Learning to drive … like a Victorian

There are so many things the modern motorist takes for granted; starting, literally, with the most basic of functions. Get into your car, crank the key, and unless it’s made in Solihull (joke!) it will probably burst into life. Well, maybe after a few jazz trombone-esque bars on the choke slider if it’s a classic. Foibles aside, most cars from the last 60 years or so are very much case of “get in and go.”

Stories from Across the Pond, as you may have guessed, hail originally from our mates over at Hagerty U.K., which you can visit here. It’s been expatriated to our site for your reading pleasure. Do indulge Mr. Cowland his native vocabulary.

You’ll then perhaps adjust the heater, turn on the radio, and maybe apply the wipers to clear the windscreen. Even on the most basic models, we are surrounded by a plethora of gadgets to make motoring something we rarely think about. Pick a point on a map, jump in, drive, arrive. It’s as simple as that.

Driving hasn’t always been like that. Our plucky motoring forebears had it much harder. When owning a motor car was much more of a novelty, and very much a luxury, the travails of car ownership were significantly more involved—as I discovered when I spent a day with Hagerty U.K.’s own 1903 Knox.

I wheeled out this wonderful machine at the track at Bicester Heritage, near Oxford, for a day of learning how to drive like a Victorian. (And before you point out the obvious, those of a driving age had lived through the Victorian era.) Not solely because I wished to return to a time when one could wear a top hat and bark orders at the ordinary people on their horse-drawn carts or bicycles, but also because, on November 7, I will be riding in the Knox on the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run. The event attracts hundreds of cars built before 1905, and marks the emancipation of the motor car—and the change in law that did away with the need for all vehicles to be driven at walking pace and preceded by a man waving a red flag.

Knox is a name not known to many Brits, having been one of many great American pioneering car makers that didn’t make the cut as the fledgling industry found its direction at the turn of the last century. But you evidently can’t lay blame for that with the quality of its workmanship. Even by today’s standards, this 118 year-old museum piece still feels impeccably engineered, with a solidity and material quality that shows true craftsmanship and heft. Beautifully made brass throttle and gear linkages would get most steampunk enthusiasts very hot under the collar, while the perfectly patinated bodywork and upholstery, clearly from a high-quality, older restoration, makes even just sitting in the thing very much the “Gentleman’s Club on Wheels” that I’m sure those well-heeled pioneers were looking for.

