Vision Thing: There’ll be no spinning in graves, actually

It’s perceived wisdom that these days that an SUV a day keeps the administrators away. As if the cost of selling sporting machinery involves a Faustian pact with raised suspension and all-wheel drive. Look at the Aston Martin DBX, which is obviously just about keeping the lights on in Gaydon. Elsewhere, McLaren has so far resisted the temptation of such an easy cash grab. Contrary to popular belief, the Cayenne didn’t save Porsche; the Toyota Production System and the 986 Boxster/996 911 twins did, being essentially the same car from the B-pillar forward. Jaguar, refocusing on its core brief of sporting luxury, has cancelled the J-Pace, a large SUV that would have sat above the F-Pace.

Ferrari, the most profitable per unit OEM on the planet, doesn’t need to build an SUV but is doing so anyway. So much for Enzo Ferrari’s comment that it would build one less car it could actually sell. If the leaked images of the so-called Purosangue are anything to go by, it’s going to undo Ferrari’s recent aesthetic resurgence.

Shareholder appeasement has a price. Et tu, Lotus?

Colin Chapman’s old cliché of “simplify, and add lightness” was born not just from his exceptional talents as an engineer, but from necessity. Austerity in post-war Britain meant materials shortages. Chapman had to zig where others zagged, doing more with less. After several successful aluminum club racers, his first roadgoing car, the sylph-like Type 14 Elite had a GRP (glass-reinforced plastic) monocoque whose shape was fettled by aerodynamicist Frank Costin and an engine repurposed from a fire pump. Exceptionally light on its feet at little more than 1000 pounds, the Elite was fast, slippery and economical but critically fragile—a criticism that many would later level at Chapman’s Grand Prix machines.

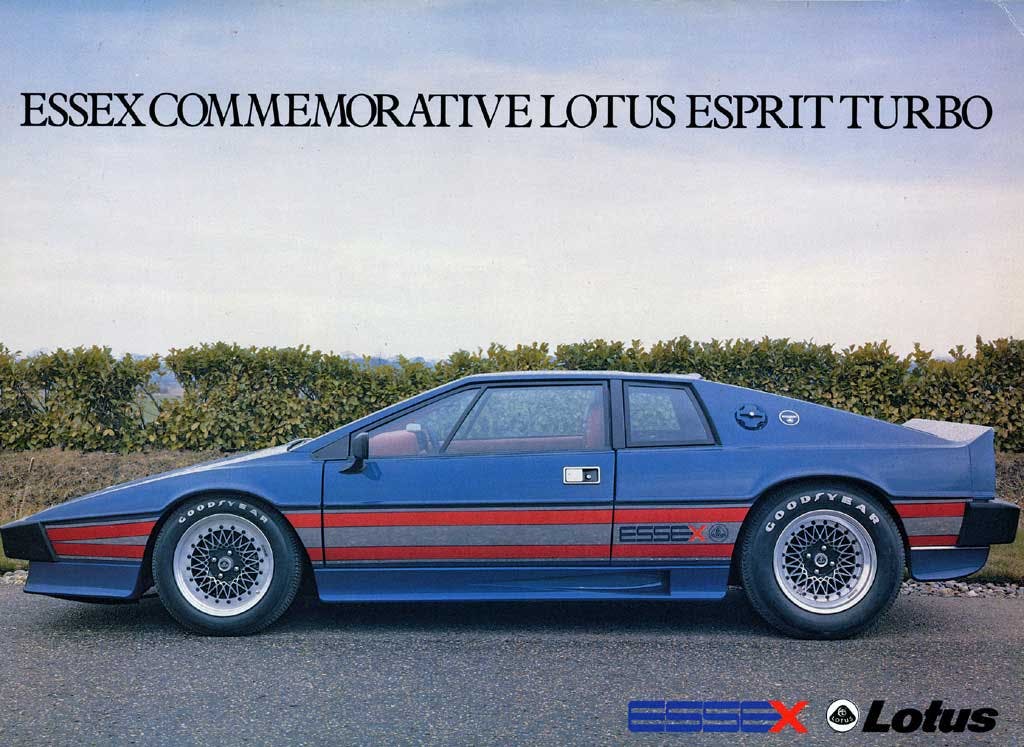

Subsequent adherence to GRP construction meant skinnier cars, but like all the best ideas it had unforeseen consequences. Plastic body work is typically 5-6 mm thick as opposed to less than a mm for stamped steel, which meant proprietary seals couldn’t be used. For the 1975 Giugiaro-designed Esprit, the size of the moldings meant separate top and bottom sections had to be laid up which led to the characteristic black line around the car where the two halves joined—a feature shared with its sister car, the Lotus developed DeLorean DMC12. (And also, curiously, with the Ferrari 308 which first appeared in 1975 with GRP bodywork before switching to steel in 1977.)

