Without Toby Halicki, 2000’s “Gone in 60 Seconds” was always doomed to disappoint

Movie remakes are, to put it mildly, a controversial enterprise. While there’s always a sense of duty to repackage old tales into contemporary packages, we’ve all noticed a unique phenomenon in film where a relatively fresh story will be “remade” just a few decades after the original picture. The problem with this approach and unlike, say, Disney reformatting centuries-old story books into motion pictures, is that it creates a certain expectation of what the final result should look like.

The 2000 version Gone in 60 Seconds drew ire from die-hard fans of the original film, which was something of a cinematic marvel when it was released in 1974. If you ask the generation who grew up around Henry Blight “Toby” Halicki’s mechanical bar fight and the era of carnage that followed, their whole argument could typically be summed up in a few words: “The chase wasn’t as good. “But to truly understand why 2000’s Gone in 60 Seconds failed to live up to the original, you have to understand just what Halicki accomplished and just how insane his life truly was—just before it was cut short in his own attempt at a Gone in 60 Seconds sequel.

In many ways, he set the stage for the conditions that led up to the immeasurable expectations of the 2000 remake. And for once, you can’t blame Nic Cage.

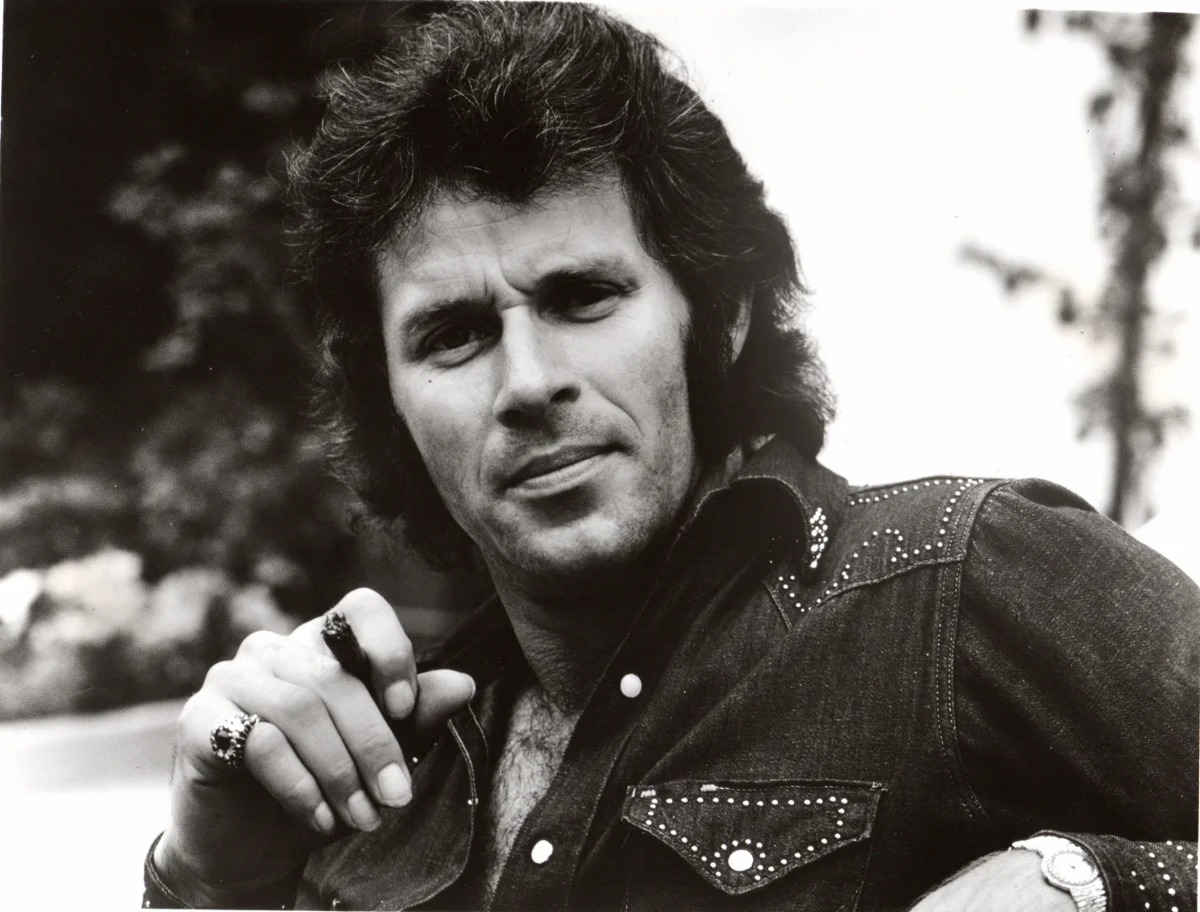

The Man, the myth, the junkman

Born in a family of 12 siblings in Dunkirk, New York, the self-described “Car Crash King” was raised in his own sort of chaos. At the age of 15 he landed in Gardena, California, with the help of his uncle, though the legend goes that his westward rush was spurred after his mother attempted to ban him from earning a driver’s license in New York. Starting as a gas station attendant with just $40 in his pocket, he eventually followed in his father’s footsteps with his own workshop and tow yard. He began to thrive in Southern California’s mix of Hollywood and hotrods, while amassing his own collection of unique cars. The scrappy junkyarder would begin to build the life which his art imitated when he was indicted in 1968 with auto theft charges related to a rash of crimes at the LAX and SFO airports. The cars were stolen before their VIN plates, lock cylinders, and serial-numbered parts (like the driveline and VIN-etched glass) were swapped with the salvaged replacements from a junked (but otherwise clean-history) donor car. With an official “rebuilt” title in hand, the stolen cars were allegedly sold in Inglewood to unsuspecting buyers gleaming at a killer deal on their new wheels. While the charges against Halicki were eventually dropped, the inside world of professional car theft rings—that is, separate from the impromptu crimes of opportunity that most people imagine—inspired the storyline for Gone in 60 Seconds.