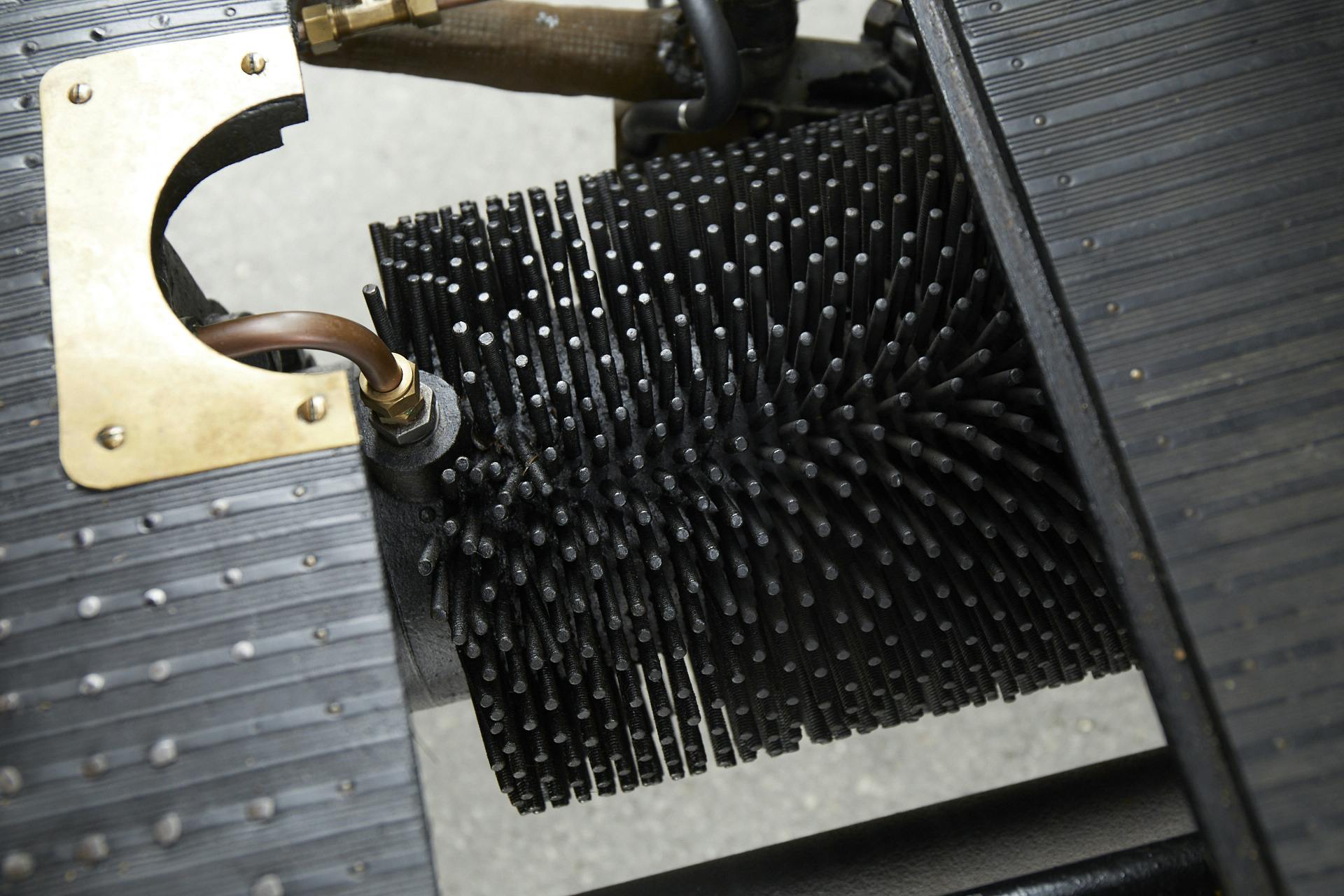

The Knox Automobile Company was established in 1900, building 15 cars in its first year. When new the “Knoxmobile” sold for $1350 in contrast to the Ford Model F which sold for $2000. The specification of the Knox is fairly unique. A single cylinder of some 2575 cc shakes and bucks with the unreciprocated urgency that you might imagine. A crazy 5-inch bore and 8-inch stroke moves a lot of metal with each lazy revolution, after all. The cylinder itself sits with an ingenious heatsink, resembling a huge metal hedgehog, created by the precision drilling and tapping of some 1750 threaded studs, making this bonkers creation one the earliest aircooled progenitors. If you’re reading this as an owner of an old Tatra, Beetle, or 911, say “hello” to your great, great, Grandfather.

