Mini Recharged First Look Review: Different, not greater

Out of respect for the British shop and our British correspondent, we’ve retained much of this piece’s U.K. lexicon, down to and including the tyres. —Ed.

“In sport mode it will spin the wheels from low speeds,” says Recharged Heritage’s Tom Festa. “You can try it if you like.”

“It’s okay,” I reply, “I’m not that much of a clown.”

Approximately a minute later I light up the tyres, like a clown, after turning down a side road, while testing out the hundred-or-so horsepower the electrified Mini develops in its sportiest setting.

In my defence, the road was slightly damp, and the rest of the time the Mini had no problems putting the power down through its 12-inch wheels and skinny rubber. Like other electric conversions we’ve driven, the Mini Recharged is an absolute cinch to drive.

It was conceived through a project sanctioned by Mini—as in, BMW Mini—to expand the potential of the classic Mini, in terms of both engineering and sustainability, although the latter is a complex subject. Festa made the idea a reality, bringing together the best of British-based know-how.

He’s been with the Mini brand for twenty years (later telling me he was also involved in the first R56-generation Mini-E prototypes, used by BMW to understand how people used electric cars in the real world), and pulled together the combined knowledge of Mini, electric conversion firm Zero EV, and parts and restoration specialist Mini Sport.

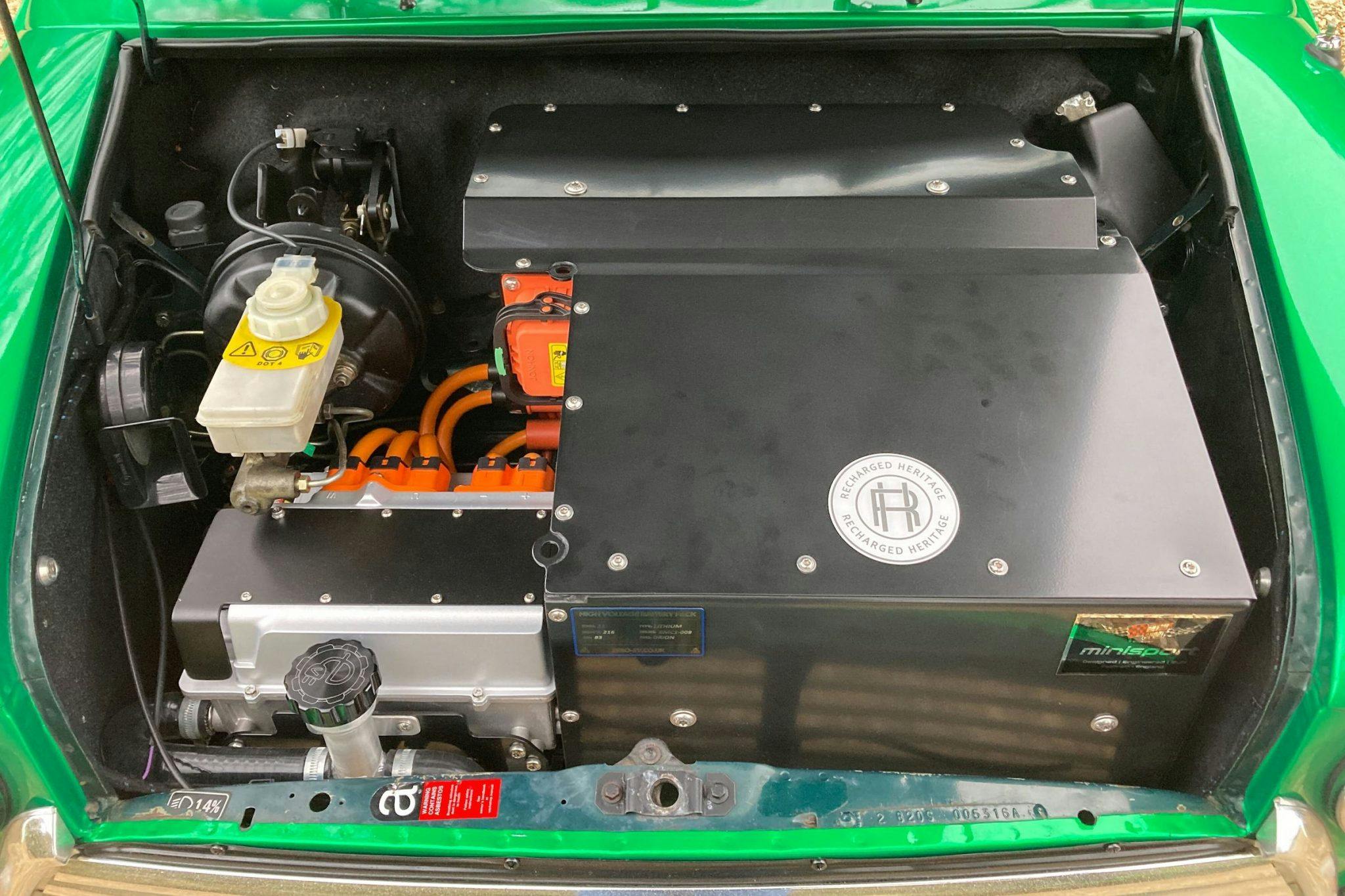

The basic package comprises 19-kWh of battery capacity split between packs under the bonnet and in the boot, plus a charger, a combined inverter and motor controller, and a 72-kW electric motor, capped at 75 hp in Pure-spec models and making the full 72 kW, or 97 hp, in Sport versions. Range is said to be good for just over 100 miles, and both versions accept a 6.6-kWh charge that means waiting three hours for a full charge using a 7-kWh wall box at home or out and about, nine hours if you’re stuck with a domestic socket.

There is also a dedicated single-speed transmission, differentiating this Mini from conversions that retain a conventional manual gearbox. This, says Festa, is because a single-speed is ultimately the better engineering solution, not least because it’s a great deal more compact. That’s important when one of the goals has been to retain the original Mini’s overall weight and its weight balance, so inherent in the character of how the little front-driver gets down the road.

Packing batteries, motors, and the like into the 10-foot shape hasn’t affected the Mini’s practicality either. In the boot, the battery lives in the spare wheel well (and comes up to the same height as the original carpet), while the charger occupies less space in the inner wing than the old fuel tank did, while neatly retaining the filler cap as the charging port.

The subframes are new, because it’s the only way to be sure everything is square, both to accomodate the new drivetrain and to ensure the thing drives straight. More notably, there are no modifications to the body—not even any new holes drilled into it —which means, in the eyes of the Driver and Vehicle and Licensing Agency (DVLA), it can retain the same registration as the donor car. That’s good for sticklers of originality too, of course—there’s nothing here you couldn’t, with time and effort equal to converting it, return to standard.