Over the next few years, Halicki began to realize that the key to his future success was in Hollywood, which was still in its golden-age of filmmaking. He had the vehicular supply chain, the right friends in just low-enough places, and just enough cash in his pocket for a stack of film reels. But without inside ties to the big studios hiding just 20 miles north, and almost shunned, the shoestring showman had to make other plans. If Roger Moore could prance around in a suit and an Aston Martin, then why not Halicki in, oh say, “the last of the Mustangs?”

The 1973 Mustang and the end of an era

“Hey Stosh, look it, at 3 o’clock… Another Eleanor.”

“Whenever you don’t need them, they’re all over.”

“She’s sure been a lot of trouble. Probably because she’s the last of the Mustangs.”

For Americans, the coke-bottle monsters rolling out of Detroit were sacrificed in 1973; the legacy of muscle car performance will always be staked by the malaise era’s crushing regulatory and economic crisis. The Clean Air Act moved aggressively on vehicle emissions while OEMs reeled away from fire-breathing V-8s. 1973 was to be the last year of what many saw as the true Ford Mustang: the fastback Mach 1. Debuting without a V-8, Ford’s upcoming Mustang II was already seen as a sharp diversion, and when Maindrian Pace (Halicki) and Stanely “Stosh” Chase (James McIntyre) put their eyes on what would become the one true Eleanor in the film’s chase, the pedestal that they placed her on could’ve have been more justified.

With their leading lady in mind, Halicki went on a buying spree at local auctions for some 200-plus vehicles. If he was to make the world’s greatest car chase, he was going to need a fleet of police cars, garbage trucks, fire engines, sports cars, and generic sedans to ping-pong Eleanor off of during the pursuit.

“Action first, dialogue later”

Them Duke Boys hadn’t even gotten their licenses yet, though the bar had been set by big-budget entries like Bullitt and The French Connection. In fact, Gone in 60 Seconds would debut nearly six months before The Man with the Golden Gun’s ground-breaking corkscrew jump. The template for the world’s greatest car chase was being drawn in Halicki’s mind as he wrote, directed, and coordinated the litany of stunts seen in the film. Being a creature of opportunity, one of the more iconic scenes established just how scrappy Halicki could be in his infamous action-first-dialogue-later approach to production. Put yourself in his wing-tipped shoes: you’re an indie filmmaker pulling shoestrings when you hear that a train has derailed at a nearby railyard. Great!

