When America reinvented a Ford to get stuff done

Across the digital world, most published content is bite-size, designed for quick consumption. Still, deeper stories have a place—to share the breadth of an experience, explore a corner of history, or ponder a question that truly engages the goopy mass between your ears. Pour your beverage of choice and join us each day this week for a Great Read. Want more? Have suggestions? Let us know what you think in the comments or by email: editor@hagerty.com

Forty-six and five-eighths.”

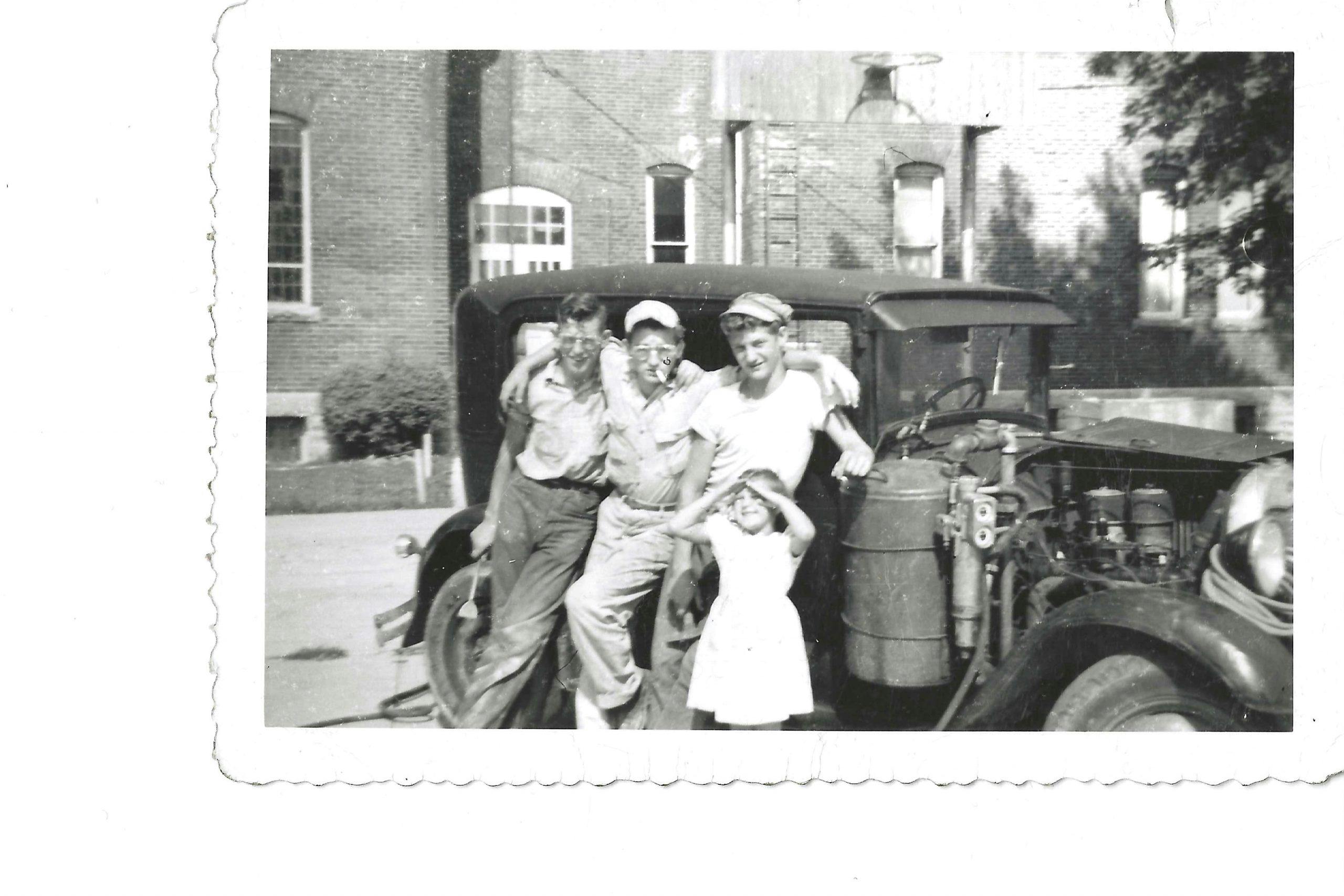

The tinny sound of a closing tape measure snicks out from under the green Model AA ambulance, a pair of New Balances poking out beneath the running boards. Ron Ehrenhofer cautiously extracts himself from under the rear axle, goal complete: He has measured the length of the rear leaf spring.

Katherine Brewer stands nearby, a bemused smile on her face, in a chic balayage bob and glittery sneakers. Brewer has been an engineer at Ford for 20 years. She got her start by designing intake manifolds but now manages three engine architectures. Ron’s rain jacket is draped over her arm. Katherine’s husband Todd, the technical advisor on top ends for virtually all new Ford engines, turns with a grin, twirling a finger by his temple. “This is what we do.”

It’s a drizzly Saturday morning at the Gilmore Car Museum, where the permanent collection ranges from Brass Era carriages to 1960s muscle. On a sunnier weekend, Katherine and Todd might be paddleboarding or skiing on the lake behind their house in southeast Michigan, or perhaps driving one of their Model A Fords to a coffee shop. Instead, they have taken a late-model Ford Escape 100 miles west to the town of Hickory Corners, population 139, to meet Ron Ehrenhofer and his brother Ken, who have themselves road-tripped in from Chicago.

