Stock Stories: 1949 Matchless G9 and AJS Model 20

By the 1940s and ’50s, parallel twin motors were by no means new technology. In fact, the first motorcycle to run this configuration was a Hildebrand & Wolfmuller motorcycle way back in 1894; it was driven by steam and is regarded as the world’s first series production motorcycle.

Here is how the parallel carved out a niche: By dividing the overall capacity equally between two cylinders, engine performance improved. The smaller flywheels saved weight while also offering a more compact design, providing smoother power delivery with less vibration and greater horsepower compared to a conventional single-cylinder setups, which gave a bigger thump and more vibration due to the longer stroke and bigger capacity of the cylinder. On top of that, twins are easier to start due to the compression stroke being halved in relation to the overall capacity; that means no need for old-fashioned decompression levers.

With the parallel configuration presenting a significantly more user-friendly experience, it’s obvious to see why Triumph decided to develop its own parallel twin in the Speed Twin, first released in 1937. Other British marques followed suit. When AMC (Associated Motor Cycles) released two parallel-powered bikes in 1948, the Matchless G9 and the AJS Model 20, it was relatively late to the game. These two bikes nevertheless left their mark both in Europe and North America.

AMC was founded in 1938 as a parent company to Matchless and AJS. It entered the game with the benefit of Matchless’ experience in multi-cylinder bike engineering. Matchless had made an almost inline twin with the Silver Arrow in 1930, using a narrow-angle 400-cc V-twin engine. That project led to the 1931 Silver Hawk’s doubled-up V4 arrangement, complete with a 593-cc capacity.

Despite these advancements, as AMC headed into World War II it concentrated on motorcycles with a more practical, more serviceable single-cylinder engine. This decision enabled the company to continue manufacturing during a period of extraordinary uncertainty and difficulty, when many other outfits gave over their production lines to munitions and other wartime items. Despite this, AMC still afforded its race department time develop a forward-inclined twin planned to be ready for when racing commenced after the war. This project was a development of a previous V4 racer that was deemed too heavy—hence the decision to go with a lighter twin.

AMC was well aware of the success BMW experienced with its supercharged flat twin, which won the 1939 500-cc TT, and the idea was to introduce a direct competitor. Initially designed to be supercharged, this over-engineered unit had very long spine-like cooling fins that inspired its nickname: the AJS Porcupine. The frame and cycle parts of the Porcupine were drawn up by Phil Walker, who went on to design the vertical twin engine for AMC.

Phil Walker moved along with AJS, where he was Chief Designer, when the marque was bought up by Matchless in 1931. Walker designed the vertical twin 500-cc engine for AMC, which was playing catchup with Triumph, BSA, and Ariel which already had their own twins, while Norton and Royal Enfield were looking to release theirs in 1948 as well. With all this competition, Walker had to design an engine that would offer more than just the established advantages of the parallel twin.

