood decal on the 1973 Firebird. Investors included Johnny Carson, and the operation was run by Pontiac racing legend Herb Adams.

“Herb hired me to finish the car’s development so we could build 300 cars for the first 20 tracks,” says Harry Quackenboss, who served as chief engineer. “The vision was to eventually have 1000 tracks. John tried to get GM and companies like Burger King interested. But he was having trouble selling franchises and raising money.” Although a couple of tracks were built, Grand Prix of America fizzled as DeLorean shifted his focus to his ill-fated gullwing sports car.

A host of start-ups materialized to fill the void. Mario Andretti briefly went into the mini-race car business with cars fashioned by Indy car builder Eldon Rasmussen. Sprint car ace Don Edmunds, Trans Am veteran Ronnie Kaplan, and even Lola Cars got into the act, delivering 121 undersized T506 and T506B race cars with fully independent suspensions, rack-and-pinion steering, and leather-wrapped steering wheels out of a Formula 5000 car. The boom was big enough to generate feature stories in not only Car and Driver (“Tacos, Pinballs Machines, and Tiny Race Cars”) and Road & Track (“The Walter Mitty Racers”), but also Time (“Le Mans for the Masses”) and Sports Illustrated (“Flat Out in a Wee Grand Prix”).

Even now, it’s not clear exactly what was in the secret sauce that allowed Malibu Grand Prix to thrive while its rivals DNFed. Maybe it was the relentless promotions and over-the-top advertising. (“Ever wondered what it’s like to strap yourself into a high-powered Formula race car and prepare to hurtle around a twisting, turning road course at maximum speed?”) Maybe it was the decision to require a valid driver’s license, which kept kids off of the track and conferred a measure of grown-up gravitas on the experience. Or maybe it was just the name and logo, which traded on the glamour of F1 and the sun-splashed hedonism of Southern California.

Malibu Grand Prix was the brainchild of Ron Cameron, who’d earned his first million in the stock market while he was still in college. Like a lot of rich young men, Cameron amassed a collection of high-performance toys—boats, bikes, and sundry off-road vehicles—that constantly needed attention, so he hired a moonlighting Pasadena firefighter, Jack Long, to maintain them. A Wall Street Journal article about Grand Prix of America encouraged Cameron to consider opening a track of his own, and he asked Long if he could build a viable car.

“I can build anything,” Long said. “But what are you going to do about getting gas?”

This was during the fuel crisis, when cars idled for hours at gas stations. But Cameron wasn’t worried. “Hell,” he said, “they’ll be having so much fun, they’ll bring their own gas!”

Cameron put together a prospectus and had no trouble finding investors. “Ron had one of those dynamic personalities,” says David Bursteen, who joined the company a year after it opened and eventually rose to vice president of marketing. “He could get anybody excited about anything.” To seal the deal, Cameron arranged test drives along the circular driveway in front of his mansion in Malibu.

Cameron raised $250,000 in seed money from local businessmen and leased space in the parking lot of Anaheim Stadium, home of the Los Angeles Angels baseball team. He then commissioned Long to design a car to be built in the nearby shop of Bill Stroppe, who ran Ford’s West Coast racing operation. After the initial production run of 24 cars, Long set up a dedicated Malibu Grand Prix operation in Anaheim and, later, a much larger one in Woodland Hills, where a crew of 20 cranked out hundreds of cars.

Over the next four decades, Malibu Grand Prix would be repeatedly resold, reshaped, and rebranded. Along the way, the company developed new cars and collected a ragtag menagerie of models from failed racetrack franchises. Cars were later modified as components broke, suppliers changed, and tastes shifted. Today, all of these mismatched cars are often grouped generically—and misleadingly—under the Malibu Grand Prix umbrella.

