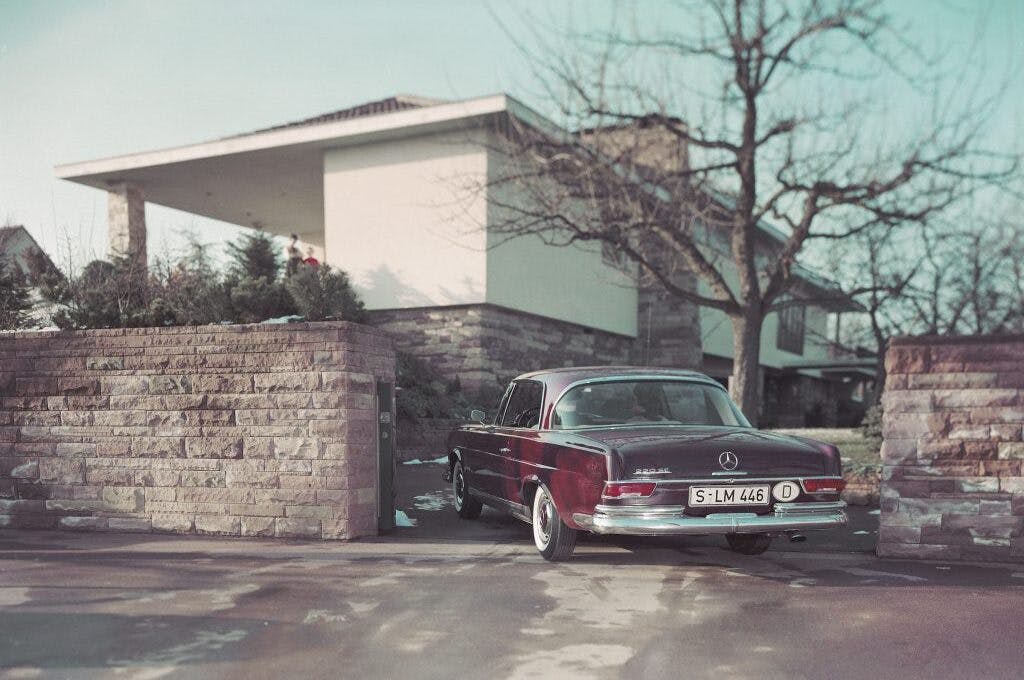

Driving the Mercedes that defined “luxury car”

It takes a few beats for me to realize the farmer is not, in fact, angry that we’re blocking one of his access roads. Quite the opposite in fact.

We’re definitely in his way, even though I’ve parked the 450 SEL as far to one side as possible in the wide junction to allow his clattering old tractor to pass unhindered. But as I get closer, with my best “we’ll be moving soon” body language on standby, I realize that he’s actually trying to offer compliments on the large, dark blue saloon.

Five decades on from launch, the W116-generation Mercedes-Benz S-Class still has gravitas. Especially for sun-wizened grape farmers within a stone’s throw of Stuttgart.

The idea of an S-Class was not entirely new when the W116 debuted in 1972. There were big Mercedes Sonderklasse (“special class”) saloons before it, a lineage beginning with the W180 “Ponton” of 1954. The Ponton was a grand and somewhat upright model named for its unbroken unibody styling, after decades of cycle wings and running boards, followed by the “Adenauer” W189 in 1957.

This time the name informally evoked the first Chancellor of Germany, Konrad Adenauer, who was rarely photographed without one iteration or another of W189 in the background. Two generations of “Fintail” (W111 and W112) followed—neither of whose should need its nickname explained—while finally, between 1965 and 1972, came the W108 and W109 strich achts or “stroke eights.”

But by the end of the 1960s, the strich acht was due a successor, and while the W116 S-Class that replaced it had no catchy nickname, it did have a very clear brief: Take the luxury model in a new direction for design, driveability, and, as was becoming ever more important at the time, safety.

Mercedes implemented an entirely new suspension system, with a control-arm setup at the front (lower wishbones with single upper links connected to an antiroll bar), using lessons learned from the C111 development vehicles. Zero-offset steering geometry—good for stability, but something that can increase steering effort—was justified on the grounds that all models would use assisted steering anyway.

Mercedes’ swing axles were safer than most rear suspension designs of the period, but for the W116, they finally made way for semi-trailing arms. Conventional springs suspended most models, but the 450 SEL 6.9 traded that for hydropneumatic suspension. Autocar’s technical report in 1972 commented that the company made little fanfare about noise-suppression measures compared to its predecessor—but also noted that Mercedes’ improvements in structural design and attention to detail meant that mitigating measures like fat rubber bushes were no longer necessary to isolate vibrations.