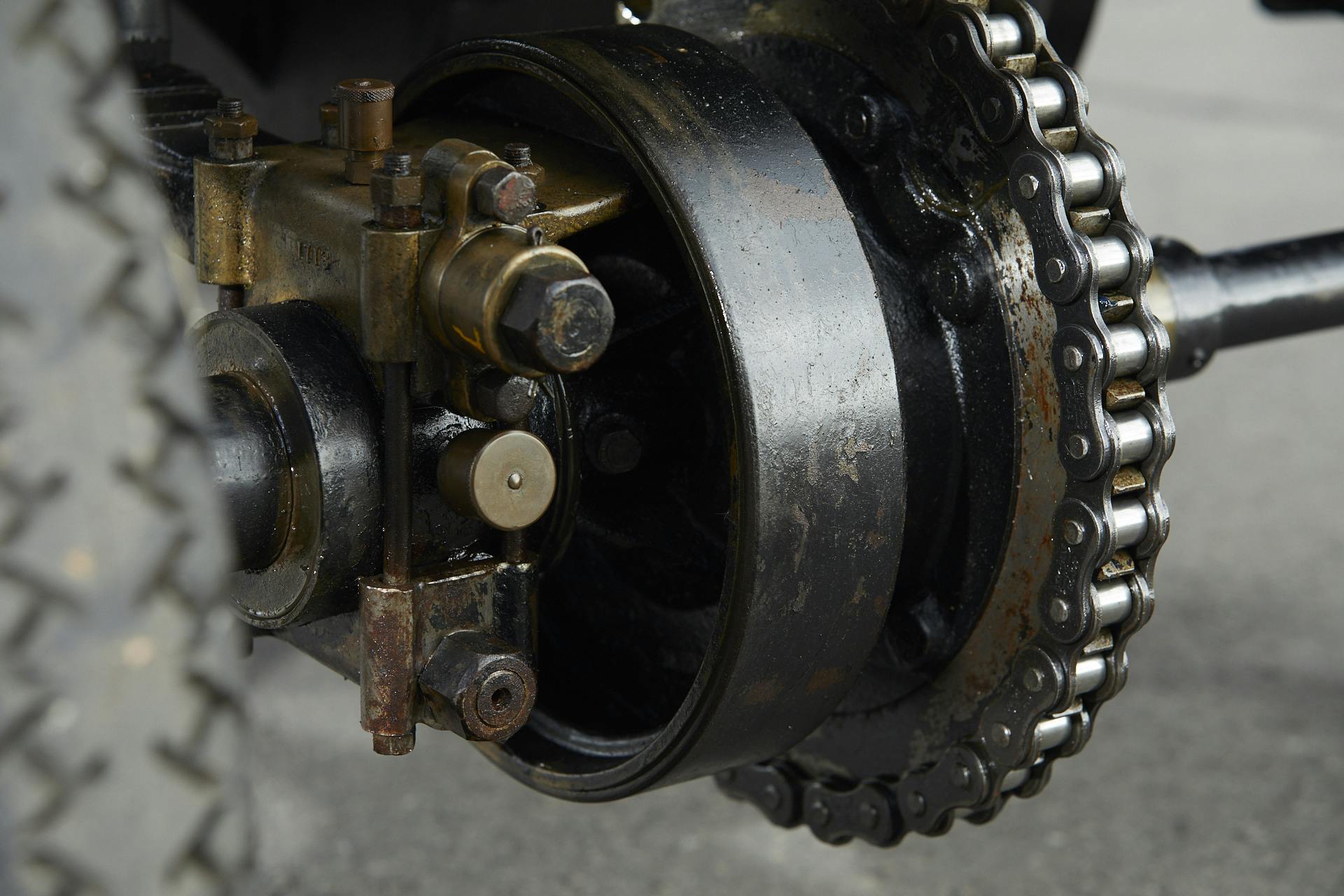

The engine is paired with two epicyclic gear ratios, making power take-up, via the chain to the rear axle, very similar to any ancient automatic. Gear changes are operated via a beautifully machined lever by your left hand. At zero throttle, the drive is disengaged, then you open the “power” to get the thing moving.

On that note, there are around six fairly asthmatic horses residing within that prickly powerhouse, with the ability to open up the exhaust baffles via a simple foot switch to liberate an additional small foal to assist you on the hills. That’s right, even in 1903 you could specify a switchable sports mode on your car’s exhaust.