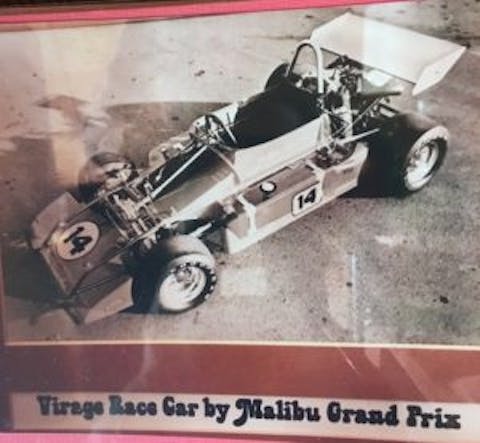

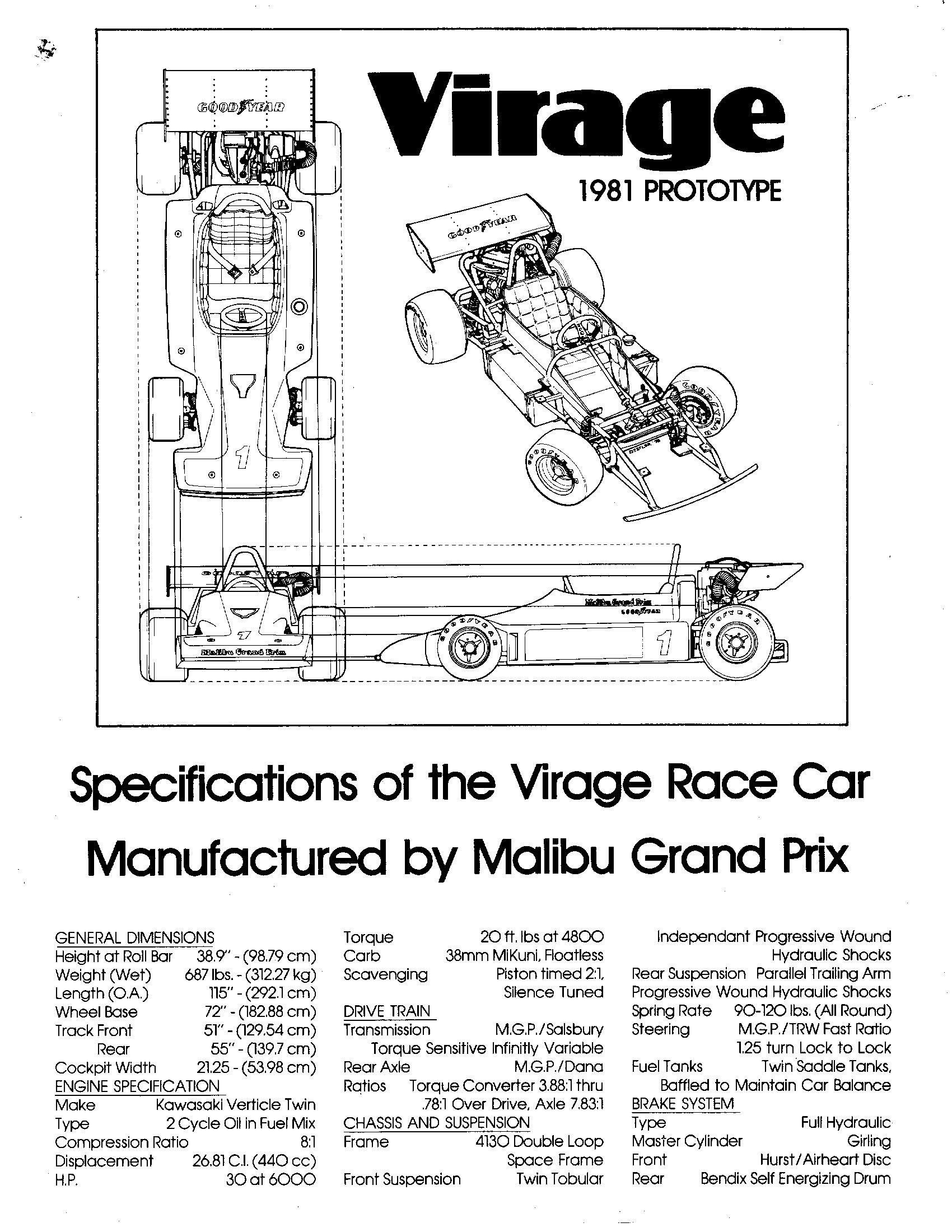

The original Malibu Grand Prix car was dubbed the Virage—a sophisticated name (meaning “curve” in French) for a workmanlike but robust piece of shade-tree engineering. Although the general idea was to create a car that looked like a two-thirds-scale version of an F1 or Indy car, Long’s primary concern was making sure it could withstand what promised to be brutal wear and tear, so the Virage was based largely on proven technology and built like a tank.

A conventional ladder-type frame fabricated out of round 4130 chromoly tubing served as a stout foundation. The front suspension was inspired by the twin I-beam layout found on Ford F-Series pickups, while the rear end featured a live axle located by trailing arms. Long went with discs brakes at the front and drums at the rear. Although the tractor-style worm-and-gear steering was vague, Goodyear slicks mounted on 10-inch wheels generated unexpectedly impressive cornering loads.

The drivetrain was built around a single-rotor Fichtel & Sachs rotary engine that, like the drive belts, were often used in snowmobiles. (Later, it was superseded by slightly more powerful and much more reliable two-stroke and then four-stroke motors.) The Dana rear end incorporated a centrifugal clutch typically found in golf carts. With a hammerhead nose and a large, freestanding rear wing, the fiberglass bodywork resembled the Formula 1 March 751 car and A.J. Foyt Coyote Indy car of the day.

The Virage weighed roughly 650 pounds and made 28 horsepower, which translated into a decent power-to-weight ratio. To minimize risk, Long limited speed in two ways—first, by creating serpentine circuits with no extended straightaways, and second, by designing the Ackerman steering geometry to promote understeer. Lot and lots of understeer.

