Driving the Light Car Company Rocket, Gordon Murray’s original hypercar

Before Gordon Murray created the McLaren F1 or even contemplated its successor 28 years later—the new T.50 hypercar—he sat down with his friend, Chris Craft, and over a pint of beer the two men started dreaming.

Craft was a race driver who’d made his name in formula cars and sports cars, and on the back of a coaster mat he and Murray sketched out a vision for a road car that was a clean-sheet design, one that sought to ritually burn every rule book in existence. The result was the Rocket, from the newly-formed Light Car Company.

By this time, Murray knew a thing or two about building successful racing cars. He had masterminded two world championships for Brabham and four for McLaren, in the Senna and Prost heyday. So it’s fair to say that the Rocket was created with a singularity and sense of purpose that is rarely found.

It’s also fair to say that the Rocket and small, light, engaging cars of its kind are arguably more relevant than ever before. We are living in an age where the mainstream makers of performance cars have become hooked on power, downforce and lap times, in the process forgetting that, on the whole, most of us spend most of our time driving on the public roads—where they have these things known as speed limits.

I guarantee that you’ll have more fun, and experience a greater range of sensations, driving a 837-pound Rocket at the national speed limit than you will getting a near-two-ton hypercar airborne over the Nürburgring’s Flugplatz.

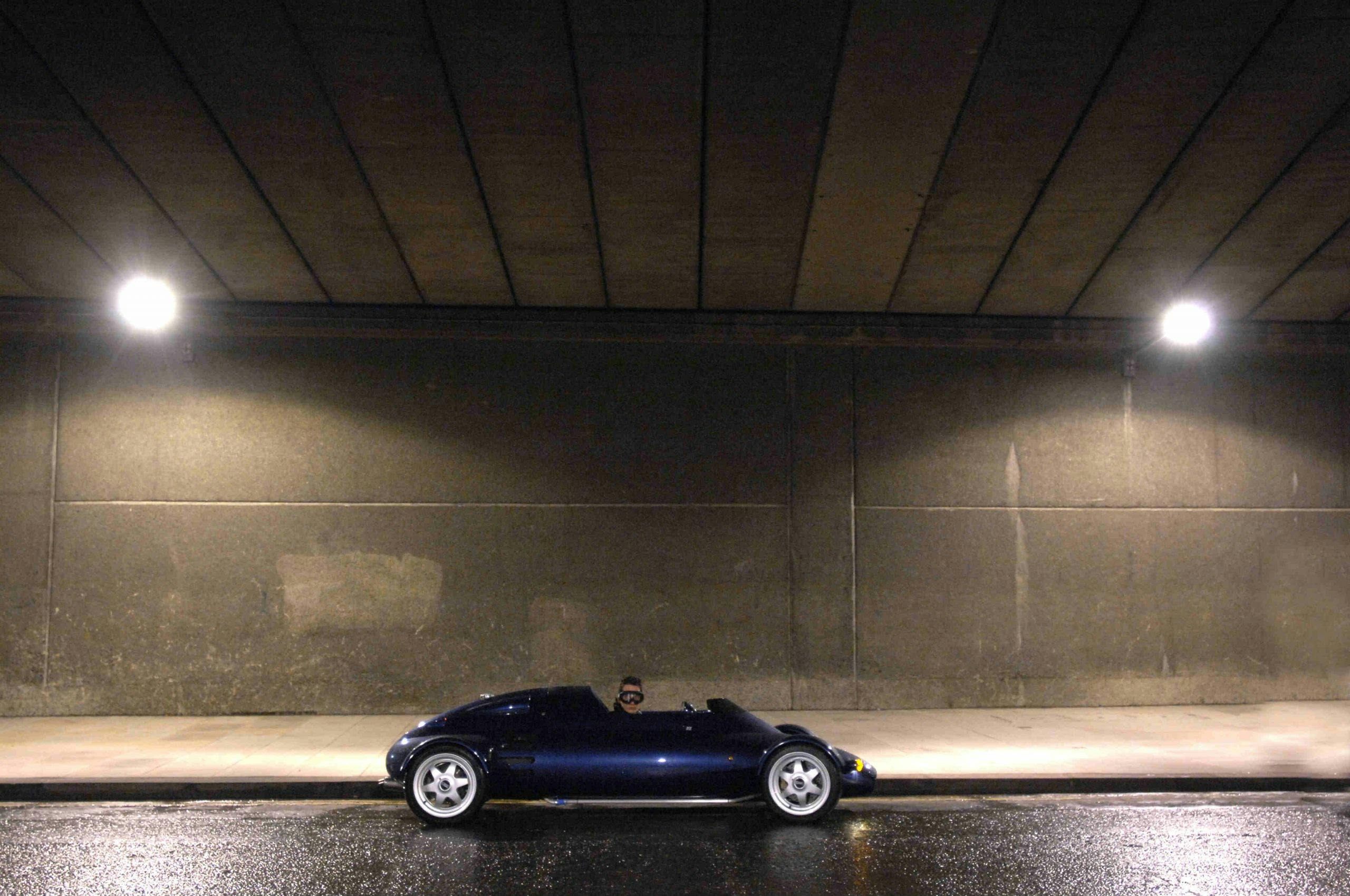

I once spent several days driving a Rocket around the South of England, treating onlookers in London to the slither of a cigar-shaped machine, scaring the wildlife around the roads of Ashdown Forest, in Kent, before, finally, scaring myself silly on one of my favorite roads, down to Beachy Head.

That was back in 2007, and I remember it like it was yesterday. The Rocket is one of those cars that leaves more than a lasting impression; it brands your brain as though a hot iron has been passed inside your ear and seared against the hippocampus.

I was lucky to get a go. After Craft and Murray launched the Rocket, for the 1992 model year, it didn’t exactly reach the stars. Few people wanted a sports car that aped 1960s Grand Prix machines, was as light as a pair of Keds and offered all the weather and crash protection of a paper bag. Especially at the price: £38,800 was twice the price of the fastest Caterham Seven, save for the bananas JPE. Fifty-five Rockets were built in total.