They’re all here for the museum—more specifically, for a Ford that resides in it, a machine whose story has fascinated them for years and brought them into cahoots. It’s not the green bus. It’s not the 1930 Model A roadster parked in the corner, either, even though Ken and Ron say it is a dead ringer for the one they drove cross-country in the 1960s after graduating college, from Illinois to Yellowstone National Park to the old Shelby American headquarters in Los Angeles. Nor is it even the museum’s Model A pickup, which matches one that Todd bought in Texas and towed home.

They are together because, nearly 100 years ago, one man watched a train obliterate an air compressor stranded on a set of railroad tracks and thought, Shouldn’t those things have wheels?

***

Katherine Brewer manages the official newsletter of the Smith Model A Motor Compressor Club. She says no one really knows what inspired Kentucky’s Gordon Smith to build a mobile air compressor, or what exactly gave him the idea to repurpose a car engine as the compressor’s pump. A few things are clear: When the U.S. stock market crashed in September of 1929, much of the country was forced to tighten its belt and get creative. City governments, businesses, and federal alphabet agencies created as part of the New Deal needed to power jack hammers, mining drills, and water pumps, and they jumped at anything that facilitated that brute work. Finally, by 1930, nearly 2.5 million Ford Model As had been sold in America. They were cheap machines with proven reputations, in driveways and scrapyards in droves.