The conversion itself is entirely in-house; Recharged Heritage won’t be selling kits. The company recently announced a starting price of £62,500 for the full package, or £42,500 if you bring in a Mini yourself, and anticipates selling it in the U.S. (where those prices would equate to roughly $76,200 and $51,800)—but these full builds ensure every car is built to a certain level of quality, at Mini Sport in Burnley, and allows the shop to offer a one-year warranty on each conversion.

Festa’s demonstration car is one of the models being used for development, so it’s not technically the final product (that should be ready by February 2023), and it also has a few dings in true old-Mini style.

It is attracting attention before I even walk up to the car, though. Some of this is inherent to Minis—a guaranteed petrol-station (now charging station?) conversation starter—but part is probably down to this car’s attention-grabbing, metallic green wrap and stickers revealing its alternate power source.

Don’t read too much into the colour or the interior trim (the tartan hails from one of the many special edition Rover Minis, and lends this car its nickname): A customer can choose more or less any colour and trim combo they like. But some of the details are worth focusing on, like the custom gauge pack from Smiths, designed to replicate the original Mini’s central dials but including a drive indicator (in place of the original fuel gauge), range dial, and even a digital trip computer.

There are only two pedals in the footwell, while the manual-style lever on the floor is a simple three-position control, with neutral in the middle, pull-back for drive (as in a conventional automatic), and reverse, with a lift-up collar, in the forward position.

The rest is pure Mini, able to accommodate a surprising breadth of driver and passenger shapes and sizes, with a driving position that puts you quite far back from the windscreen and a wheel whose centrepoint aims somewhere over your head. Like Mini drivers across the ages, you’ll likely settle on a hand position somewhere around eight and four, and find yourself hunching over the wheel for every corner.

Starting up—foot on brake, twist key—is accompanied by the Morse code beeps for “mini,” and after pulling the drive selector back and releasing the handbrake, we’re off. There’s the smallest of shunts as the motor starts but low-speed manoeuvring is childishly simple, save for the need to be extra careful around pedestrians, who are often oblivious to the small, green object sneaking up on them like a character in a Pixar movie.

In regular Pure spec, Recharged Heritage has aimed for performance on a par with that of an old 1275 GT, so you’ll reach 62 mph in 11.5 seconds and top out just shy of 80. Given both figures in a regular Mini involve giving the long-stroke A-series and its four-speed ‘box absolute death, the equivalent here feels effortless and not nearly as abusive to the vehicle.