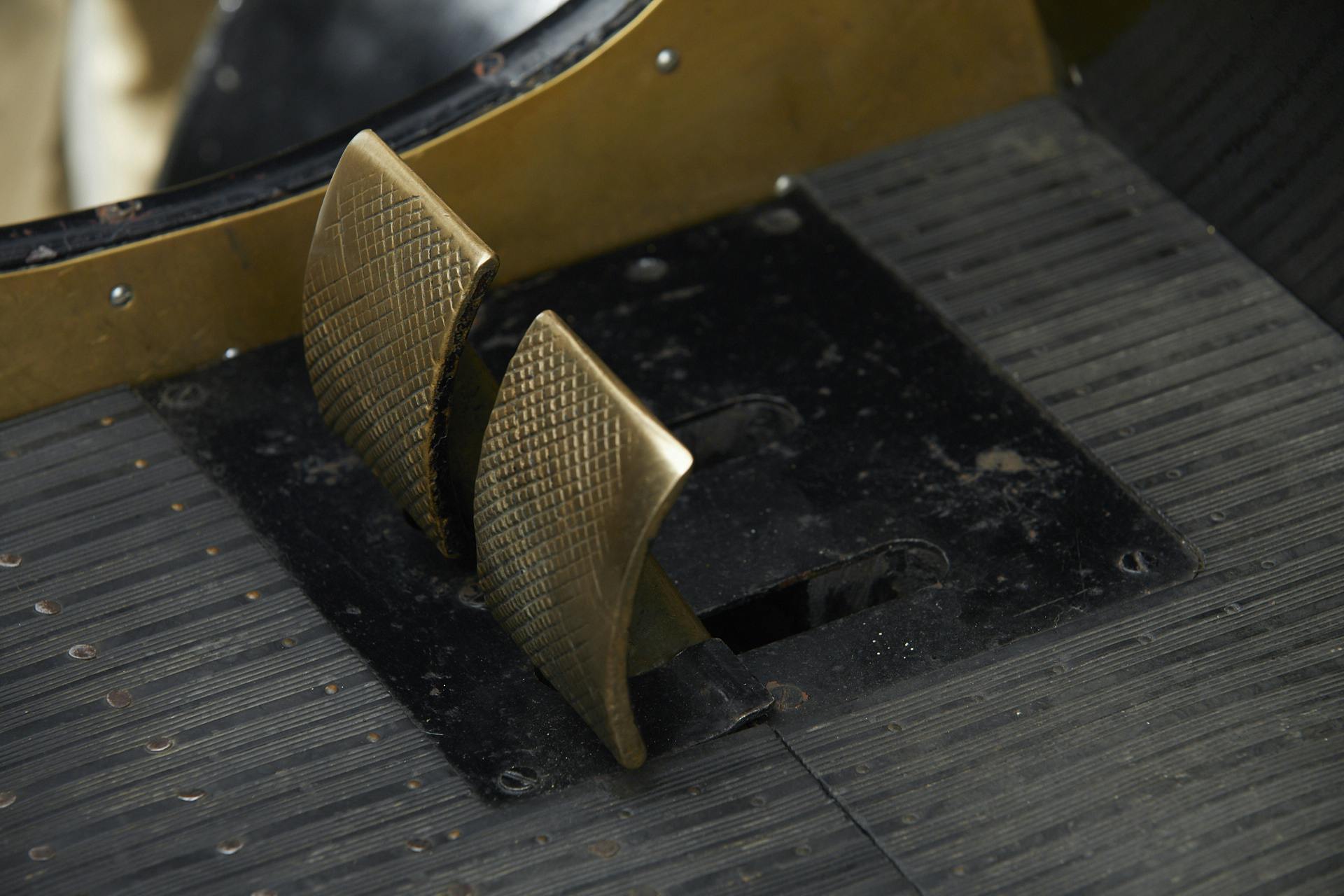

Everywhere you look on this car there are beautiful details, but nothing functions as you might think. Throttle is by your left hand, as is selecting either one of the gear ratios. The right hand pedal is a nod to what followed by being a braking system on the drivetrain itself, whereas what you might think would be the clutch is actually reverse gear.

The biggest difference is the steering system. Although several manufacturers had already adopted the steering wheel by 1903, Knox clearly wasn’t having any of that new-fangled tomfoolery, instead opting for the tried-and-tested tiller system to effect steering movement. One can only imagine that reading “steers like a boat” in contemporary Autocar reviews of the day wouldn’t have been quite the slight that it is now.