“Every car was different, but all of them pushed like pigs,” says my friend Tommy Browne, who used Malibu Grand Prix to transition from motocross to race cars. “So what you’d do was stick seat cushions behind you to push you forward in the cockpit and get more weight on the front wheels. That worked so well that I tried stuffing pillows on each side of my legs so I wasn’t flopping around the cockpit. When I got out of the car, my leg was numb—for two weeks! Turned out I’d pinched my sciatic nerve.”

Thanks to its tight performance window, the Virage was surprisingly tricky to drive quickly. “You had to know how to pick the right car,” Kendall says. “Some of them had bad clutches. Some had better brakes. Because of the suspension travel and the open diff, you couldn’t pitch the car like a go-kart, and if you overdrove it like a race car driver, you’d be slow. It was tough for the open-wheel guys. I think my showroom stock experience really helped.”

Setting a quick lap time required talent, technique, determination, and seat time. Lots and lots of seat time. For hard-core would-be racers with no other outlet, Malibu Grand Prix became an obsession. (Ask me how I know this.) There are plenty of stories of guys—and they were always guys—spending $1000 a month, looking for elusive tenths of seconds.

Barry Goldstein was a thirtysomething CPA when he got hooked. “I would leave work early—I was the boss, so that was easy—and I’d drive 30, 40, 50 laps before I went home to eat dinner,” he recalls. “There was a special car they’d pull out for me, and I had a custom fiberglass seat that they would fit in the cockpit. I probably did, on average, 300 laps a week.” Today, Goldstein tracks a Porsche Cayman with a built 3.8-liter 911 motor. But his claim to motorsports fame is that he used to hold the lap record at the Malibu Grand Prix in Northridge.

Malibu Grand Prix was a huge success from the moment it opened in 1975. “It was chaos,” Long recalls with a chuckle. Business was so good that he had to bring in extra people—including a bunch of off-duty Pasadena firefighters—to work 24/7 just to keep the cars running. New outposts opened soon afterward in Fountain Valley, Northridge and Pasadena, and customers kept stacking up.