Is there another car that’s so singularly focused on the simple act of driving for, well, driving’s sake? If you didn’t have pockets, you put everything in a bag on the back seat (yes, it’s a tandem) or left it at home. Forget about charging a phone or using it to navigate or stream music. The only thing to focus on is the rev counter; even the speedometer barely warrants a glance, because everything is so instinctive in this car.

There was something immensely satisfying about emptying your mind of all distractions and immersing yourself in everything the Rocket had to offer. Let’s face it, sometimes all we want when we climb into a car is to get away from it all. And in that respect, the Rocket took you to another dimension.

The shrill shriek of its 11,000-rpm Yamaha bike engine, uninterrupted shift of the fully-stressed, Weismann five-speed sequential gearbox, peculiarity of messing around with its two-speed final drive, rampant rate of acceleration, and oh-so delicate response of the nose as you glided from twist to turn was at once intimidating and intoxicating.

There were things that a few days’ driving couldn’t tell you. For example, the unnervingly light nose would always bite when you steered into a curve but you were never certain that it would. And with the weight of the engine set so far back in the spaceframe chassis—just 46 pounds, naked—I was conscious that it would take just one misjudgment of a high-speed corner and they’d be picking man and machine out of the trees for weeks to come.

At this point, I should be honest. Driving a Rocket was a pain. You’d have to change your shoes, put on a waterproof jacket, insert earplugs, add sunglasses/flying hat or goggles/helmet (your choice), then climb in, adjust seat and Willans belts, fasten yourself in for the ride of your life, dip the clutch and fire her up. Only then would you realize you haven’t put the Hella headlamps up, and if you want to live, you really ought to. So you had to clamber back out, flip up the carbon-shrouded headlamps – held in place by dapper little Eibach damper arms—and repeat the whole process.

Then you’d stall. With no flywheel effect, the Yamaha’s revs would rise and fall like a very large, very angry, methanol-powered lawn trimmer, and the clutch would bite with all the subtlety of stepping onto a live rail. It was no Toyota Corolla. Neither, then, was it intended to be.

I hear rumors of late that plans are afoot for the Light Car Company and, perhaps, the Rocket. Companies such as Ariel and BAC have shown that there is an appetite for out-there cars but somewhere sits a line so fine it’s almost invisible, between bringing back something from the past and creating a vision for the future.

For the few that are fortunate enough to own a Rocket, however, it remains one of the ultimate cars in which to lose yourself. And for collectors, surely the ultimate accomplishment when it comes to bragging rights would be to own the Rocket, an F1, and the new T.50.

Via Hagerty UK