The start-up procedure for the Knox reads like one of Tolstoy’s lesser-known sequela. Greasers and oilers must be set in motion, fuel must be set cascading via the sheer power of gravity towards the comically small carburetor, before the magic of electricity is sent coursing to create that first explosion. Can you imagine how other-worldly this must have all felt in period? As your attention flits between the wick-fed oil-burning headlamps and the once cutting edge technology beneath, (which, in essence, hasn’t really advanced a full century or so later) you start to realize what an exciting time in automotive history the early 1900s must have been—a juxtaposition of old and new thinking.

Guiding me through this extensive list of pre-flight checks was Gregg May, the car’s custodian, engineer and owner of Autohistoric. Charged with maintaining and restoring the Knox, Gregg’s sage knowledge would be invaluable throughout the day—particularly when it came to the daunting prospect of bringing it to life using its substantial starter handle. Get it right, and this charming little conveyance will cough quietly into life. Get it wrong, and you’re going to get 6.5 horses violently kicking back through your arm—and that’s never going to end well. I listened very intently to everything May had to say.

As an additional insurance policy to ensure neither the car nor I got hurt, Hagerty also wheeled out my old friend, James Wood. Driving under Hagerty colors in all manner of racing events on the classic car calendar, including Goodwood Revival and the Monaco Historic Grand Prix, “Woody” is your go-to man if you’ve got a collectible or unique classic racing car that you’d like to see entered and driven competitively in a blue riband event. As a hugely experienced racer that’s driven some of the world’s rarest cars, he’s the guy that generally gets your motor on the podium—and then hands it back in the same shape it started the day in. He’s also an MSA “Grade A” driving tutor, too, sharing his skills with some of the world’s greatest pedalers to help them shave precious tenths from their lap times.

Woody kindly took me for a few laps of the Bicester Heritage track to help me to acclimatize to the Knox’s unconventional driving style. Watching intently, we drove for a few minutes before it was my turn to perch my 6-foot-4-inch frame on the Chippendale.

Whether it was the excellent tuition, a drummer’s ability to make your four limbs do anything you ask of them, or the inherent simplicity in the Knox’s basic design, the subsequent test drive was a pure delight. The hand throttle proved to be very linear and smooth, with just a little dip needed for a change into second. The tiller was a direct and faithful servant, providing really quite precise inputs with very little play, and the clever leaf spring arrangement made for a reasonably decent ride on the smooth track surface. The driving position is, well, commanding, giving an outstanding vista, while the brakes—if somewhat alarming by modern standards—boasted decent modulation and, technically, even retardation.

The pleasant surprise is that this 1903 car does exactly what you ask of it. All its driver has to do, on today’s roads, is you leave sufficient margin to allow for the car’s modest performance. Within two laps we were really starting to motor, and by the third, I’d even started liberating the extra half-horse on the straights, meaning we were knocking on the door of around 25 mph!

This is what amazed me most about the Knox. I’d expected the idiosyncrasies, I’d expected the noise, the lack of creature comforts and the carriage-quality ride, but I hadn’t expected it to be so intuitive, so useable or so engaging. Once you’ve managed to get it started, this really is a car that you can drive to the shops, the pub or maybe even on a wild road trip. It’s as fit for purpose and as entertaining to drive in 2021 as it must have been in 1903. We may have windscreens, stereos, and steering wheels these days, but you have to hand it to those Knox boys, they had made a machine that offered sheer driving joy, before most of our ancestors had a clue what that might even mean.

So where does one take a 1903 Knox on a wild road trip in 2021? Well, in the case of Woody and I, we’ll be cranking the starting handle at this year’s 125th London to Brighton run. It’s no exaggeration when I say it will be an honor to celebrate the emancipation of the motor car, and the change in law that did away with the need for all autos to be driven at walking pace and preceded by a man waving a red flag. To toast this new-found freedom, the Victorians promptly organized the first “cruise” from London—and raced off in their Flints, Darracqs and De-Dion Butons for crumpets and Earl Grey in Brighton in the afternoon, setting a wonderful precedent for us all to follow.

The Knox will line up against hundreds of its chronological contemporaries in the mist and dark before dawn breaks across London. I can’t wait to tell you how we get on. I just hope I can remember how to get the thing started.