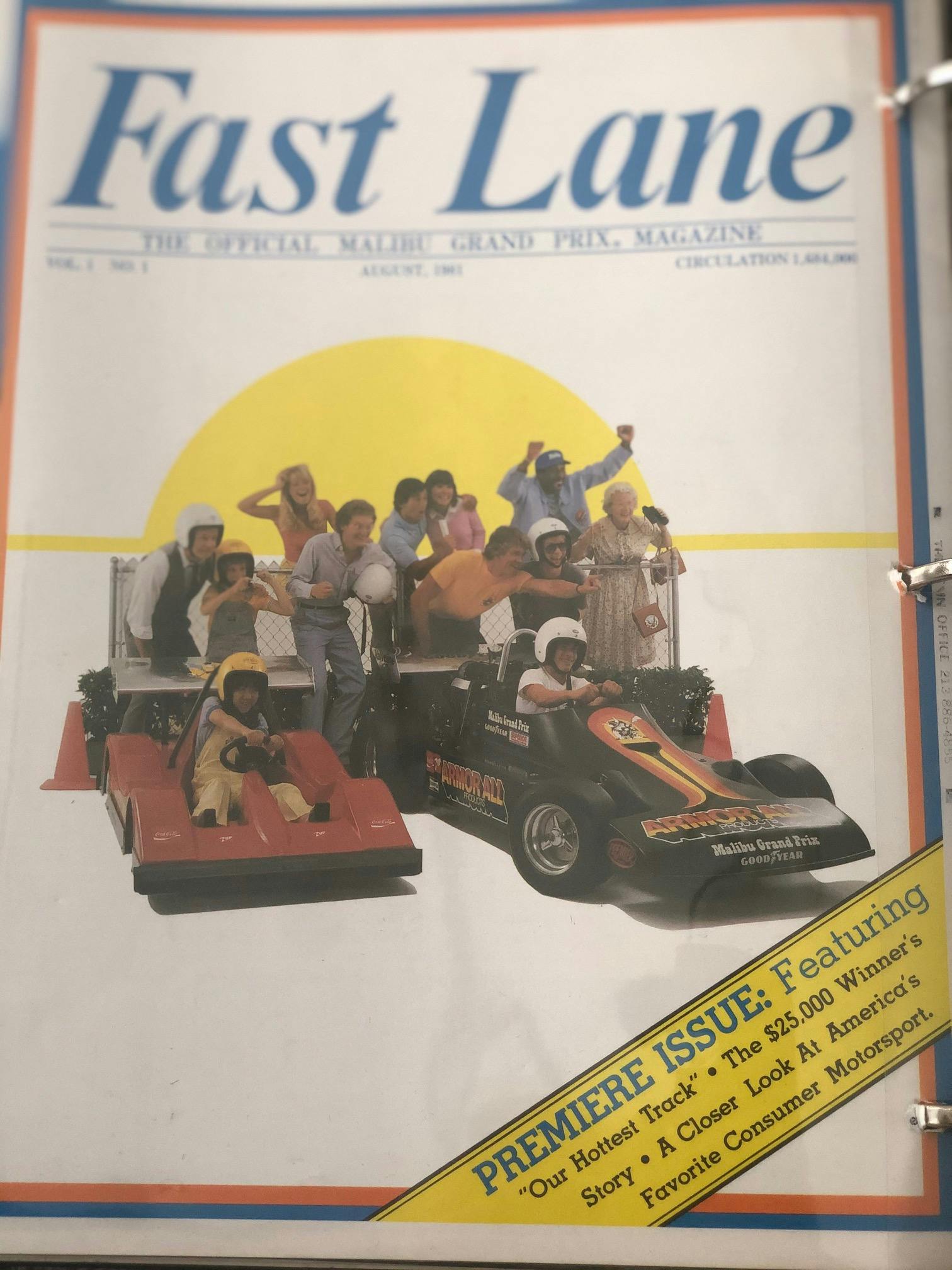

Cameron realized he was sitting on a gold mine. “Ron came up with the idea for buying video games so they’d be spending money while they were waiting to drive the cars,” Long says. Looking back, this seems like a no-brainer. But you’ve got to remember that video games were in their infancy, and arcades for computer games hardly existed. Cameron bought so many coin-operated arcade games that Warner Communications, which owned Atari, acquired Malibu Grand Prix in 1977 and embarked on a $30 million expansion.

