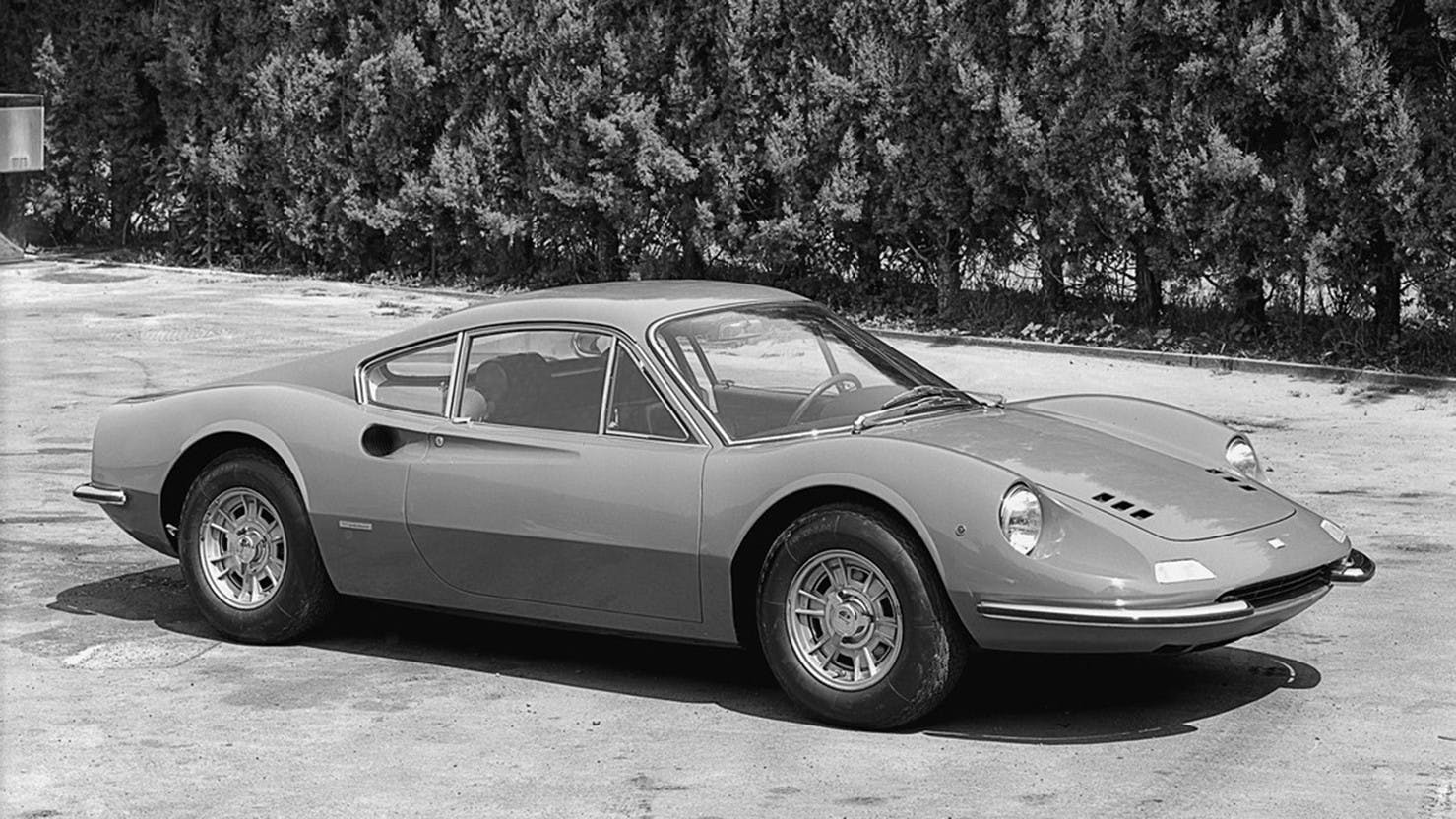

Your handy 1969–74 Dino 246 GT and GTS buyer’s guide

It seems insane now, when a Dino 246 GTS would run you about what a decent house in Portland, Maine would cost, but at the time the Dino 246 GT was introduced, some didn’t consider it “real Ferrari.” And that’s despite the fact that the 1970 brochure called it “proof of the constant development of smaller Ferrari cars.”