He didn’t have the budget to stage a train crash; instead, he slammed his film crew into a station wagon and hauled down to the scene of the accident. With enough pleading and charm, he convinced the officials to let him film the opening scene of Gone in 60 Seconds while the actual investigation and clean-up crews worked in the background. Whether it was his smooth talking or a palming of a few greenbacks, Halicki’s guerilla filming tactics had only just begun.

The gonzo filmmaker routinely used public locations instead of hiring extras. The scenes shot inside Ascot Park were filmed during a typical race night while the crowd knew nothing about Halicki’s cameras. Many of the action scenes on the road were shot on Sundays alongside unsuspecting motorists making their way around the areas of San Pedro, Carson, Wilmington, Harbor City, Torrance, Terminal Island, Long Beach, and Redondo Beach. Why Sundays? Halicki learned that the lone officer in charge of enforcing filming permits for L.A. County didn’t work Sundays. If he could keep tidy, he thought, he could easily film a bulk of the chase with the public as unwitting extras. In some scenes, you can even see people on the sidewalk reacting to what they think is a real police chase or car crash.

Try that with not just today’s traffic in the Harbor region of Los Angeles, but also the dragnet of police cruisers, motorcycles, and cameras that comb So Cal’s streets and highways for miscreants such as him. But for the most part, he was right. Several scenes filmed along the Harbor Freeway corridor were simply Halicki and his camera crew tearing through traffic with cameras hanging off the tailgate of a station wagon, terrorizing otherwise benign on-ramps and intersections. Sure, he pulled a few favors with local officials to close streets in some scenes—notably the mayor of Carson City, Sak Yamamoto, who played himself in the film—but skirting the costs and bureaucracy of permitting with nearly a dozen city halls proved to be his greatest asset, next to his sheer driving talent, in getting Gone in 60 Seconds’ ground-breaking chases in the can.

But while most of the major crashes you see were almost begrudgingly done with the nod of local officials, most were written into the script rather “organically.”

