Why GM’s V-12 “Engine of the Future” never made it to production

Sixty years ago, General Motors was nothing like the company you know and (maybe) love today. In the 1960s, the firm was well-stocked with the industry’s smartest designers, engineers, sales experts, and division managers. No technical hurdle was too high, no engineering feat too far-fetched, for the colossus that bestrode more than 50 percent of the market and had no Asian competitors to fear. So when someone raised a hand and suggested that a nice, fresh V-12 engine would add luster to Cadillac’s prestige, there was broad consensus and no fiscal concern.

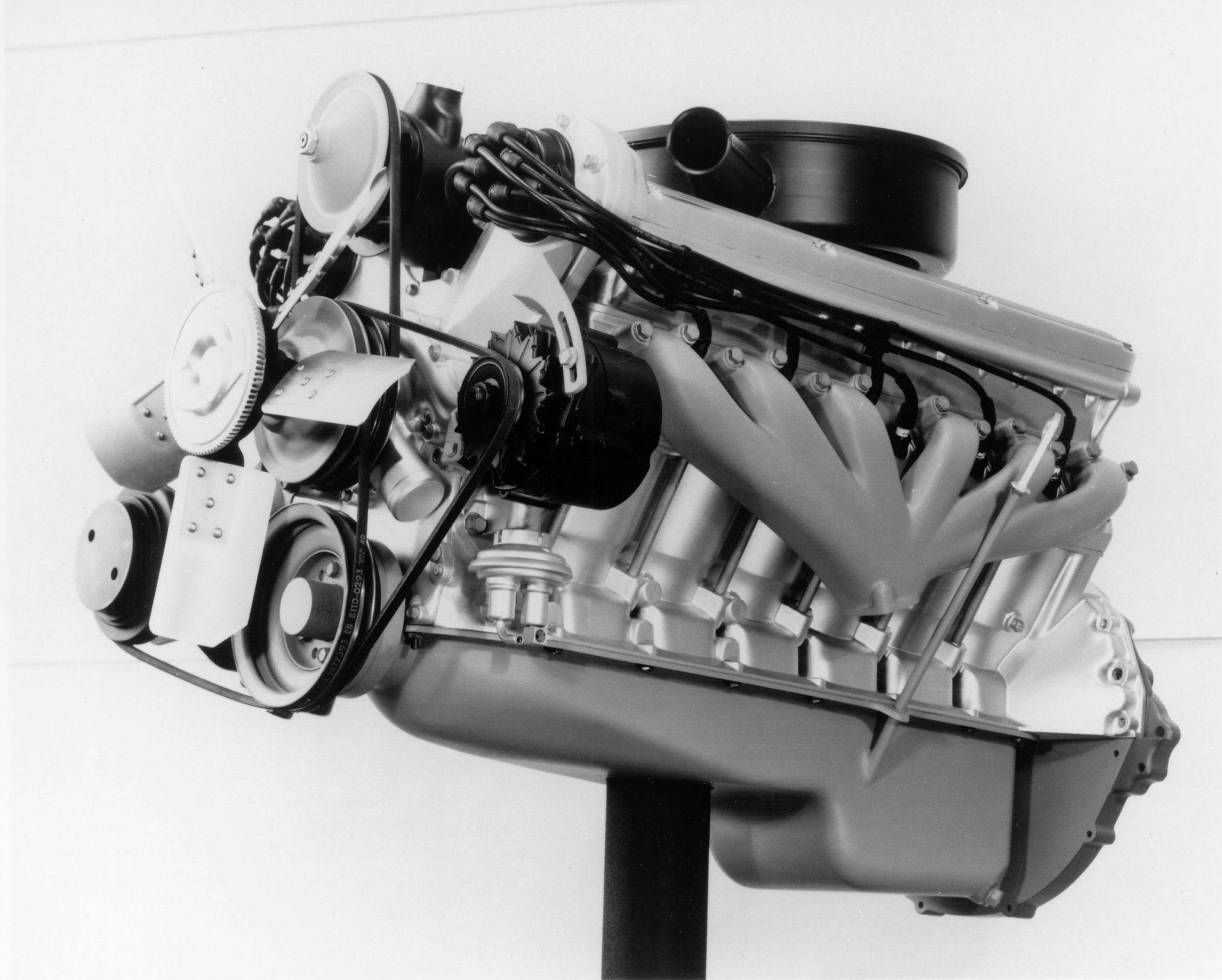

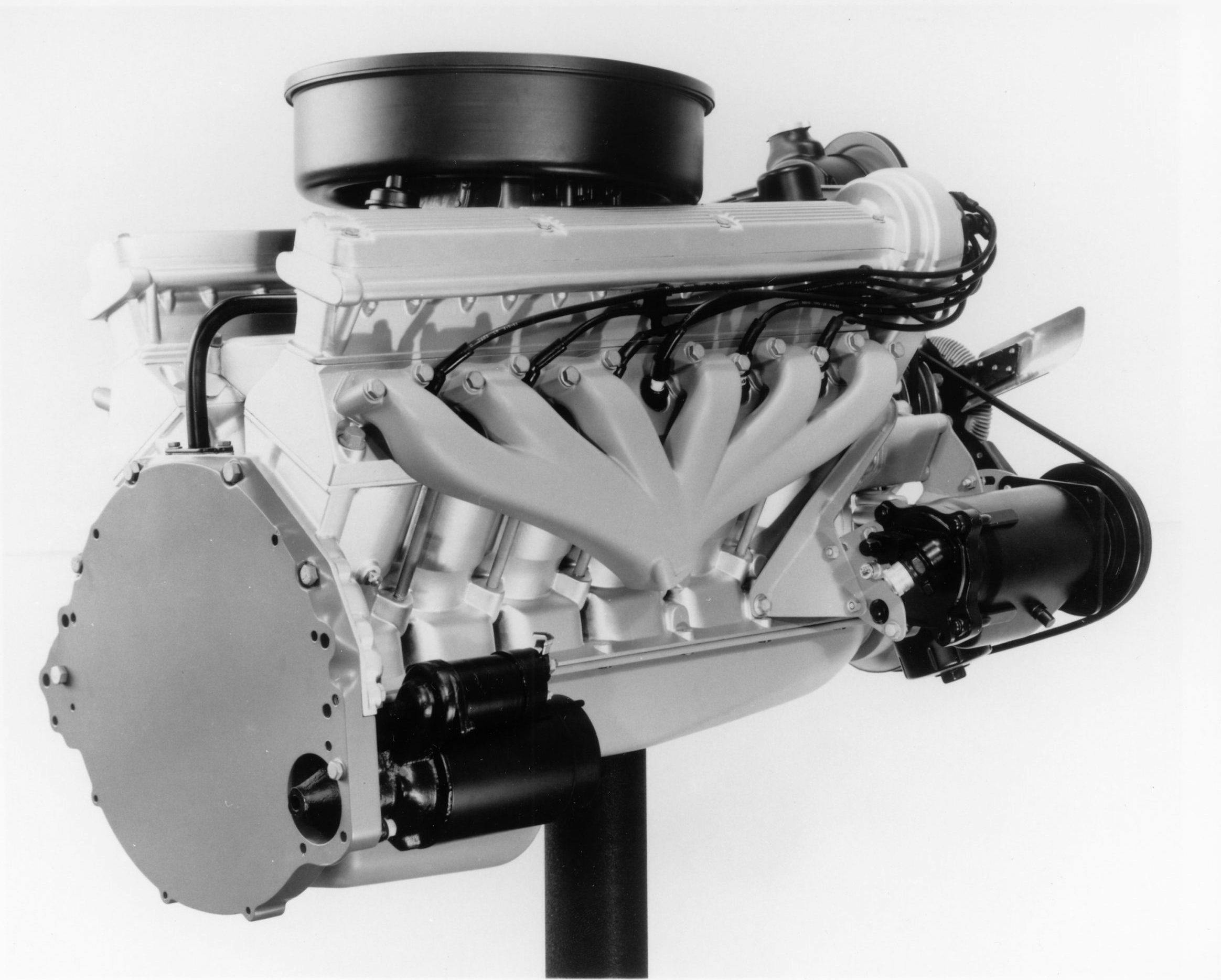

Indeed, there was plenty of precedent for the idea, both historic and recent. From 1931 to 1937, Cadillac built and sold just over 10,000 Series 370 and Series 80/85 models powered by V-12s serving as the base engine. (The upgrade was a V-16 offered from 1930–40.) In 1960, GMC introduced a 702-cubic-inch “twin-six” truck engine consisting of a 60-degree V-12 block topped by four V-6 cylinder heads. (See what we mean by “no fear”?) Around that time, engineer Paul Keydel was assigned the task of designing GM’s ambitiously-named “V Future” program—a fresh V-12 for Cadillac’s exclusive use. He picked a 60-degree layout with a single chain-driven, overhead camshaft per bank. A horizontal distributor poking out of each cam carrier fired six spark plugs. The block and heads were both aluminum castings. To make the blocks, GM invented a technique called Acurad, which injected high-silicon aluminum into steel dies at high pressure. The beauty of this arrangement was that it yielded bore surfaces tough enough to resist piston wear and abrasion without ferrous-metal (iron or steel) cylinder liners.