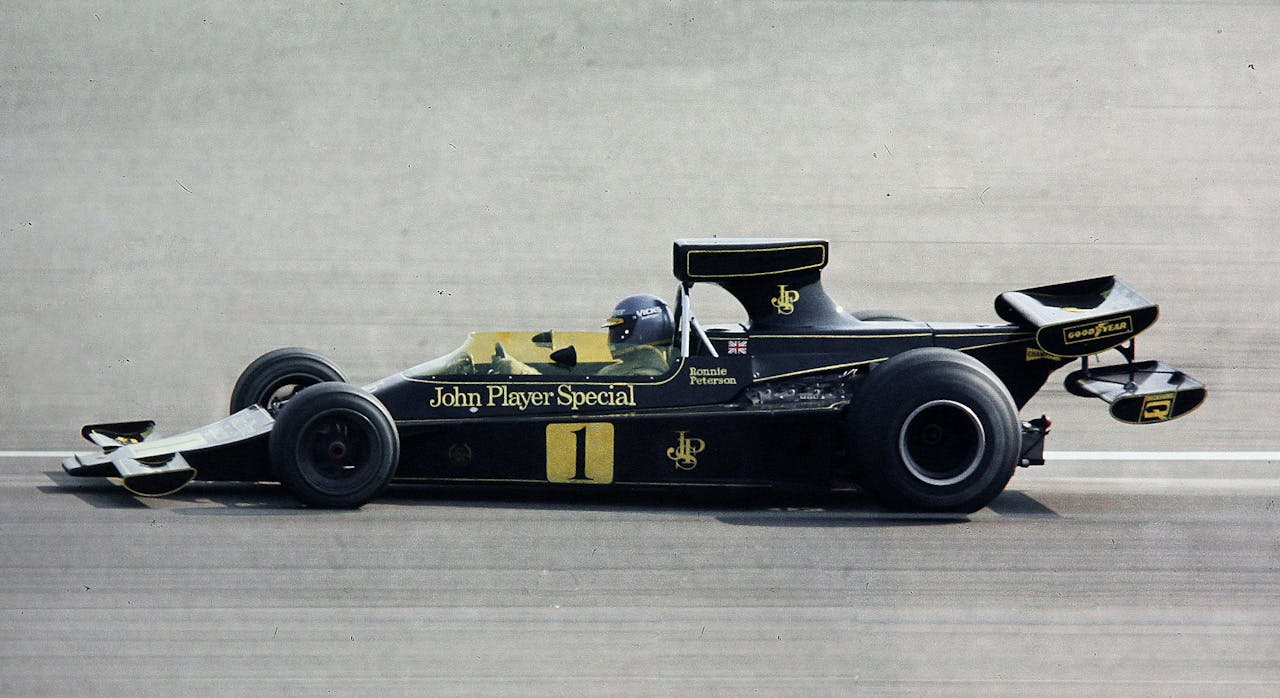

So Lotus was all about frugality of construction and engineering clarity, right? Not exactly. The revolutionary Lotus 72 F1 race car wasn’t a success until its suspension was redesigned to remove anti-dive and anti-squat geometry. That car’s eventual replacement, the Lotus 76, had a biplane rear wing and electro-hydraulic clutch operated by a button on the gear shift. This is in 1974, mind you. It was an ignominious failure. That car’s successor, the ill-fated 77, was designed to be adaptable to any race track; its complication meant it couldn’t be adapted to any of them. Mario Andretti wore out the Hethel test track turning the ground effect Lotus 78 from a bright idea into a winner.

Chapman was a fearless innovator. But if ever a man’s reach exceeded his grasp, it was him. Ultimately, something else motivated Chapman even more than out-innovating his rivals or winning motorsport races: money, that perennial flame.

Humble beginnings meant Chapman always had an eye on the financial side of motor racing. He talked Ford into bankrolling and powering his 1962 Indy 500 entry (the Lotus 29), and in 1966 convinced them to pay for the development of the engine that would democratize and rule F1 for the next two decades—the DFV. When F1 allowed corporate sponsorship from 1968, Chapman couldn’t repaint his cars fast enough. He was constantly struggling to get his road car business on a secure footing.

Seduced by the size of oil trader David Thieme’s money truck in 1979, Essex Petroleum stickered Esprit Turbos and Falstaffian F1 launches at the Royal Albert Hall became the Lotus norm. At least, right up until Thieme was indicted for fraud in 1981. When it came to his involvement with DeLorean, did Chapman half-assedly reskin the Esprit and pocket the rest of the British taxpayers’ cash? Well, the FBI were certainly sniffing around when Chapman met an untimely death in 1982, aged just 54.

Which brings us to the Eletre, the long teased hyper BEV SUV from Lotus. Something about hell freezing over and cats and dogs living together. Non-name aside (Elektra was right there!), how on earth can the company responsible for those glorious pond skater like racing cars justify this 17-foot-long technological behemoth?