Long says 30 additional facilities were built by the time his employment contract ended in 1981. Warner broadened the reach of Malibu Grand Prix by creating so-called family entertainment centers with other attractions such as miniature golf, batting cages, and water slides. A longer-wheelbase two-seat Grand Virage was introduced, and kids were allowed to compete in a Putt-Putt-style kart dubbed the RoadRunner or Mini-Virage. Also, clicking off consistently fast lap times in a Virage unlocked a unicorn known as the Club Car, upgraded with a tuned pipe.

In 1983, the Houston facility was the site of the grisly killing of four employees, a crime that earned local notoriety as “the Malibu Grand Prix murders.” Later that year, Warner sold Malibu Grand Prix to a company led by Ira Young. Besides being a mega-successful Canadian real estate developer, Young was a major-league racing enthusiast. He immediately bought the Mazda RX-7 that Jim Downing had driven to an IMSA GTU championship and festooned it with Malibu Grand Prix graphics designed by his new pro driver, Jack Baldwin.

Young was the platonic ideal of the gentleman driver—extremely wealthy, extremely pleasant, and extremely slow. He would start the endurance races and hand off the car to Baldwin. “I always had to come from way back to win,” Baldwin recalls. Nevertheless, Baldwin notched a pair of GTU championships in the Malibu Grand Prix car. It was then sold to Clayton Cunningham and entrusted to an unproven UCLA business major named Tommy Kendall.

Kendall was a propitious choice. Besides being on the cusp of stardom, he was young enough to have been a Malibu Grand Prix junkie himself, pounding out laps with his neighbor, Jeff Krosnoff, who later raced Indy cars. “One time, I waited until I was down to my last ticket,” Kendall recalls. “When Kroz when out to start his lap, I bombed through the grass and passed him, and he chased me all the way to the checker. Well, the attendant only saw the last half of the lap, when we were racing wheel to wheel, and Kroz got ejected.”

Kendall won two more GTU championships in the Malibu Grand Prix Mazda, making it the winningest chassis in IMSA history. By the time the car was retired in 1989, the Malibu Grand Prix concept was as outdated as Kendall’s RX-7. The 1990s brought the popularization of track days, Spec Miata, and console and PC racing games. With the 2000s came the 24 Hours of Lemons, iRacing, and indoor karting. The remaining properties were sold in 1994 and again in 2002. Since then, virtually all of the Malibu Grand Prix outposts have been shuttered, and even at those few locations where the name is still used, the company’s original DNA—and cachet—has long since vanished.

Randy Davis, who spent 17 years with the company (and who autocrossed a radically modified Virage) estimates that nearly 1000 Malibu Grand Prix cars were built. Over the years, they were upgraded with beefier roll bars, four-wheel disc brakes, rack-and-pinion steering, and marginally modernized bodies. Although most of the cars were destroyed as outposts closed, survivors occasionally are listed for sale on specialty forums and websites like Bring a Trailer and Barn Finds. Greg Prusa is a Malibu Grand Prix fanboy—“I just loved the hell out of it,” he says—who owns three Virages and a Lola T506, and he’s undertaken a ground-up restoration of one of the Malibu Grand Prix machines. “I’ll have upward of $20,000 in it by the time I’m finished,” he says.

