20 mph in a 1906 Cadillac Model K Runabout is controlled mechanical violence

Cars of yesteryear are our passion. We dig fins, muscle cars, and vintage Corvettes without prejudice. But seldom arises the chance to set the Wayback Machine for 1906. Thanks to Rich Robell of Novi, Michigan, we have the privilege to share a few moments from the driver’s seat of an utterly amazing 1906 Cadillac Model K runabout. After more than 115 years, it’s still vibrates with the ambition of creators eager to brave the road to tomorrow.

Going into our drive, Robell was impressed neither by the thousands of road tests under my belt nor my 200-mph passes across the Bonneville Salt Flats. To merit a spin in his Cadillac, I had to first prove I could start its engine. How hard could that be, when this car’s original owner was his 5-foot-tall great-great aunt Beatrice? Turns out, cranking the old beast is tougher than the measly 10 pushups I manage at the gym every morning.

Step One: Click the ignition switch and prime the carburetor by tugging a rod until fuel drips onto the pavement.

Step Two: Insert the crank handle into a hole in the runabout’s left frame rail. Awkward as that location seems, Robell explained that Cadillac chose it for safety reasons. A common accident for early cars with front-located starting cranks was flattening the driver when the engine fired. A second thoughtful measure was to block the crank’s access hole until the spark advance lever had been set to its fully retarded position, where backfiring is less likely.

Step Three: Grasp the crank handle. Per Robell’s counsel, I resisted the urge to employ both hands. I used my left, heeding advice to refrain from wrapping a thumb around the handle; doing so typically yields severe pain (if not broken bones) in the event of a backfire.

Step Four: Heave the crank smartly upward to spin the flywheel counterclockwise. This is more difficult than it sounds. Luckily, moments before exhaustion did me in, the single-cylinder 98-cubic-inch (1609 cc) engine popped to life and began quivering, presumably with enthusiasm for my test drive.

Climbing into the tall driver’s seat is the next arduous procedure. While it’s tempting to grab the (fragile) headlamp, Robell insisted I pull myself up with my left hand on the dash and my right hand gripping the curved edge of the body. Even with a handy step pad provided, mounting the saddle is another aerobic exercise.

In case you hadn’t noticed, the steering wheel is located on this Cadillac’s right side. It would remain until well into the 1920s. By then, road design had progressed to two lanes, prompting adoption of the left-side driving position for a centralized view of both oncoming traffic and roadside hazards. Given the fact that Robell and I are both huskier than the average early-20th-Century human, we rode elbow-to-elbow in his Cadillac.

So daunting were the Model K’s unlabeled controls that I was happy to have the accommodating Robell aboard as my coach. With three levers, two pedals, and a shaking steering wheel to operate, driving this centenarian demands every limb.

Depressing the pedal on the left tightens a band in the two-speed planetary transmission to get you rolling in the 3.1:1-ratio low gear. The right pedal applies rear-wheel brakes. To complicate matters, there’s a ratchet that keeps the brakes engaged until you release them with a tap from the left edge of your shoe.

The top brass lever, attached to the right side of the steering column, controls ignition timing. “Up” is the retarded position used for starting and idling. When the 10-horsepower engine begins pounding as the Cadillac starts moving, adjusting that lever downward advances spark timing to settle down the thumper beneath the seat.

Amazingly, this Cadillac’s updraft fuel-air mixer lacks any kind of throttle! The steering column’s lower brass lever controls engine load (power), rpm, and forward velocity by increasing intake-valve lift. It’s a fascinating mechanism: The lever operates a roller rocker arm via contact with a curved plate, varying intake valve opening from 114 to 245 degrees of crankshaft rotation. Cadillac engineer Alanson Brush earned a patent for this innovation in 1904. Variable valve timing arrangements by Alfa Romeo, BMW, and Honda came decades later.

The substantial handle swinging fore and aft at the cockpit’s right side is the Model K’s gear selector. Its center position maintains neutral until you step down on the left pedal, tightening the aforementioned band to initiate forward motion. Moving the handle rearward selects reverse, also engaged by depressing the left pedal. Forcing this long lever smoothly forward tightens a band clutch operating top gear, which is a direct 1:1 ratio.

Given the fact that a heavy steel piston is thumping a full five inches up and down inside its water-cooled 5-inch-bore cast-iron cylinder, there’s more than enough vibration here to rattle your dentures. The Model K’s gait does calm nicely once top gear is engaged and the rpm drops. With the power of ten horses propelling this 1370-pound carriage, rather than one or two that drop excrement, performance had to have impressed early adopters.

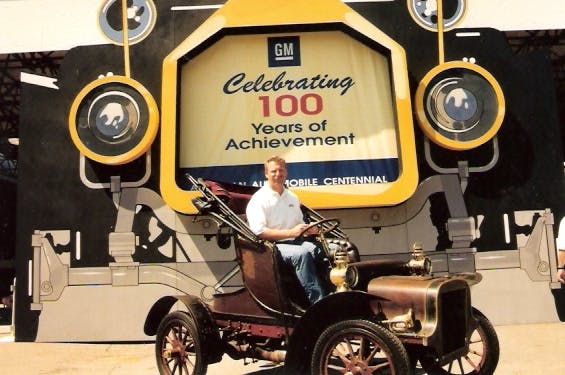

Thankfully, there is minimal traffic and no bumps in the roads circulating the Gilmore Museum in Hickory Corners, Michigan, where this Cadillac resides under national Cadillac & LaSalle Club care. After departing the club’s museum, a left turn on Duryea Drive carried us to Buick Circle, a quarter-mile-long test track.