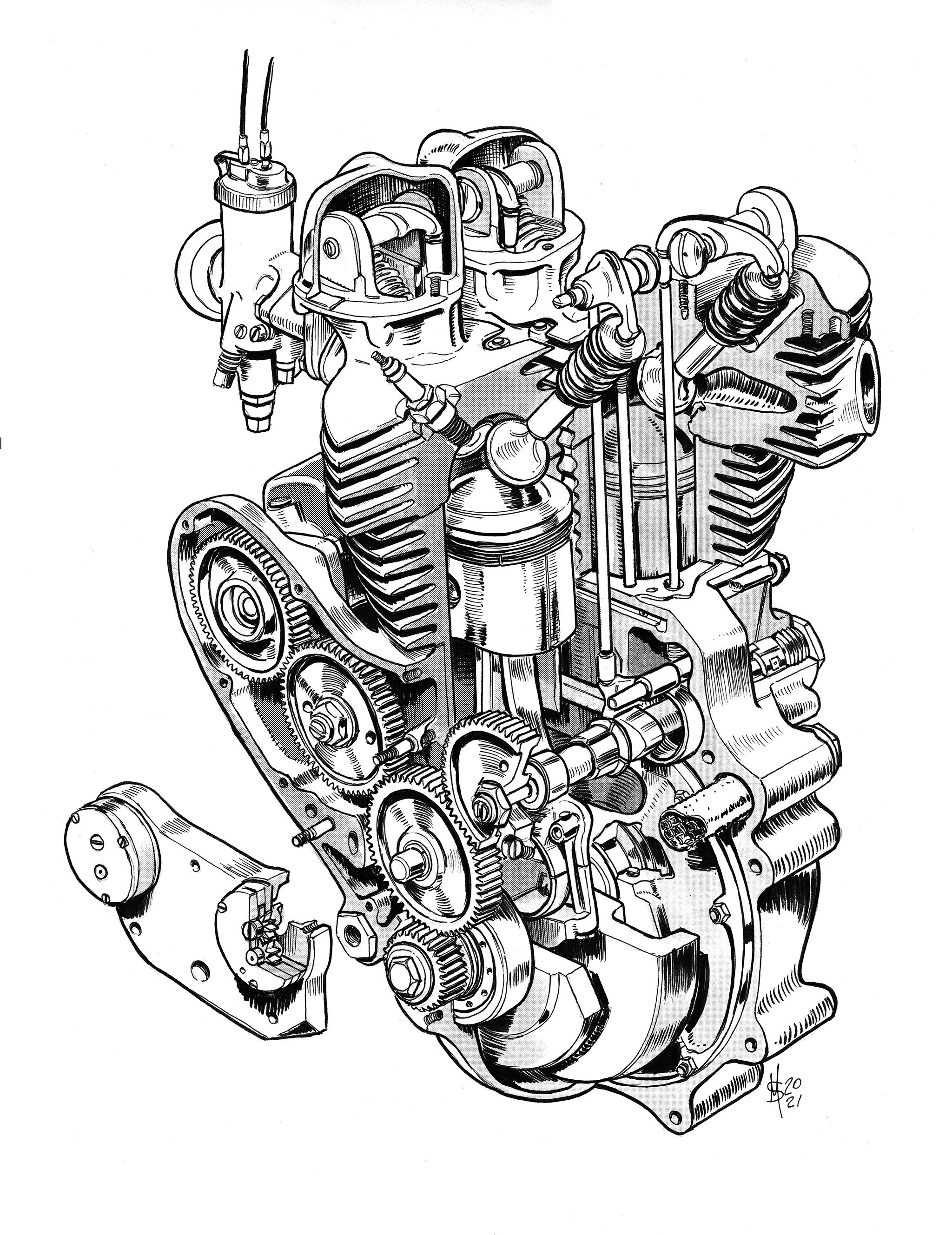

Knowing his AMC history, Walker explored a major development that was particular to AMC engines: an additional support between the connecting rods to reduce crankshaft flex. This was done via a two-piece shell bearing fitted to a large circular aluminum plate bolted around the center of the crankshaft. Recessed into both sides of the crankcase, this clever support substantially reinforced a crankshaft that had two flywheels. AMC used implementation in the V4 engine and again in the Porcupine, and Walker took advantage of this arrangement to incorporate an oiling system that delivered oil to the centre of the crankshaft—a fantastic design that lubricated the crankshaft evenly while all the other marques lubricated their twins from one end of the crankshaft, often leaving the opposite end insufficiently lubricated.

Another element of AMC engine construction that rose from the development of the Porcupine was the highly polished connecting rods constructed from an alloy called Hiduminium R.R.56. The top end of the engine utilized two separate barrel castings this provided both a gap between them to aid cooling and also enabled one cylinder to be serviced without touching the other. The aluminum heads were detachable, made with fins that allowed cooling across and between the rocker boxes, and were fed with a single Amal carburetor.