It had been a rocky start. The low-production 206 from whence the Dino 246 sprang had anything but an easy launch. “I watched Italian owners suffering the pangs of growth with the early models,” wrote Denis Jenkinson in the September 1971 issue of Motor Sport, “in the days when it was the thing to do to sidle up to the owner of a Dino Ferrari as he was about to drink his coffee and innocently enquire ‘How’s the Dino?’ Nine times out of ten he would spill his coffee as he hastily snapped ‘Why?’ Early Dino owners were very touchy about the fact that they had paid an awful lot of money for a car that was still having teething troubles.”

But with each passing year, the 246 GT and later 246 GTS earned their reputations as fabulous automobiles. Start with the superlatives. The 206, produced in just 152 examples, was the very first mid-engine Ferrari road car, laying the groundwork for most of the iconic Ferraris to come afterward: The 512BB, the Testarossa, the Enzo, and the current F8 and SF90 Stradale. It was the first Ferrari to feature a transverse-mounted engine. It was the first road-going Ferrari to run the Dino V-6 conceived by and named for Enzo Ferrari’s son, and it was also the very first street Ferrari with an electronic ignition.

Leading up to the production version of the 206 GT, Ferrari showed five prototypes: The Dino Speciale Berlinetta at the 1965 Paris Auto Show, the Dino Berlinetta GT at the 1966 Frankfurt Auto Show, the Dino Berlinetta Prototipo Competizione Pininfarina at the 1967 Frankfurt Auto Show, and the earliest known production 206 GT at the Brussels Auto Show in 1968.

Whenever Denis Jenkinson was asked how the 246 GT drove, he responded with the question: “How does it look?” The only response was that it was gorgeous to the eyes. “That’s how it goes,” he’d always conclude. It’s not a difficult equation to understand.

1969—70 (L Series)

Penned by Aldo Brovarone and Leonardo Fioravanti at Pininfarina and brought to life as an aluminum monocoque by Scaglietti, the Dino 206 GT’s styling was unimpeachable. The Dino was the bridge between the soft-edged, curvaceous lines of 1950s and 1960s Ferraris and the origami style of every road-going Ferrari that would come after it.

The Dino 246 GT went into production in March of 1969. The biggest change wasn’t to the engine, it was to the monocoque. The silhouette looked the same, but the central structure was constructed of steel rather than aluminum to save money. Most, though possibly not all, L Series cars were equipped with aluminum doors, hoods, and engine covers. The vents in the engine cover differed slightly from those in the 206 GT’s: two rows of six, rather than two rows of seven. The 246 GT is two inches longer in wheelbase, and four inches longer overall. The 246 GT was also an inch taller.

The suspension was relatively conventional: fully independent with upper and lower control arms and coil springs at all four corners, with slender antiroll bars front and rear. The brakes are all outboard discs with single-pot calipers. Steering is provided by an unassisted rack and pinion setup. Wheels were center-bolt style Cromodoras with knockoff hubs.

The trouble with the 206—and the reason for the 246 GT—was the engine. Ferrari’s idea was that the engines would be purpose-built in Maranello, but Fiat management insisted on producing the engines on the Fiat line. Whether you bought a Dino 206 or the Fiat Dino, you got the same engine, produced by the same Fiat workers.

The Dino 246 needed more power, and it needed an exclusive engine if it were to have any hope of success. Within a year, Ferrari developed its own 2.4-liter, 65-degree dual-overhead-cam V-6 with triple Webers and a cast-iron block. In European form, the engine turned out 195 hp, but those cars bound for the United States had timing changes and an air pump that dropped power to 175 hp.

The 65-degree vee is wholly unique to the Dino’s engine. The banks of most V-6 engines are arranged in a 60-degree vee, but Dino’s extra five degrees allowed for straight intake runners. The crank also has separate crankpins for every piston, which allows for even time between firing pulses. (V-6s at the time were either odd-fire, like Buick’s 225, or had internal balance shafts to compensate for the uneven firing interval.)