Twisted metal and the human toll

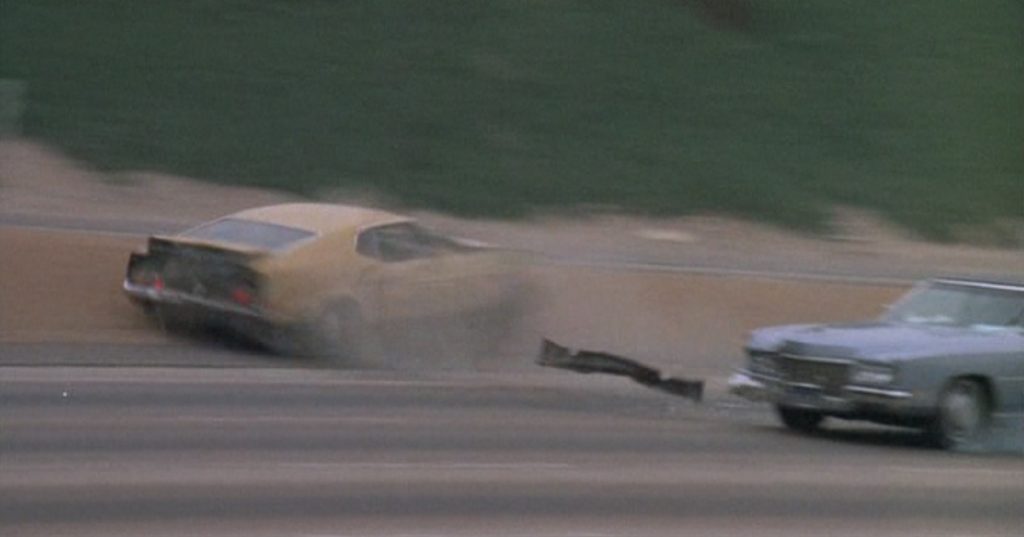

The chase began at the International Towers in Long Beach, with two police investigators in a four-door Gran Torino doing their level best to finally catch the ringleader. The smoking gun? Pace forgets to disable Eleanor’s car alarm before leaving the garage, giving investigative unit 1-Baker-11 all they needed to begin pursuit along Ocean Ave. Before too long, Pace and Eleanor are terrorizing pedestrians through Lincoln Park and the surrounding streets. With Terminal Island on the horizon, Pace shoots for the Gerald Desmond and Vincent Thomas bridges before under-cutting (presumably unaware) traffic on the inside shoulder, sling-shotting north on the Harbor Freeway as L.A.’s finest lose control behind him on the banked interchange. Slicing lanes to make the Sepulveda exit, which now is home to the likes of Target and LADWP’s sewage plant instead of the endless fields seen here, Pace begins to throw his pursuers through a maze of underpasses, bridges, and dirt roads as he winds past the refineries of Carson. With a handful of cunning maneuvers near the old Ascot Speedway—leaving several units dropping into ditches and high-centering on hills, including our intrepid 1-Baker-11—the chase grounds itself back on the pavement with nearly every black-and-white known to SoCal left in the dust as Pace and Eleanor scream back onto today’s 110 North.

Unfortunately, Halicki’s luck finally ran out. In a daring move to cut across four lanes of traffic, near the 220th Street exit, one of his fellow stunt drivers put the nose of their Cadillac into the rear bumper of Eleanor during the overtake, P.I.T. maneuvering the nearly-100-mph Mustang into a light pole.

This wasn’t planned—even with Halicki’s reckless abandon and his custom NASCAR-caged Mach 1, the hit was absolutely not the result they wanted from the shot. Eleanor rotated 90 degrees before striking the pole with the front-driver’s fender, narrowly missing the passenger compartment that held Halicki, though some reports mention that Halicki broke his leg and drove the rest of the shoots in a leg cast. The yellow Mustang was instantly banana’d and came to a rest as the light pole smashed into the unclosed lanes of the Harbor Freeway.

“Jesus Christ! He just hit a damn post!” yelled the co-pilot of Unit 1-Baker-11, but you can imagine the production team shouted much worse upon seeing the split-second mistake turn ugly. In the movie, Pace and Eleanor brush off the hit and dive into the streets of Carson City along Figueroa; the reality is Halicki was found unconscious before yelling that this was the take to keep and to get the show back on the road. Apparently they returned later to film him extracting Eleanor from the median after some repairs, leaving the pole for some poor Cal-Trans worker to find.

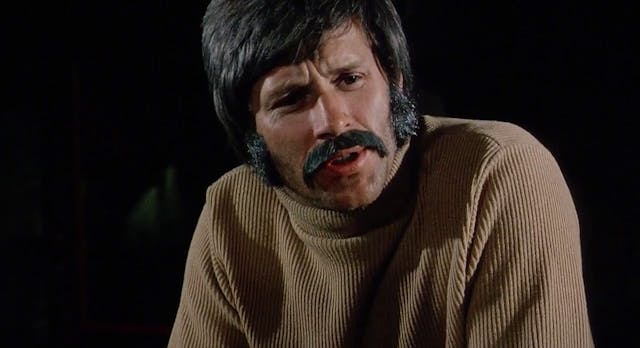

Not long after that scene is another narrow miss for the Gone in 60 Seconds stunt team. The police begin to set up a roadblock at a dealership and the plan was to whip Eleanor around with a handbrake-180 ahead of the roadblock, with inches to spare, before whipping back around against her pursuers. Actor J.C. Agajanian stood by the blue Plymouth Belvedere that was creamed, staring down the eyes of Eleanor as Halicki came in hot—hotter than anyone was expecting.

“I can see Toby just haulin’. I mean, he’s hauling down the street!” Agajanian told Speed TV with a chuckle. “And I’m going, ‘He’s gonna do that trick turn-around thing any second now!'” Thankfully, our man Agajanian didn’t wait for Halicki to make his planned move, as he jumped behind his unmarked cop car and ran back a few steps just as Eleanor plowed into the quarter of the unsuspecting Belvedere. In all likelihood, if Agajanian hadn’t been on full alert, Halicki would’ve had a lot of questions to answer for on the other side of that scene.