Once the column stops shaking in my hands, the steering feels light and responsive. Robell was nervous about the right-front wheel’s wobble, resulting from the combination of a pneumatic tire supported by a steel “clencher” rim and a 12-spoke wooden wheel. Respecting his concerns we kept an easy pace, and it’s doubtful we ever topped 20 mph. This Cadillac’s alleged 30-mph top speed must have been exhilarating in period, like knocking on the sound barrier. Pedestrians would have been awestruck at time when rutted mud roads and horse-and-buggy traffic were the norm.

The engine’s heavy, shaky putt…putt…putt smooths into a relatively easy gait. Cadillac founder Henry Leland dubbed his original four-cylinder powerplant “Little Hercules” when he carried it under his arm to the 1902 receiver’s meeting that ended up converting the failed Henry Ford Company into Cadillac. That engine, proposed to but deemed too expensive for Ransom E. Olds’ use, got Cadillac off and running with its first deliveries following a New York Auto Show introduction in January 1903. The company logged 2000 firm orders from the get-go.

The Model K runabout in this test drive had a base price of $700 plus $50 for the optional leather top, or roughly $22,000 in today’s dollars.

Over a six-year production run, Cadillac built and sold 16,000 single-cylinder cars. Acknowledging that engine’s limitations, Cadillac introduced a four to power its more luxurious 1905 Model D luxury touring car. By then, Cadillac rightfully claimed to be the world’s largest auto producer. Fully enclosed bodywork arrived in 1906. William Durant added Cadillac to his cadre of General Motors brands in 1909, enabling leaps forward such as electric starting (1912) and the first mass-produced V-8 engine (1915).

The beauty of experiencing this 116-year-old crock is that it deepens our appreciation of everything that designers and engineers have contributed to modernize transportation. Best of all, Robell’s ride wears its patina with pride. Only two items have been changed over a century-plus of use—the cockpit’s floor mat required replacement after spilled gasoline dissolved part of it, and the leather soft top had to be renewed when some thoughtless leaner poked a hole in the factory-original folding roof.

Black-painted steel fenders wear the original paint applied by the Cadillac Automobile Company, at the time located at the intersection of Cass Street and Amsterdam Avenue in Detroit. There are hints of maroon paint visible on the flaking oak and poplar wooden bodywork. The tufted leather seat upholstery is worse for wear but still largely intact. Occasional polishing has kept the brass steering column, Dietz kerosene lamps, and body trim looking bright and new.

Robell, who recently retired from his Marathon Oil security director’s position, inherited this Cadillac from his grandmother Elizabeth Sherk. During their 1979 visit to the Gilmore Museum, she conveyed her desire for the car to eventually end up here.

Robell’s great-great aunt Beatrice Wynhoff purchased this Cadillac from dealer C J Bronson in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and drove it for six years. Fred and Elizabeth Sherk took possession in the early 1940s, dutifully maintaining and occasionally driving the car for decades. Robell inherited the car in 1989, donating it to the Cadillac & LaSalle Club’s Gilmore museum just last year (2021).

Robell chuckled when I guessed that his unmolested, single-family-owned, prize Cadillac might be worth a million dollars. Digging in to ascertain its true value, I found that a similar 1907 Model K blessed with a two-year restoration sold for $121,000 in 2007 at a Barrett-Jackson auction. All the king’s horses and valuation personnel at Hagerty dug deeper to arrive at this lower range—$55,000—$64,000. I stand corrected.

Clearly I’m not a valuation connoisseur. But now that I’ve driven (and started!) the car that got this marque rolling, I can legitimately consider myself a true Cadillac connoisseur.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Aside from criteria for performance and handling, that is pretty much the picture I have for an ideal collector car. It is largely original, it runs, it drives, and it has the minimal amount of restoration required to achieve run and drive. It requires interaction from the operator to operate (yes, operate, not occupy) the vehicle. More like this please

Great story, interesting car.

My only Cadillac was a 1937 Fleetwood-Bodied, Model 65, 4-door sedan. I paid $150 for it in 1961 and drove it for the next couple of years. It was big, black and beautiful, with gray wool interior. The car was totally original, including a factory AM radio. Interestingly, the radio’s antenna was made up of four or five flat, metal strips, about 1 1/2 inches wide, covered in Bakelite, strung under the driver’s side running board. The engine, a 346 cubic-inch, L-head V-8, ran great, except for a possible burned valve, that I never got around to repairing. I would often take my high school chums for an after-school ride to the local eatery, for a hot dog and a mug of root beer. The beast literally “rode like a Cadillac” and was “built like a tank”. The only downside was that it got about 4 miles per gallon of gasoline. Even at around 30 cents a gallon, it was a little costly for a high school kid in the early sixties. I miss that old beast…

It’s amazing how in a very short time the automobile advanced beyond all of these things you had to do just to go 20mph!

Growing up in New Jersey, my Father’s friend Mr. Sam Alperti (spelling?) had a 1906 Cadillac. It must’ve been the touring version as I recall it was a little longer than the vehicle pictured in this article. It always looked so fancy compared to our 1916 Buick touring car in all black. Mr. Alperti’s Cadillac had lots of brass and a cream colored body. Brown leather tufted seats similar to the ones pictured in this article.

I always enjoyed looking at that 1906 Cadillac, it’s a million dollar memory

Great story !!! I Owned 6 Caddy’s over the years , All Two Doors With White Top coat And Red Leather Inside !!!

Poorly written article. The engine was not developed by Leland, it, like the rest of the car, was designed by Alanson Brush. And it was not a Four-cylinder engine, as the article states at one point.