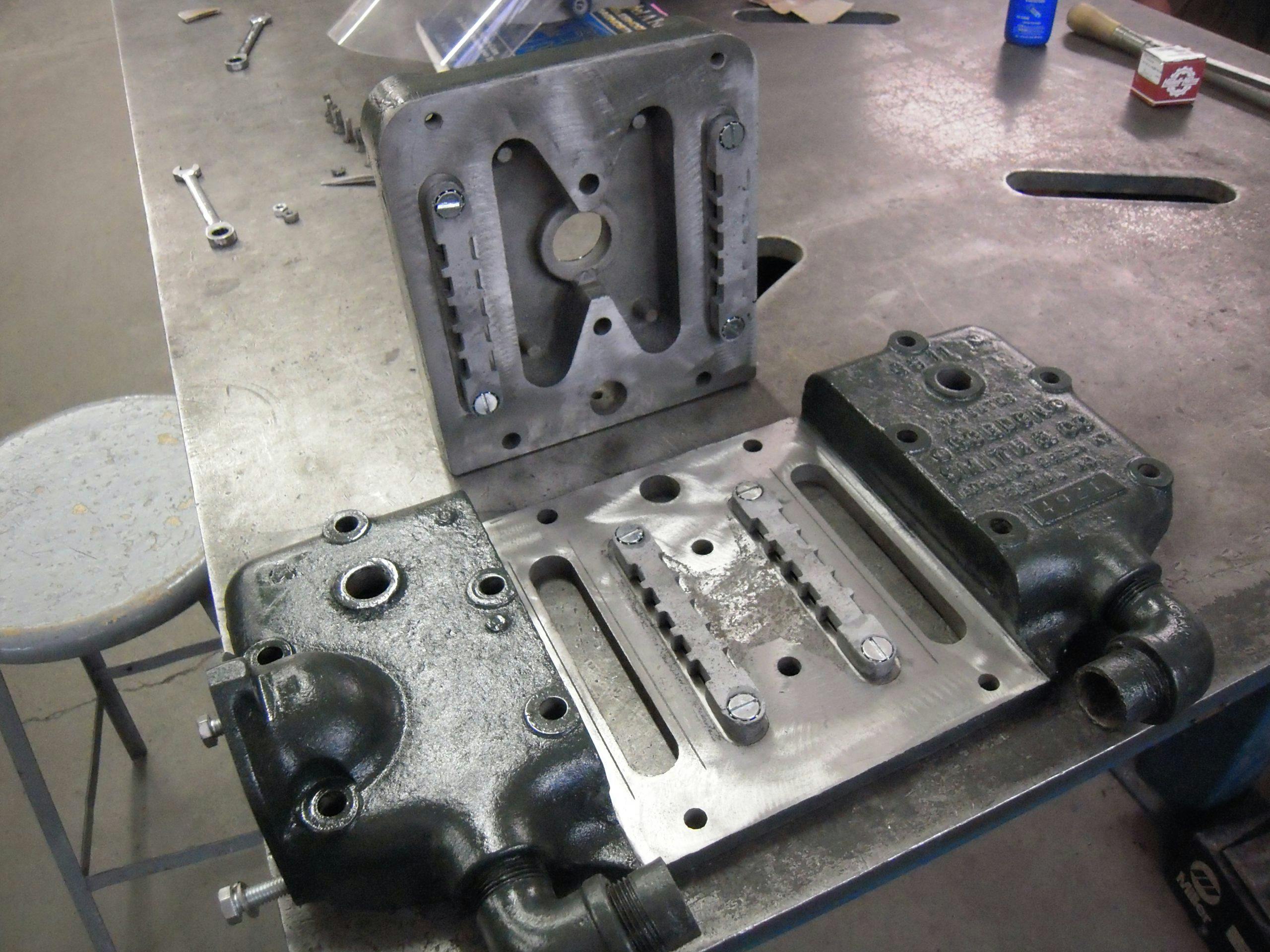

Building a wheeled air compressor from scratch would have been costly. Instead, Smith designed a clever system to retrofit a used Model A. On April 13, 1934, he applied to patent a cylinder head for the car’s 40-horse four-cylinder: Cylinders one and four burned gasoline, powering the engine as usual; two and three pumped air into a reservoir tank mounted in the pedal box.