Like Chow from The Hangover, Halicki’s persistence in the face of danger leads us to the film’s defining moment. Along 190th Street’s famous hill near Redondo Beach, just before reaching the coast, was to be his crowning achievement. Cresting Flagler Lane with the throttle welded to the floor, a ramp was set up at the bottom of the 90-foot slope to launch Eleanor. Everything had come to this moment for Halicki. Over $100K of his own money, grown from that fistful of dollars in Gardena. The 90-plus demolished machines slaughtered like lambs. The close-calls and broken barriers. The madman behind the wheel knew one thing mattered, that it looked as brutal and real as possible.

And brutal it was, both to the decrepit Eleanor and Halicki’s vertebrae as he crushed somewhere around a dozen of them as the Mach 1 landed back on 190th Street with the grace of a drop-kicked elephant. He used the downhill portion of 190th like a ski jump, ramping the car over a pile-up of wrecked cars before plowing nose-first into the pavement after soaring a 128-foot gap at an altitude of 30 feet. It’s said that Halicki would never walk the same again, but our main character, Pace, brushes the crash off and spots another yellow Mach 1 as it reveals itself from a car wash. Pace bait-and-switches the car at the last second while the coppers are still tangled in the wreckage he had miraculously leaped over.

Both life and death imitated his art

While Hollywood and the major theaters refused to take him seriously, Halicki went on a nation-wide spree with the wreckage of Eleanor, knocking on the door of any independent theater he could in every major market between the Pacific and Atlantic to sell the flick. Allegedly, he even hired a strong man named Big Tiny to shakedown the few theater owners who refused to pay Halicki his box office sales, but by the end of 1974, if you were a fiend behind four wheels, you knew about the 45-minute thrash that defined Gone in 60 Seconds’ rascally plot. Halicki spun the success of Gone in 60 Seconds, which grossed $40 million dollars (over $200 million in 2020 bucks) into a dense series of flicks that continuously upped the ante, and danger. Until it all came crashing down.

The Junkman was released in 1986, and Halicki’s career kept elevating the high watermark for stuntwork. Without writing another thesis (maybe for another day), The Junkman is best described as a caricature of Halicki’s life; a rising junkyard owner/local hero is targeted by a crew of hitmen as he tries in vain to attend the James Dean Memorial Show. Leveraging his newfound fame, the flick is a true celebration of ’70s-80s stunt work and car culture, this time escalating the vehicle violence to more than 150 cars and a handful of planes destroyed in what would become a Guinness World Record. He followed that up with a supercut of Gone in 60 Seconds and Junkman, called Deadline Auto Theft, that gave Gone a more cohesive plot thanks to the addition of clips from Junkman.

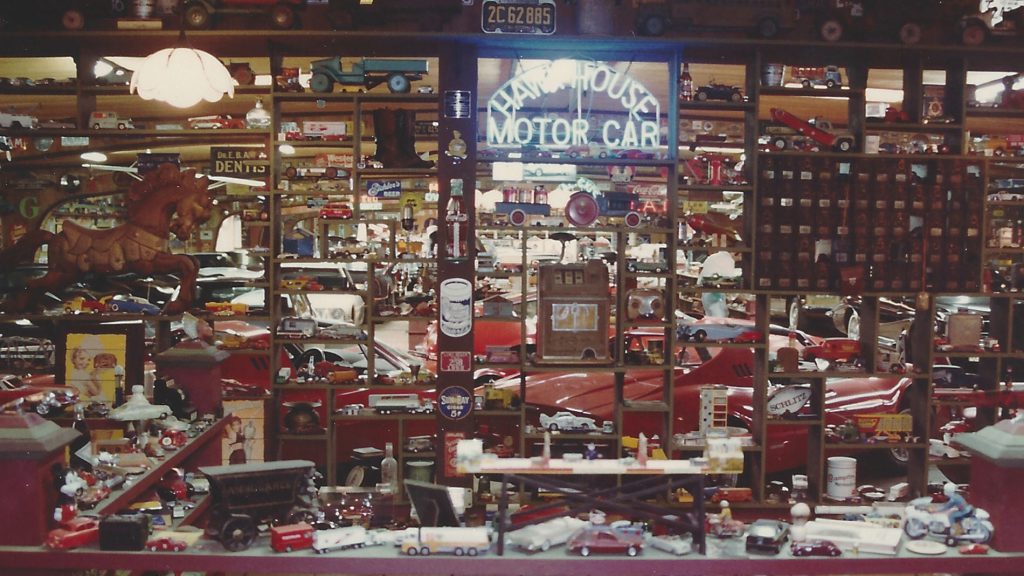

Halicki had also begun to amass a sizable collection of toys, cars, and memorabilia at his Gardena-based “H.B. Halicki Mercantile Co. & Junk Yard” compound. The interior was broken down into different sections, but carried a western saloon aesthetic wherever possible, including period-correct doors found in the deserts around California. Even with the nostalgic facade, the collector’s compound still had some trick tech: notably, an office wall near his desk that allowed him to park just a few feet from his throne.