Inside, the Dino 246 GT was typical Ferrari: well-sculpted dash padded and upholstered in suede-esque mousehair, heat controls in the center stack (over an opening in which a dealer would stick a Becker or Grundig radio), a straightforward binnacle containing the instruments, a non-adjustable steering column canted at an angle, leather bucket seats with headrests, and a console with a gated five-speed manual transmission gearshift.

When Denis Jenkinson drove his tester, he complained about exactly two things: The speedometer and tach were of equal size, rendering them indistinguishable in a single glance. (He’d have been happier with a Porsche 911-style arrangement, with a large tach front-and-center.) Second, the seat back was non-adjustable; but this grievance suggests he was driving a later-series car. These early L Series cars had tilt adjustment for the seat back.

Ferrari built 357 L Series cars between 1969 and the summer of 1970, all of which were left-hand drive. The first L Series car carries s/n 00400, and the last L Series Car was s/n 01116.

1970–71 (M Series)

While they look identical, there are a number of minor changes that identify the M Series cars. The wheels are the big revision. Rather than the knockoff Cromodoras, which were exactly the same as those on the 206 GT, the Series II cars featured five-lug, 6.5-inch-wide Cromodoras. The brake supplier for the M Series cars changed from Girling to ATE.

Outside, the lockable trunk button on the early cars disappeared in favor of an interior latch. Exterior door locks moved from the scoop area to a position lower on the door. Earlier cars had twin reverse lights mounted under the bumper, but the M Series only has one. All M Series cars had aluminum doors, but the hood was often made of steel, for reasons unknown.

On the interior, the M Series had courtesy lights which activated when the doors were opened. The footwell on the passenger side became shallower, and the folding footrest in the L Series cars disappeared. Each of the doors was equipped with a small storage box.

In October of 1970, Ferrari produced right-hand-drive Dinos, according to the Dino Register. Beginning with s/n 01250 there was a minor mid-year change to the front bumper. M Series cars begin with s/n 01118 and end with s/n 02130 in 1971. Ferrari built 507 M Series Dinos in total.

1971–74 (E Series)

Beginning with s/n 02132, Ferrari kicked off the E Series, with another host of minor changes. Even so, it’s confusing to distinguish them from earlier cars. For example, all L and M series cars used “clapping hands” wipers that parked in the center of the cowl. Early E Series continued with those wipers but, beginning in 1972, the wipers both swung in the same direction and, when not in use, rested toward the left side of the windscreen.

Here’s the kicker: That’s not a hard-and-fast rule. For example, cars bound for the U.S. may have continued using the earlier wiper system as late as s/n 05100, and the few right-hand-drive cars Ferrari built would continue using the earlier center-park wipers throughout the production run. E Series cars also had steel doors in most cases, though the hood often was constructed of aluminum—but not always.

Beginning with s/n 03408 in 1972, Ferrari began offering the 246 GTS, introducing a targa roof for the first time. The 246 GTS was only offered from 1972 to 1974. According to the Dino Register, beginning with serial numbers “in the 4000s,” Ferrari began offering the Dino 246 GT with 7.5×14 Campagnolo “Elektron” wheels and a fender flare option. The option added $680 to the price of a standard Dino.

The Dino Register also suggests that the owner of Dino 04878 claimed to “have a letter from the Ferrari factory which states that his car was the first to be equipped with Daytona seats by the factory.” The seats and wider wheels were often ordered together, a pattern which lead to the Dino “chairs and flares” moniker, but the seats and wheel flares were two separate options.

The E Series is by far the most plentiful Dino 246, with 2897 built in total. Of those, 1623 were 246 GT coupes and 1274 246 GTS models featured the targa roof.

Beyond the series changes, it’s also important to understand the differences between cars built for Europe, England, and the United States.

European cars: The home-market versions of the 246 GT and GTS were identified by their turn signal lamps, which were flush with the bodywork. Most of the time, these lenses were clear. The European cars also had redundant turn signals—which were small, round, and amber—mounted on the sides of the front fenders. Chassis numbers were stamped on a tag on the windshield pillar, but it’s important to note that these are often missing.