Finger followers with hydraulic lash adjusters were fitted to the heads. Cadillac built six V-12 prototypes for testing and development, with displacements ranging from 7.4 to 8.2 liters. However, when the first engine fired on a test stand in 1963, results were deeply disappointing. Power and low-speed torque barely topped Cadillac’s existing 7.0-liter V-8. Switching to individual intake and exhaust pipes and adding fuel injection to optimize fuel-air distribution eventually raised output to 394 hp and 506 lb-ft of torque, beating the V-8 by roughly 100 hp. Unfortunately, engineers then sacrificed half the V-12’s advantage over the V-8 by adding Cadillac-quiet mufflers, though they continued experimenting with various cam profiles and single 4-barrel, 2×2-barrel, 3×2-barrel, and 2×4-barrel carburetor setups.

At the same time, GM product planners expected the V Future engine to power the new Cadillac Eldorado coupe planned for the 1967 model year, which would arrive one year after the launch of the all-new Oldsmobile Toronado. Both were radical (for the era) front-wheel-drive cars, and the folks designing their automatic transaxles assumed the engines in each would be transversely mounted. Cadillac quickly raised both hands in protest, stating that there was no way its new V-12 would fit sideways.

This forced the engineers to create a new, three-speed Turbo-Hydramatic 425 design that shared parts with the existing Turbo-Hydramatic 400. Here, the torque converter bolted to the engine’s crankshaft as usual. Next came a multi-link Morse chain that dispatched torque to the left (in plan view) to drive the remaining transmission and differential components snuggled against the engine with a “backwards” north-south orientation. Torque to the left wheel departed the left side of the differential. Torque to the other side was via a driveshaft which went through the oil pan and under the crankshaft before reaching the right-front wheel. This design became known as the Unified Powerplant Package.