Power is managed in such a way that the car shouldn’t spin its wheels, though you’ll occasionally feel a tug of torque steer, with around 74 lb-ft through the narrow tyres. In this development car, Festa flips a switch under the dash to unleash the motor’s full 97 hp and 96 lb-ft. In doing so, he also unleashes the capacity for vulcanising rubber and giving a more aggressive shove when standing on the accelerator pedal from any speed. In this mode, the car is good for 60 mph in 8.5 sec and 90 mph maxxed out—numbers not unusual to tuned Minis, though to get this performance from an A-series you’re into the realms of considerable noise and expense.

Even in its lower power setting there’s get-up-and-go unknown to most old Minis, and the kind of thirty-to-sixty acceleration to surprise a few modern cars—remember, this 75 hp is only dealing with a kerbweight in the 600-700kg (1322–1543 pounds) range.

Response is fast and proportional to pedal input, which makes you feel like you’re driving the car and not the other way around. It’s the same story when you lift off again, with regeneration akin to conventional engine braking rather than to the opening of a parachute. The first ten or so degrees of brake pressure also engages regen. Somehow, Recharged has managed to blend this with friction brakes better than some major car manufacturers.

The Mini Recharged is refined at speed, the motor generally less … err, “talkative” than an A-series mill might be at similar velocities. Amusingly, this car still has some gear whine, something Festa says the team left in as a nod to the original. Should a customer prefer, a soundproof jacket can dull most of this noise. Still, having conversation at a normal volume is a novelty in a Mini doing 60 mph.

In true Mini style, the chassis still manages to outshine this entire new powertrain, with steering to make me think about whipping out the old go-kart cliché (dammit, I just did), near-imperceptible body roll, and Velcro grip. It’ll still misbehave like a Mini too, as a four-wheel slither around one damp right-hander demonstrates, and while you’ll still pogo along a bumpy road, Mini folks wouldn’t have it any other way.

What is unusual, if you’re familiar with Minis, is the absence of shudders and rattles, hinting at the kind of attention Recharged Heritage pays to putting these things together. I unavoidably clout a few potholes and skip over a few gnarled sections of asphalt on our Cotswold test route, but other than roll-caged racers, no other Mini I’ve driven has felt so stout.

There are still plenty of people unconvinced by electric conversions of classics, and there are plenty of good reasons to be skeptical. The cost involved is high, and the environmental benefits nebulous when many classics are used so infrequently to begin with. For some, interaction with an engine and gearbox (up to and including having to fix them occasionally) is inseparable from the experience of driving an older vehicle.

I’m one of those people, and for your reassurance, I can confidently say that the Mini Recharged is no better on a subjective level than a well-prepared, well-looked-after A-series car. All Minis are great, and this conversion only makes the Mini different, not greater.

Equally, that makes it no worse than an original, and there remain plenty of advantages to a conversion like this. Usable, repeatable, comfortable performance is one. Reliability is likely to be another: You’ll never again have to chase leaks around the engine bay.

And while not everyone lives in an urban area, usability here must be a consideration for those with the means for a car like this. While cars older than 40 years are exempt from charges like those in London’s Ultra Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ), plenty of Minis are still younger than that, and could still incur more than a decade of future charges for anyone living in an area restricted by emissions zones. The potential for combustion models being banned from cities altogether doesn’t seem far away, either, and ULEZ exemption won’t help older cars there.

Preferences and macroeconomics aside, the Mini Recharged is still fabulous to drive. And having a well-engineered, warranted, officially sanctioned conversion of this iconic classic can only make the Mini’s repertoire even wider.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Conversions are just not right.

The point of these older cars is to preserve what they were and not make a mockery of them with a modern Battery. We will have many battery powered EV models out there and all will be much better sorted and capable vs a conversion.

Look these EV models are designed to best fit a proper battery and to best use it to the max with all details touched from Aero to packaging of the components.

To be honest we should be fighting now to preserve and protect the classic cars as we are small in number and should not be excluded from using them. We preserve history and mechanical skills that could be soon lost. A good mechanic may be seen much like a black smith.

I wish large companies would better support out hobby being in fear of a poor ESG score (Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG).)

We the enthusiast may be on our own to fight this losing battle. SEMA has tried to hit back with the RPM act but it is still pending.

Be aware your hobby is on notice. They may not out right ban your cars but the fuels and oils you need can vanish and then what would be the point to keep these cars. Putting a Battery in a Duesenberg is not the answer.

We should be responsible but we also need to be reasonable.

Not better but different is a polite way to say it is not right.