When I ask what he plans to do with his cars, he says he’s thinking of creating a private racetrack on his property. Considering where he lives, I guess that would make it the Hiram (Ohio) Grand Prix. David Bursteen, the company’s former VP of marketing, has an even more ambitious idea. “You know those Bird electric scooters that everybody’s using?” he says. “I think that if they had a better body style—like a little formula car—people might use them for local transportation. So it would be the original Malibu Grand Prix concept with a different application.”

An around-town Virage EV? In my mind’s eye, I suddenly see swirling packs of brightly colored, full-bodied, open-wheel, wings-and-slicks scooters zigzagging along the boulevards and sidewalks of Los Angeles. It’s as if the entire city has been repurposed as a street circuit, and the morning commute has morphed into a points-qualifying grand prix. Sounds crazy, I know. But no crazier than Ron Cameron’s original vision of a faux-Formula 1 car that would be every bit as popular as the real thing.

Mr. Virage goes to Topeka—or doesn’t, as the case may be

Randy Davis was a racer. The Virage was a race car writ small. So he decided to take one off the Malibu Grand Prix reservation and set it free on a full-sized racetrack.

Davis—who spent 17 years traveling all over the world supervising Malibu Grand Prix operations—started with a Virage, hacked 200 pounds out of the chassis and fitted the car with a 550-cc Yamaha modded with twin Mikunis and a tuned pipe. The result was nearly 80 horsepower in a 400-pound car, which made it a monster in SCCA autocross competition.

“It was a handful to drive with that short wheelbase,” Davis says. “It would jerk the front tires off the ground if you got on it too hard. But it had so much grip that you could hardly break it loose.”

Davis acknowledges that the Virage was outclassed at the national level, but he terrorized the Solo 2 competition in regional autocrosses. While plenty of prime-time pro drivers clicked off plenty of laps in Malibu Grand Prix cars, Davis had all of them covered.