While the UPP design sounds like it was heavily influenced by Rube Goldberg, it worked reliably as intended. There was zero detectable torque steer; the only real drawback was that any engine mated to the 425 transaxle had to be mounted a bit higher in the chassis to provide driveshaft clearance beneath the crankshaft. Using the 455-cu-in Oldsmobile V-8, the UPP would go on to power that brand’s stylish new Toronado—and, when mounted under a pair of space-age seats, would also motivate the radical front-wheel-drive GMC Motorhome. (Later variants of the UPP would have a 403-cu-in V-8 in place of the 455.)

When the UPP appeared in the Eldorado, however, it was mated to an 8.2-liter V-8, not a V-12. What happened? Contemporary sources believe that GM was worried about releasing an engine which exceeded the V-8’s thirst by a considerable amount without having a similar power advantage. Expanding the Cadillac V-8 to 501 cubic inches closed the gap to the V-12 with significantly less investment. Given the GM design staff’s unshakable preference for long-hood, short-deck proportions, they weren’t about to protest an engine compartment that was only 2/3rds full. Ultimately, all that really mattered was sales volume. Even though it had no V-12 about which to crow, Cadillac easily doubled the sales of its arch rival Lincoln Continental 2-door hardtop coupe with its stunning new Eldorado during 1967 and ’68 model years. Shortly thereafter, federal emissions and mileage requirements gave the engine design department much more to worry about than cramming extra cylinders under Cadillac hoods.