Outside of the engine, both the Matchless G9 ‘”Super Clubman” and the AJS Model 20 “Spring Twin” debuted at Earls Court show in October 1948. Both sported full telescopic suspension on both the front forks and the rear swinging arm, with the early versions including what are referred to as “candlestick” units (long and slender) on the rear. At the time, having full swing-arm suspension was a cut above the competition. All the other marques sported inferior plunger suspension units.

Advertised as capable touring machines with the full suspension setup and long double seat, the twins were clearly aimed at the American market first and foremost. American riders had a thirst for British machines, especially the larger-capacity ones. Ex-service men, too, had the spare money upon returning home to spend on luxuries such as a new motorcycle. Though the machines were revealed at a British show, the first batches were for export only from 1949—1950 with the majority going to America and a few making their way to Australia and New Zealand.

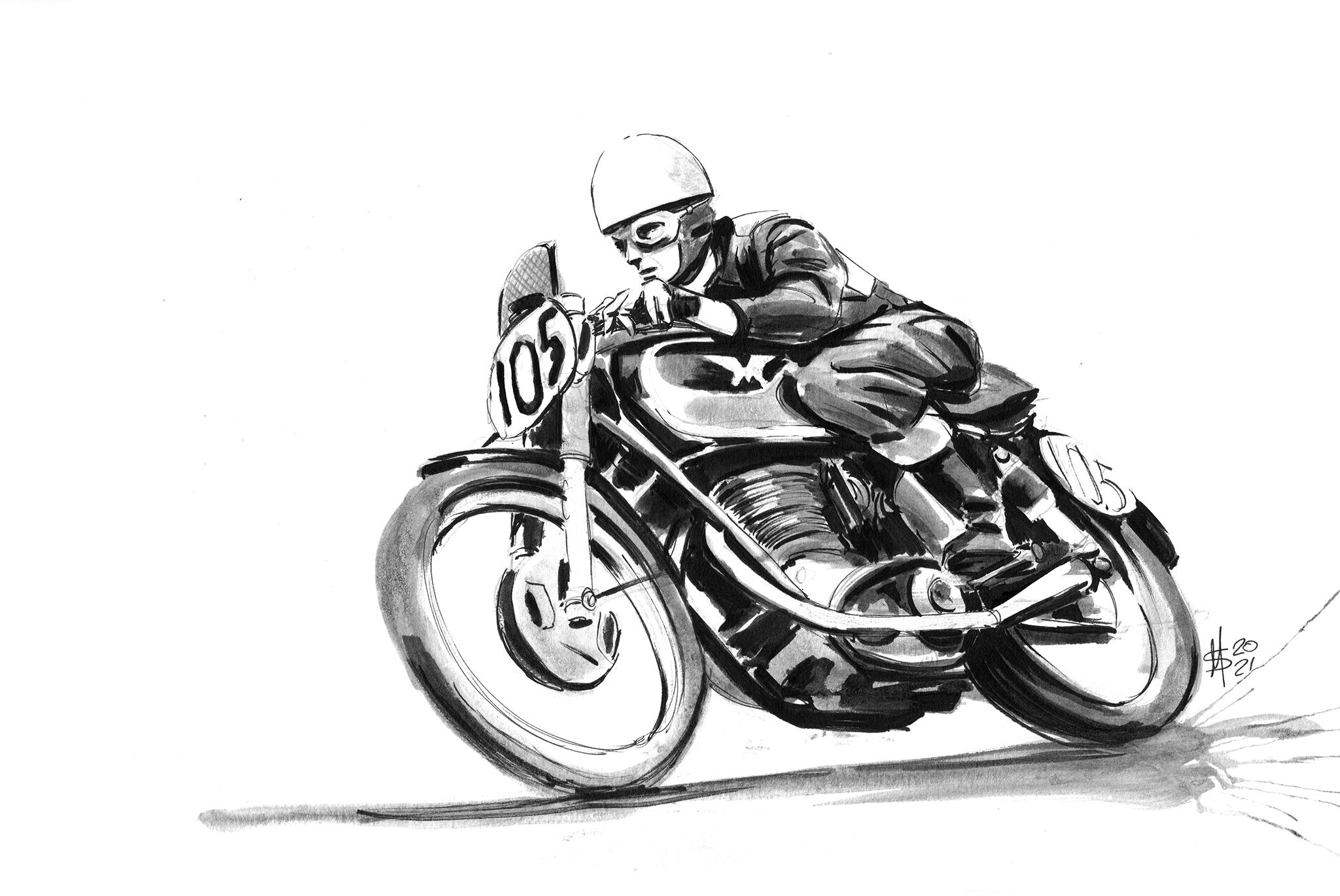

British customers finally got their hands on the twins from AJS and Matchless in 1951. By this time both models wore the more substantial “jam pot” suspension units on the rear. In the same year, the race department at AMC had put a Matchless G9 engine into a 7R frame, entering the bike intointo the 1951 Manx Grand Prix on the Isle of Man, under the Matchless name. It was an effort to promote and boost sales of the G9 and Model 20, but minimal development time was available due to more man hours at the time being dedicated to the Porcupine. This prototype racer, and its rider Robin Sherry, achieved fourth in the Grand Prix that year—enough for AMC to dedicate more time to the project. The following year, in 1952, the G9 returned to the famous TT race, where it set new records in the Senior Manx Grand Prix and won thanks the capable hands of rider Derek Farrant.

With this victory AMC started to more seriously examine taking the racer into production, with H. J. Hatch directing the project. The product was the Matchless G45, shown at Earls Court in November 1952, where AMC announced that it would produce a limited run for the 1953 season. It is believed that around 80 G45 racers were made over the next few years. The success of this G9-engined race bike gave the AJS and Matchless road-going twins a critical pedigree. From