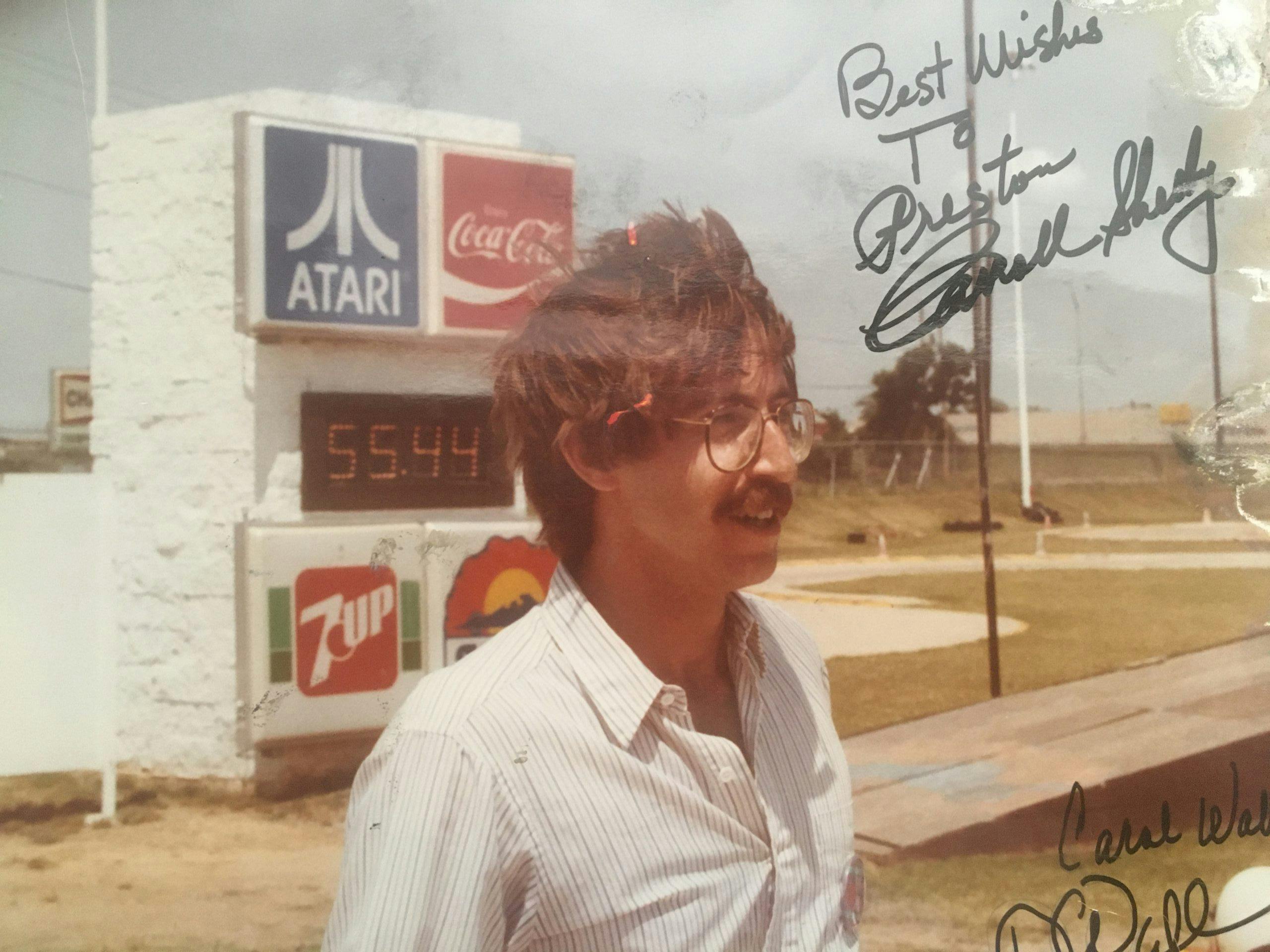

Preston’s greatest race, as witnessed by Carroll Shelby

I’ve driven in hundreds of SCCA and NASA races over the past 25 years. On very rare occasions, I’ve even managed to win a few. But the greatest moment of my motorsports “career” came courtesy of Malibu Grand Prix.

It was 1984. Shortly before the inaugural Formula 1 Dallas Grand Prix, a media race was staged at the nearest Malibu Grand Prix outpost. When my name was called, I happened to be talking to Carroll Shelby, who was serving as the F1 race marshal. “Excuse me,” I told him mock-heroically. “I’ve got to go win this race.”

Full disclosure: Nobody from any of the car magazines had been invited to compete, just local media types like me. (I was working for a daily newspaper at the time.) Also, I was a Malibu Grand Prix ringer with dozens, if not hundreds, of laps on this particular track. So it wasn’t a huge surprise when I posted the best time of the day and was sprayed with victory champagne.

But, hey, a win is a win is a win. And every time I saw Shelby after that, he told me, in his East Texas drawl, “Preston, you shoulda been a race car driver.”

Thanks for the memories, Malibu Grand Prix.

Is there anywhere I can buy one of these??

I’ve got one available

I think that you missed the story John Bickford has about taking Jeff Gordon to a Malibu Grand Prix track back when Jeff was told “you are not old enough to drive one of these”

In the mid 80’s I worked at the Faribault (MN) Grand Prix Track. We had the DeLorean GP of America cars, and they were far superior to the Malibu cars – especially after we replaced the anemic 309cc rotary motors with Kawasaki 2 stroke snowmobile engines. The owner was once I voted to bring one to a Malibu track – I think in St. Paul.

He was not invited back.

If I could find one, I’d make a killer autocross ride out of it!

300cc – oops!

I spent a good many hours in these awesome f1’s on the Oklahoma City track in the 80’s.

You would have known my dad! Bill Bloyed

I just came across this article. I was a mechanic at the Fountain Valley, CA track. I’d love to have me a Virage, then I’d rebuild it! For a couple of years we got to race them on the Long Beach Grand Prix circuit as a promotion before the real race. If you turned a few of us mechanics loose we could make those cars a lot faster than they had any right to be…