The new cabin was as padded as the Michelin man, with squeezable surfaces everywhere from the screen pillars to the wheel, the dashboard to the sun visors. Mirrors featured anti-dazzle settings, rear doors were equipped with child locks, and door handles were flush-fitted, to avoid the risk of contact in an accident. If any of this sounds routine now, it wasn’t fifty years ago.

The range included inline-six and V-8 power units, varying from the 160-horse 280S to first 350 and then later 450 SEs, the latter good for 222 hp and 278 lb-ft from its 4520-cc overhead-cam V8. Top of the tree, though, arrived in 1975, with the mighty 6.9-liter.

Still badged 450, with “SEL” denoting a longer wheelbase, the 6.9 was derived from Mercedes’ 6.3-liter V-8, each cylinder bored from 103 to 107 mm but retaining a short, 95 mm stroke. High revs weren’t the aim here, though; the red paint on the tachometer started at only 5200 rpm, and the 6.9 made a 282 hp maximum at a relaxed 4250 rpm. Geared for 140 mph, it could also bludgeon past 60 mph in only 7.2 seconds. A handy 405 lb-ft of torque rendered the 4800-pound 6.9 mostly unhampered by its own mass.

As the farmer will try and convey in a short while, the W116 has magnificent presence. Friedrich Geiger’s shape took cues from the earlier Mercedes saloons penned by Paul Bracq, but like the R107-chassis SL and C107-chassis SLC that debuted a year earlier, and the W123-generation E-Class that followed later in the 1970s, stacked headlights made way for horizontal lamps, a motif echoed in the ribbed tail lights (designed to reduce dirt accumulation), and in several horizontal character lines breaking up the side profile.

It’s large but not overwhelmingly so, even in this long-wheelbase form. Even for its grandest models, Mercedes operated on the basis that its cars should be no larger than necessary to meet their packaging needs, and dedicated little space to unnecessary styling flourishes or ornamentation.

Conventional W116s stretched to 195 inches, with 3.9 inches added to the wheelbase for SELs. American versions were the longest of all, but only on account of impact bumpers vast enough to serve as an emergency landing strip for small aircraft. They added nearly a foot.

That safety-first cabin might be awash with plastic, but there’s nothing synthetic about the experience of opening and closing the doors. The action of the button and feel of the handle are unparalleled, and as you close the door, there’s something primally satisfying about the combined whump of the door closing—with no reverb or vibration to imply anything close to tinniness—and the clack of the door striker, which could probably be used to connect train cars.

Hard-wearing cloth covers the front seats and rear bench. The front pews are wide and flat but still promise total comfort, and have that key characteristic of all the best seats, in that they don’t need much messing with to find the perfect position. The dashboard is an object lesson in everything you need and nothing you don’t; large, clear controls, grouped sensibly, and with wear rates to even minor switchgear that you could measure on a geological timescale.

The dials, too, are perfectly clear, but one number in particular stands out in this 1977 car: 647,800. It’s the odometer reading, in kilometers, and it’s showing the equivalent of more than 400,000 miles. Peter Becker, from Mercedes-Benz Classic Communications, explains that the car was formerly part of an industry association fleet and was meticulously maintained both then and since Mercedes itself adopted the car. There is no better advertisement for both building a car properly to start with, and then maintaining it correctly; if I’d peered inside and the odo had been reading a hundredth of that figure, I’d have been no more surprised.

As the car warms up, Becker leaves me with a warning to be careful out of junctions. The 6.9 liter-engine paired with its limited-slip differential is more than enough to trouble the efforts of 215-section tires with a balloon-like profile over 14-inch wheels. And sure enough, at the first brisk getaway—to avoid losing the photography car in traffic—there’s a screeeee from somewhere aft. Even so, all feels so calm from the driver’s seat that the noise could have been from a different car entirely.

Winding through urban areas the main sensation is one of more space to move than expected; the SEL might be more than 16 feet long, but at over six feet wide, it’s slimmer of beam than modern equivalents, and doesn’t require a sharp intake of breath every time the road tightens.

The heavy throttle needs firm pressure to get the desired result, leading to those occasional sporty getaways when you misjudge it, but the S-Class creeps easily through traffic and hangs on the coattails of modern traffic without getting flustered. The steering is also easy-going—it’s not fingerlight, but requires little conscious effort to direct.