there, AMC pursued further efforts to secure competition wins and provide road-going customers with sportier options for their twins—a strategy that played out well for the brand in the competitive American market. The G45 would retain the 66 x 72.8-mm barrel dimensions of the G9, as well as the main bearings and the Hiduminium R.R.56 connecting rods, which unfortunately proved the main cause of engine failure. The main hot upgrades to the stock engine were deeply finned alloy cylinder heads that were fed by twin Amal GP carburetors, while the bottom end benefitted from an alloy steel crank shaft with shrunk-on flywheels.

In 1953, the first production G45 racers competed in the opening race of the 1953 season at Silverstone and 12 competed in the Senior TT that year. Unfortunately, nine of them retired. It was George Scott who would bring the works G45 back to success when he set the fastest 500-cc time at Nürburgring in a non-championship race. Another race at Tubbergen, in Holland, Scott was in second on the final lap of the race and crashed badly while trying to overtake Keith Campbell. The works G45 was scrapped due to the crash. Going into the mid-1950s, the G45 managed two wins in the New Zealand Grand Prix (1954– 1955) and fifth in the 1955 Dutch TT.

There were some revisions for the 1956 version of the G45 in the valvetrain and head castings, but AMC shifted its attention back to a single-cylinder racer using the 7R, which became the G50, realized in 1959. Such is the way of the racing machine; the G45 had served its purpose and proved that AMC’s G9 engine was a true performer. With racing success under its belt, AMC offered customers an optional racing kit in 1953 which included high-lift cams, twin carburetors, high-compression pistons, megaphone silencers, and an optional rev counter.

AMC continued to produce the G9 up until 1961, and the Model 20 was replaced in 1958 by the Model 31. These bikes were the first in a series of vertical twins that AMC would produce, including the G12 and Model 31, until the company went bankrupt in 1966. These vertical twins were not flashes in the pan; they had a reputation of being reliable, well-made, and possessing good handling. Though they never sold in the volume that twins from BSA and Norton did, the G9 and Model 20 were evidence of the British companies’ widespread adoption of the technology that defined the 1940s and ’50s.