3 essential alignment terms, explained

Handling is a word you will read frequently in the automotive world. Journalists, race car drivers, and manufacturer reps will debate the handling nuances between different models to no end, referring to subframe bushings and spring rates and how exactly the actuation of power steering may effect a car’s behavior. Despite the infinite array of technical terms, most of the time a car’s handling character is determined by three steering adjustments.

Here is a brief explainer of the three key alignment terms when discussing an automotive steering system.

Toe

This is the easiest characteristic to spot with the naked eye. To calculate toe more precisely, measure the distance between the centers of the two steering tires on both the leading edges and trailing edges. If the distance between the leading edges is narrower than that between the trailing edges, your vehicle is set up with “toe-in.” The opposite is “toe-out.”

The toe setup on a car significant impacts its turn-in performance. Excess toe-in can make a car feel very “darty.” Too much toe-out will make a car respond lazily to steering input. Both conditions accelerate tire wear. Like most good things in life, the key is balance. Rear-wheel-drive chassis are often best served by a slight toe-in setup. As a car’s body rolls into a corner, the suspension effectively moves the wheel backwards, bringing the toe to neutral. Front-wheel-drive vehicles typically respond well to mild toe-out: During straight-line acceleration, the force transferred through the tire pulls it forward slightly, thus neutralizing the toe adjustment.

Caster

Picture the front wheels that spin on your shopping cart when, as a purely random example, you’re picking up your favorite discount oil when you told the missus you were making a toilet paper run. The contact patch of the shopping cart’s wheel falls significantly behind the steering axis (also shown in the caster wheel below). This rearward placement makes the wheel trail along steadily, but only because it isn’t steering—it is being steered.

Caster on a vintage car (like my Model A, on the left) is typically non-adjustable because it is synonymous with the kingpin angle. Without changing the axle there is no way to change the angle of the kingpin. Modern cars, on the other hand, often allow you to make changes in caster. A positive caster angle will makes the wheels straighten out quickly following a turn. Negative caster will make the car feel unstable when you attempt to drive in a straight line.

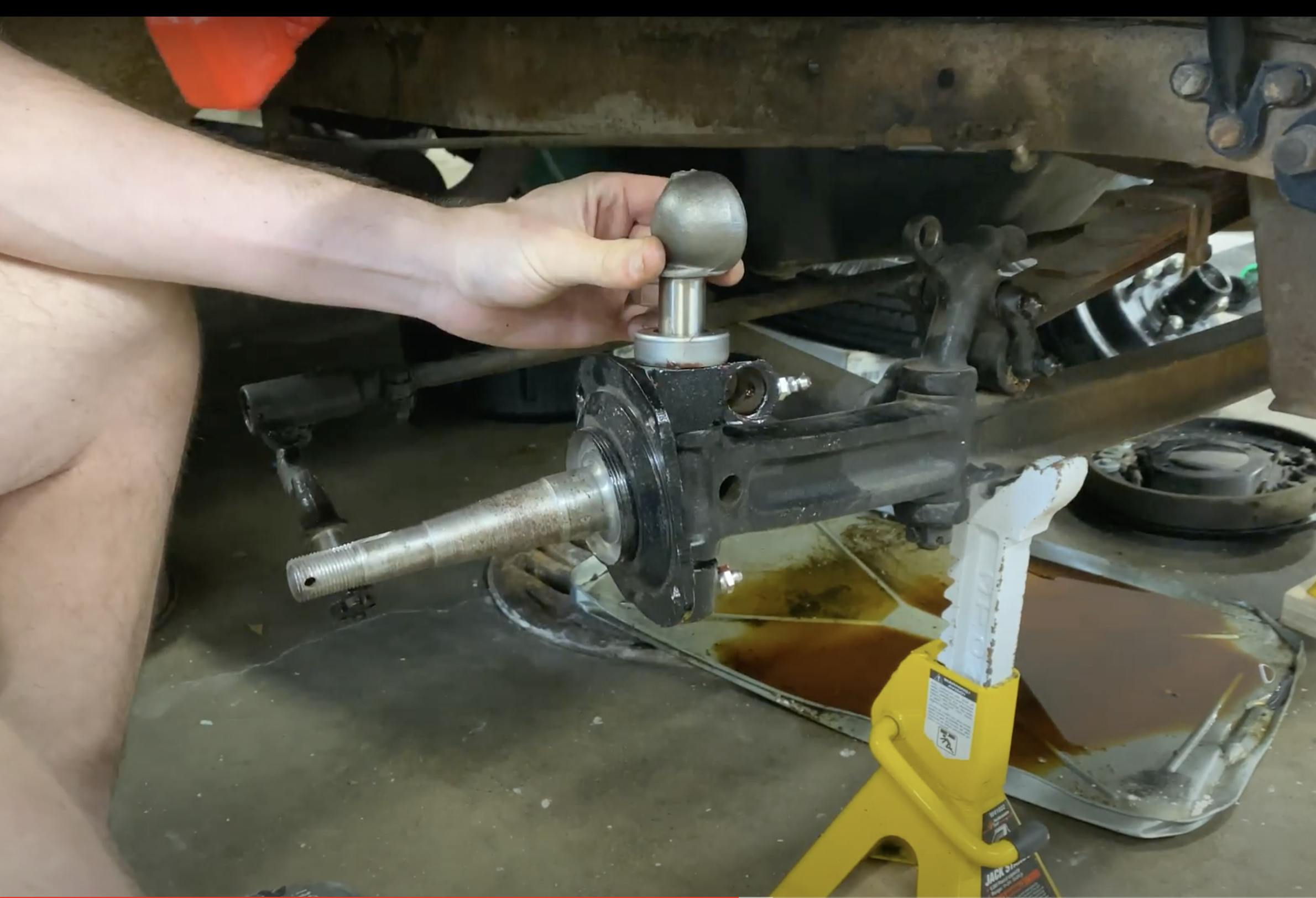

Camber

This is the angle of the wheel and tire relative to vertical. If the tire is angled with the bottom edge sticking away from the vehicle, it’s displaying negative camber; the top of the tire leaning out would show positive camber. Each angle has its merits, but in general, deviating from your car’s original camber specification comes with some sort of trade-off in handling.

Because camber helps determine steering effort, a slight adjustment to it can disproportionately change the character of a car. Most street-driven cars have slightly positive camber, which combines with the suspension design to minimize steering effort and tire wear. Race cars, which tolerate heavier steering input, may use zero or even mildly negative camber because those angles keep more of the tire in contact with the road during a corner.

Is there a term or system from the automotive world that you just don’t understand? Let me know what it is in the Hagerty Community, and I will dig into it and see if I can’t help you get a better grasp on the technical side of this great hobby.

Beam axles can be adjusted for caster by inserting a wedge shaped shim between spring and axle. Camber adj. are also made by heating and bending the axle. Pretty common in frt. end shops.