The 6.9 has a rich character but is naturally muted for this purpose. AMG-style fire and brimstone is absent. In their place, a kind of reassuring rumble, which does build in intensity with a piledriver-like intake noise towards the redline. Still, it’s never enough to disturb conversational volume. Or, in my case, the German pop music emanating from that wonderful, period Becker Mexico stereo.

Ask for small throttle openings and the 6.9 surges proportionally forward. Demand more, and the pauses get larger, as the torque converter spins up and occasionally allows a lower gear for even more acceleration. Never with a thump; if the noise is judged to allow deals to be brokered uninterrupted, then acceleration and gear changes are metered out to avoid spilling the champagne toasting a successful business venture.

Titans of industry might need to hold on tighter in the corners. A good chauffeur will always try and keep the vehicle right and level, but present a motoring journalist with a couple of closely stacked and perfectly-surfaced S-curves and the temptation is often too great.

In deference to age, mileage, and value I abstain from true silliness, but like a charging sumo wrestler, the S-Class has moves unexpected for its size. Much like the later W201 190E we drove in 2021, the W116 seems to shrug off its straight-line softness as soon as there’s a corner in sight. The nose goes where you put it, and while the photos betray high roll angles, the chassis still feels like it has grip to spare.

Gearbox in sport setting for the best response, you need maybe only half throttle on the exit of a tight turn for those 400 pound-feet of torque to overcome the rear tires. Losing traction sounds more dramatic than it feels, requiring just a small lift for the rubber to hook back up. Around faster corners, the car shows genuine balance too, moving with all four corners rather than leaning hard on the front and unloading the rear, as the chassis does in slower turns.

The stopping system is more than suited to harnessing two tonnes of German steel. A driver deft of foot can pull off wonderfully smooth “limousine stops” in normal driving, but despite tiny discs crammed into those 14-inch wheels, the brakes don’t protest at more frequent, more insistent prods when winding up and down hill for photographs.

If there’s one surprise, it’s that the ride can sometimes feel a little sudden. The fact that this is notable only sometimes is characteristic to hydropneumatic setups, which lull you into a false sense of security with feathery softness before making hard work of certain types of bump. We didn’t have time to seek out any Autobahnen, but if the ride doesn’t settle down to perfection there at three-figure speeds (where those brakes should further reassure), you can brand me with a three-pointed star.

By now the cabin is getting warmer than the engine, and after adjusting a few knobs and levers, the air conditioning releases a wintry blast from the vents. The driving position has been comfortable all afternoon, and the S-Class eases back into cruising as happily as it had put up with being hustled around a few curves.

It’s tempting to dismiss modern advances when putting old in the context of new, but so many of a modern luxury car’s fundamentals are right there in the original W116 S-Class. Its 2022 equivalent is, of course, more comfortable still, quieter, more spacious, and easier to drive—but by smaller margins than you might expect.

Only in performance do modern limos significantly outpace their ancestors, particularly with the advent of electric propulsion, though I suspect all that means to the average chauffeur is that they use a smaller proportion of available power than ever before. Nobody keeps their job by launching their clients to 60 mph in the blink of an eye, whether the car can do it or not.

Offered the chance to do significant distance in a luxury car, I would only be compelled to choose new over old, assuming I was paying for it myself, by fuel efficiency. Mercedes reckoned on around 18 mpg for a touring figure, and as little as 12 mpg in normal use. Assuming this W116 has done 15 mpg over its 400,000-mile lifetime, it’s imbibed more than 26,600 gallons of unleaded over the last 45 years. Or about three and a half articulated fuel tankers’ worth.

The best part of five decades ago, and for a certain kind of client, fuel consumption would have been of little concern, of course. On modest trips, and for an enthusiast with reasonably deep pockets, the W116’s thirst may not matter today, either; the privilege of driving this luxury icon is as grand as it ever was.

The qualities of a luxury car are timeless. Mercedes had honed them before the car it called the S-Class came along, and it has refined them since. But it was the W116 S-Class, and the 450 SEL 6.9 especially, that defined them.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

These are such beautiful cars.

Incidently, wheel design and tire sizing were part of the appeal and beauty of cars back in the stone age when rubber bands strapped to satellite dishes were not yet considered. The right combination could indicate luxury and comfort or performance and aggression.

Cars such as these are measured in Smiles Per Gallon, as podunk as that may sound. Indeed, the cost of the fuel and the cost of the car; one is no more a concern than the other to those of such wherewithal.