Goodwood on silver halide: Why I’m now a film-camera convert

Click.

I bring the camera down from my face and, for the umpteenth time today, take a look at the back, expecting to see … well, something. Anything.

Muscle memory is a powerful habit, as it turns out. Years of using digital cameras has conditioned us into immediately glancing at the back of our devices after taking a shot, and quickly deciding whether the image stays or goes.

You do not get that option with film.

I wasn’t the only person swinging around a traditional camera at this year’s Goodwood Revival, but as a way of capturing the event without breaking the vintage illusion by whipping out an iPhone, my recently-bought Olympus 35RC would do nicely.

Truth be told, the 35RC is a little new for Goodwood’s 1930s to 1960s time capsule—it arrived in the 1970s—but the decade’s smallest 35mm rangefinder seemed to do the trick as a prop at the very least.

Looking the part was important, as it might be all the camera offered me. Before this September, and Goodwood, the camera was completely untested. Other than throwing in a roll of Fuji 400 ISO film and a battery to help it choose exposure, I had no idea whether every frame I captured would be an overexposed, light-leaky mess.

Nor did I know if the lenses were out of focus, or whether the shutter button was even operating correctly. Essentially, it was the photographic equivalent of buying a car sight unseen a few days before the Revival and hoping it’d get you there and back without so much as an oil change.

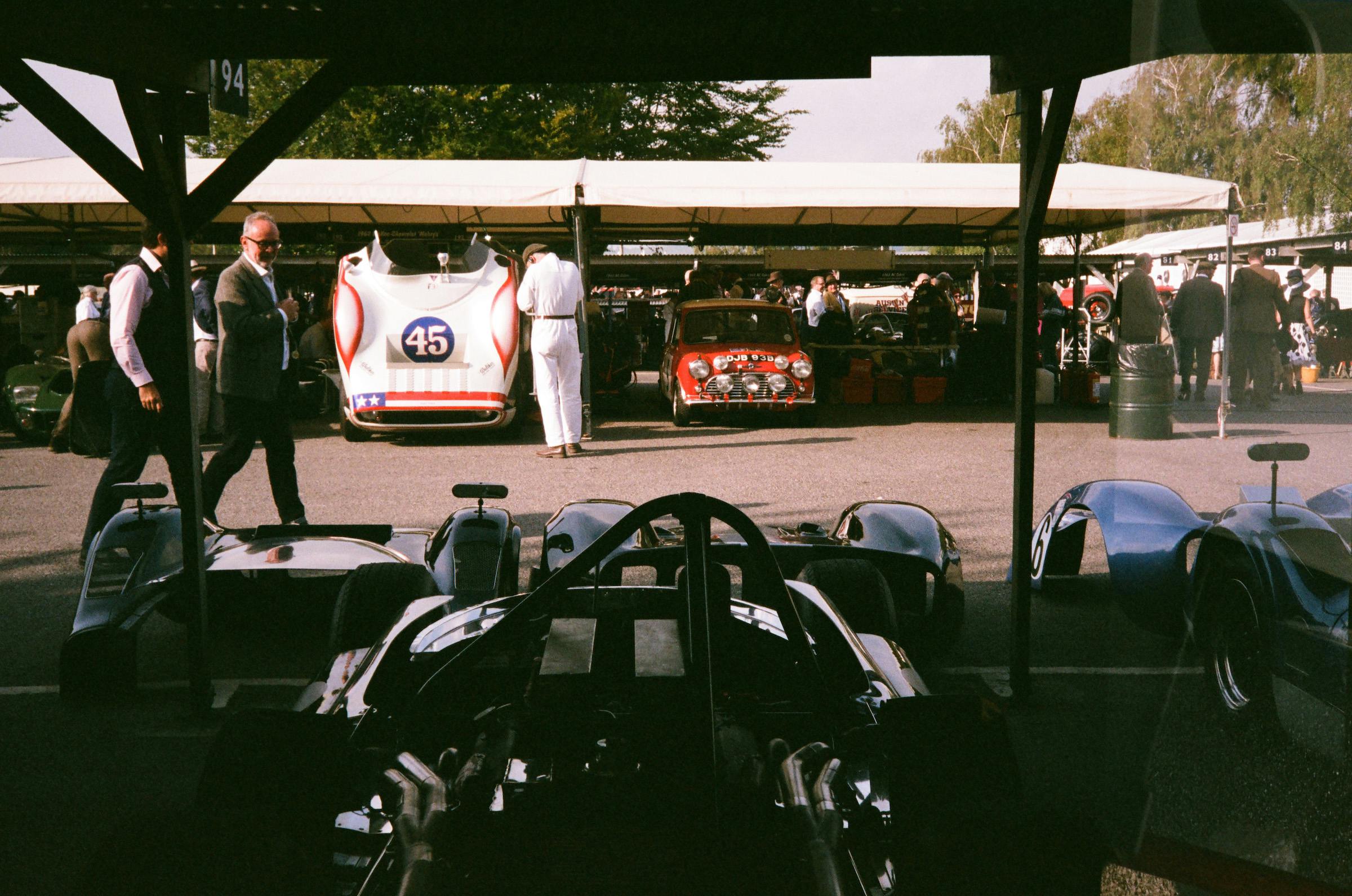

Clearly I had little to worry about, as you can see on this page. My technique needs some refinement (partly because I don’t practice enough, and partly to adapt to the unique demands of shooting on film) but for the most part the camera itself seems to be absolutely spot-on. Considering it cost all of around £50 (~$68) posted, I’m taking it as a small victory.

I had a roll of 36 frames to work with. I wasted some making absolutely sure the film was correctly loaded (it was). A further dozen simply weren’t very good shots (so I’m not reproducing them here). Those you see here are what remained. A handful I’m genuinely pleased with (the snap of a Mr. Rowan Atkinson among them), but all somehow feel appropriate to the event at which I took them, offering a feel you still can’t quite achieve by just slapping on an Instagram filter.

Better than the photos, though, is the satisfaction of returning to film for the first time since my teenage years. It might have escaped your notice that—a little like vinyl records, organic food and, indeed, classic cars—film photography is today enjoying a resurgence.

People are increasingly ditching the instant gratification of digital for the warmth of film stock, excitement and mystery of development, and the challenge of making each shot really matter—since you can’t simply take a burst of frames and delete all but the very best.

So, a suggestion. If you’re planning a trip in your classic car, or a visit to an event, why not pick up a film camera rather than absentmindedly snapping away at everything with your phone? Pop “vintage camera” into eBay and see what comes up; before the Olympus, which took some attempts to get for a decent price in an auction, I’d spent just £6 (~$8)on an old East German camera which itself takes perfectly decent shots.

You won’t take as many photos as you might on an iPhone or modern DSLR. And the ones you do get might just be terrible. But like opting to drive a classic instead of a modern car, the rewards for making the effort are so much greater.