Things were looking good for Halicki as he entered production of Gone in 60 Seconds II shortly after honeymooning with his new wife, Denice. He pulled favors from every direction, including his own family in New York state. Upping the ante over the original film meant that he had to buy and build an ever larger fleet of vehicles, including Gone in 60 Second II’s unique “Slicer,” which was built by Halicki’s family in Dunkirk and looked like a life-sized battle bot. It’s sole purpose was to sling cop cars around thanks to the wedge-shaped body, and the footage they capture is straight out of fantasy. All told, there were allegedly 400 vehicles slated to be used in the film. The footage that’s in the released version is bonkers; you’ll never look at an 18-wheeler the same after the brutality Halicki inflicts with a cab-over International. Approximately 240 of those vehicles were damaged in the filming that led up to Halicki’s death in 1989.

The film’s penultimate stunt, where the IH big-rig was to slam into a 160-foot water tower, is when the story takes a dark turn. The stunt was complicated and came after a long battle with Tonawanda’s town officials for the approval of a destruction permit. Perhaps having seen his previous films, officials demanded that the production company of his brother, Ronald Halicki and Project Films Inc., pick up an $8 million insurance policy, sign a liability waiver with the town, and pay a $10,000 cash bond. The tensions even escalated to one bizarre gift from Halicki to Town of Tonawanda Supervisor Ronald H. Moline, according to the Buffalo News: “Halicki presented the supervisor with a pair of trousers with a propeller attached to the seat, because Moline had at one time referred to Halicki’s production as a ‘flying-by-the-seat-of-his-pants’ project.’”

At approximately 5:50 pm, on August 20, 1989, the crew was cutting the last of the supports needed to stage the tower’s fall when it began to collapse. It was common practice in demolition to preemptively weaken the structure so that its fall can be directed to some degree, but the 160-foot water tower came crashing down before anyone knew how to react. In the final cut of Gone in 60 Seconds II, the film retains a shot of the tower’s fall, but it’s in that moment that Halicki is killed on set. He had turned to run, but a support cable snapped, hitting a telephone pole, which fell onto him. Halicki was pronounced dead upon arriving at the hospital with severe internal injuries.

The end of an era

Maybe now when you see Nic Cage’s detached reaction in the reboot to the impact of a jump that just, frankly, never happened, you get the principal of the rub that the original fans bear. The 2000 remake was, on the basis of being a cohesive story, a substantial leap in plot and polish. But, at its core, Gone in 60 Seconds could’ve hinged its chase scene around any plot. If Halicki had lived long enough to somehow fall into a trap of producing The Bachelor, you could still expect the contestants to have to survive a 45-minute demolition derby to make it to the next episode. The panache and swagger of Halicki bled into his films, earning his stripes with each release that brought method to the madman. It was in many ways the reason films after it, including the 2000 remake, felt so neutered.

Looking back, 1989 was a fairly grim year for deaths in the filming industry, and the question of whether or not hyper-realistic stunts were needed to convey action when special effects, including CGI backdrops, explosions, and scenes were becoming as safe as they were cost-effective. Halicki even had to finally concede to this fact in The Junkman. He just couldn’t get a low-flying shot of an aircraft over his Eldorado without the stunt plane crashing into the Caddy, and only after suffering a number of stitches after the wing tip came through the windshield did he decide to rig the fuselage of the aircraft onto a truck for a final shot.

In many ways, the Bruckheimer remake could never be as raw as the Halicki original. Halicki’s films existed against all odds, in spite of Hollywood, not in its over-produced hands.

I would like to buy the “Slicer” vehicle from the movie if anyone knows it’s whereabouts.