British cars: Cars bound for England were right-hand drive, but they also had amber turn-signal lenses, as opposed to the clear lenses usually found on the home-market cars. After s/n 04830, the chassis numbers moved from the aforementioned tag to a stamping directly on the steering column.

U.S.A. cars: American cars had yet a third style of front turn signal. They were amber and recessed into the bodywork, and the lens stood up vertically from the body, as opposed to the flush mounting of those on European and British cars. Cars bound for the U.S. also had rectangular marker lights at all four corners, as well as reflectors mounted on either side of the number plate. All U.S.-bound cars featured the appropriate emissions controls, as well as a serial number stamped on the steering column and visible through the windshield.

Before you buy

A steel monocoque equals major rust concerns. This isn’t a Jeep CJ5, where you can jack up the body and order another one online. Rust in a rough Dino will consume more dollars than the initial purchase. Corrosion in the center chassis tube is lethal. Corrosion in the lower doors, steel or aluminum, is common, and in the wheel arches, too. The sandwiched steel panels behind the rear wheels will also trap water and rust.

Mechanically, cooling issues were especially problematic for the Dino. The car should run in the 195-degree range. Climbing up to 225 indicates an issue. Electrical gremlins can keep the cooling fans from running, and the electric motors themselves can die over time. Air can get trapped in the Dino’s long coolant hoses and water pump inlet, and some owners report having to rebuild the water pump every 30,000 miles with new seals and bearings.

The Dino engine is reportedly about as stout as you can expect from a 50-year-old Italian sports car. The cams spin via twin timing chains and, to quote one expert, “I have never seen a V-6 [Dino] chain fail catastrophically.” When it comes to the gearbox, if a test drive reveals in any grinding between first and second, the synchro is shot and a gearbox rebuild is in your future.

These were the first Ferraris with electronic ignition. Magneti Marelli’s Dinoplex was one of the first capacitive discharge ignition systems on the market, initially developed for Scuderia Ferrari and quickly adapted for the high-revving Dino V-6, hence the name. When the key is turned to the on position, the transformer core will vibrate and emit a distinctive humming. If that’s not happening, you can often trace the problem to a failed power transistor. Beyond that, Dinoplex.org has everything you could possibly want to learn about it, including an extensive diagnostic and repair document.

Electrics are not a Dino strong point. Experts suggest flipping yourself upside down and getting a look at the wiring behind the ignition switch. Any scorching will indicate significant wiring problems. Keep in mind that these cars are at best 47 years old and the wiring insulation is bound to be dried out.

The suspension is relatively standard and fairly easy to diagnose. Bushings and shocks go bad, naturally. Any twitchiness in the steering can be related to alignment issues. The brakes are about as straightforward as they get, and have no unusual issues. Steering racks are available from European suppliers, and run around $850.

Inside, age will have its way with a Dino’s upholstery and interior parts, but pretty much all the soft parts are available through suppliers like Re-Originals.

Valuation

Dino values took a dramatic hit during the 2008/2009 recession, but they’ve taken off since. Between 2009 and 2015, for example, a 246 GT in #2 (Excellent) condition climbed, on average, 206 percent. Values have tapered off a bit since 2017, falling about 17 percent, but the Dino enjoys a pretty stable market today. Cars from 1974 seem to appreciate a few percentage points faster than those from other years, but not dramatically so. According to the Hagerty Valuation Tool, a 246 GTS will cost $50,000 more than the coupe, but please check here for the most up-to-date pricing information.

Dinos are most popular among Baby boomers, who account for 62 percent of Dino quotes though they comprise only 37 of the collector car market. Gen Xers come in second, with 18 percent of quotes, and Preboomers third, with 13 percent. Millennial interest is the weakest: This set accounts for a bare 7 percent of Dino quotes, though millennials make up 19 percent of the market.

In 1985, Road & Track’s Peter Egan drove a 246 GT through a blizzard from Wisconsin to California. He said it was “the only Ferrari I desired that ever appeared on the used car market at prices a man could nearly afford if he sold every last thing he owned, except for his old British sports cars.” Thirty-five years later, that’s still true. Ditch your house, your motorcycles, and your guitar collection, and you might still be able to scrape together the funds to buy one of these gorgeous automobiles.