The Eletre not a product of the Lotus mothership in Hethel. It was designed at the newly branded Lotus Tech Creative Center, previously the covert Geely Global Studio in Coventry, the U.K.’s Motor City. This in itself is not that unusual, as most OEMs have more than one studio; there was a gold rush in the Eighties and Nineties to open hip new studios in California (in the mold of Toyota’s Calty Design Research center, opened in 1973) as car companies recognized it as one of the world centers of car culture and the outsize influence CARB legislation would play in new product development. What is unusual is that Lotus made no secret of this fact; manufacturers are usually deliberately vague as to what was designed where, for fear of inauthenticity. I’ve certainly heard plenty of unprintable rumors in my time. Coventry and the Warwick environs are the centers of autonomous vehicle research in the U.K.—Lotus recently opened a campus at Warwick University.

So it’s no surprise, then, that the Eletre features pop-out LIDAR sensors to go with other animated exterior features, visible active cooling vents and charge port door among them. Knight Rider Pursuit Mode style pop-out appendages make great TikTok content but have design implications in terms of long-term reliability, durability, complexity, and added weight. On top of this the fact that Lotus is in the process of building in a new “Global Store” in the heart of London’s Mayfair, a wealthy neighborhood for the world if ever there was one. You don’t need to be an expert tea leaf decipherer to discern which markets this car is aimed at.

It bears mentioning that the Eletre’s focus on autonomy runs counter to the PR noises that Lotus is “For the Drivers”. There was a real opportunity here to do something truly different. Instead we have a car that, sustainability questions aside, has a confusing identity and no real connection to its forebears. That’s not totally surprising, as since the glory days of the wedge era Lotus has existed hand-to-mouth on countless Elise, Exige, and Evora variants. Now, owner Geely is signing the big checks, and it expects a return.

The problem with this newest Lotus isn’t just the mixed messaging, it’s in the inoffensive appearance. The side views in the press shots are all flat orthographic images—always a bad idea because the human eye never sees a car that way. The black cladding trick I’ve written about before hides some of the bodyside, but combined with the bright yellow it exaggerates the length (especially in the overhangs). Look at the width of the C-pillar behind the glazing. It’s huge. Lotus has tried to hide it by slightly raising the color split, but that adds visual weight to the rest of the bodywork, making the whole area above and behind the rear wheels look heavy and saggy. Making the split line flatter and in line with the base of the side windows would possibly have worked better. At the leading shut line on the bodyside, you’ve got four surfaces on the fender meeting six surfaces on the driver’s door, and the charge port. It’s all very unresolved and untidy.

The rear light graphic is simplistic, flat, and could do with some shape to add tension, break up the surfaces, and give it more of a distinct identity. How many other Future Cars will use straight lines for their rear lighting? I see it in student sketches all the time. Viewing the front, there’s a hint of supercar wedge in the leading edge of the hood, but it’s minimal visual lip service. At the base of the nose are the hexagonal active cooling vents; it’s difficult to integrate such rigidly geometric shapes, so designers have hidden this feature that they’re making a big fuss about in the black graphic along with the main beam units. The whole thing feels like what the actual concept of the car is—a fashionable line of least resistance.

The best Lotus designs had a sense of drama, exoticism, and well, British underdog uniqueness about them. After Giugiaro penned the Esprit, British designer Oliver Winterbottom took his sharp-edged ideas forwards with the four seater Eclat, Elite, and Excel. Supercar gun-for-hire Peter Stevens (of McLaren F1 fame) successfully massaged the straight lines off the original Esprit for the Nineties without altering its distinct look. When Julian Thompson drew the Elise, he brilliantly hid its parts bin parsimony and made the underlying engineering part of the design.

To be clear, I’m not anti-SUV at all. My daily driver is now a 2011 Range Rover Sport and I love it. I know where its talents lie, and moniker aside, where they don’t. Daily errands are performed in complete comfort, Meridian stereo booming with industrial music. It’s brilliant. I don’t need thrills going to the supermarket, I need the groceries to not get smashed into the world’s worst soup in the trunk. When I want thrills, I have something redder and more Italian. The best SUVs have never tried to be something they are not. GMT400 Suburbans make my heart sing with their assertive modern simplicity, and the current Navigator is a handsome compelling domestic take on regal luxury. The hot-off-the-press L461 Range Rover Sport looks muscular, modern, dynamic, and dare I say it, sporting.

At the time of his demise, Chapman was looking to expand the Lotus range. Although he had Range Rover as his personal vehicle, they were a left field option in 1982. He was thinking more of a four-door super saloon, the Eminence. He commissioned Italian industrial designer Paolo Martin to come up with some sketches and a quarter-scale model. It failed to progress further because of his death. So when Lotus designers tell you he would have approved of the Eletre because it was a practical four seater “for the drivers”, don’t believe them. If Chapman would have approved it, the only reason would be because it’s going to make lots of money.