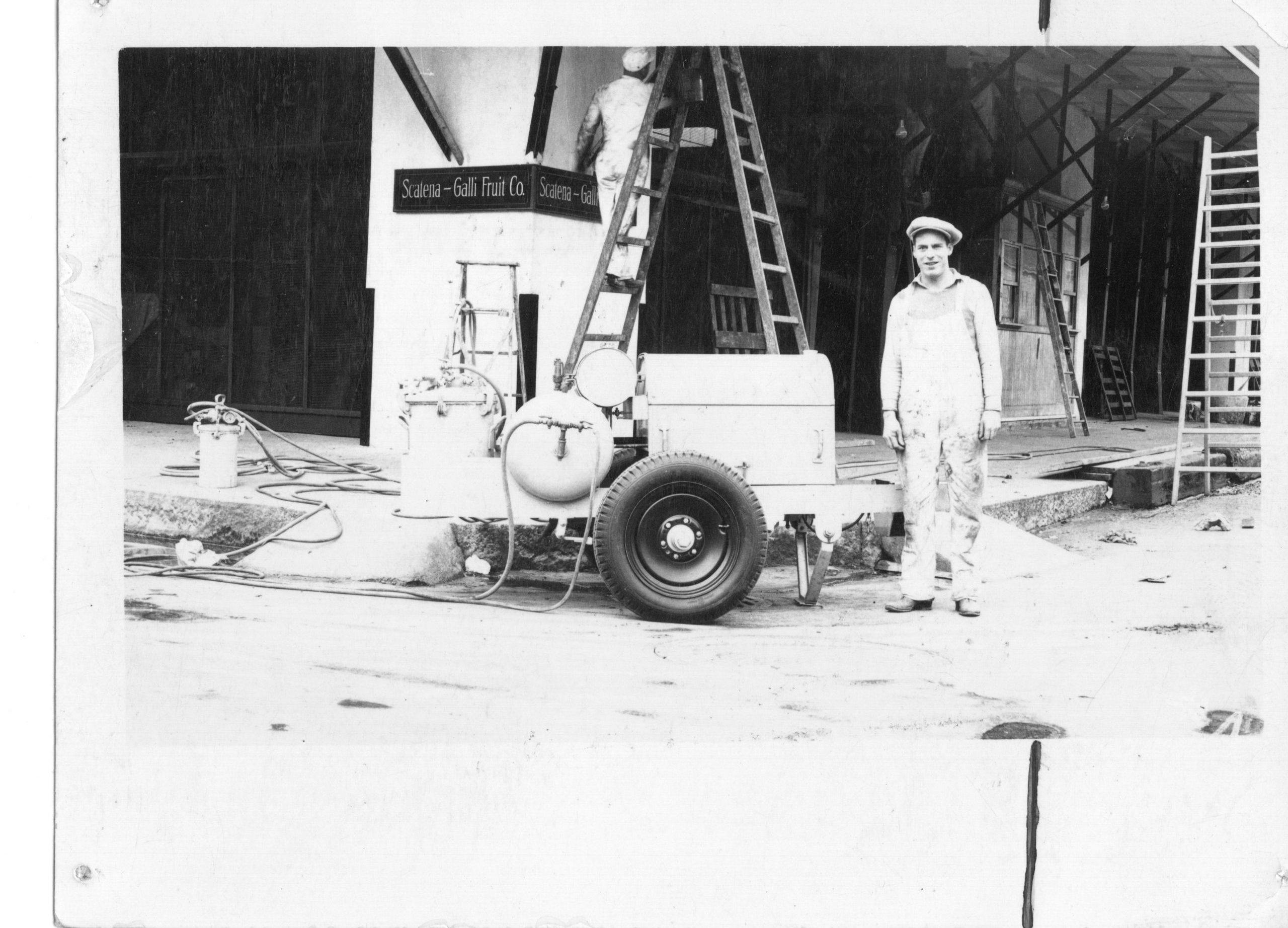

Contemporary newspapers record that Smith brainstormed this arrangement in connection with his day job at the Kentucky-Tennessee Power Company, but Mr. Smith was too savvy to let K-T take credit for his work. In 1934, from his shop in Bowling Green, Smith arranged a production contract with a foundry in Clarksville, Tennessee. Then he began peddling his cylinder heads across the country. Three months later, he had sold them in 18 states. On February 26, 1935, he won U.S. patent number 1,992,400. In 1937, Smith’s success was realized in brick and steel: a one-story factory in Bowling Green, on the northeast corner of College and Fourth. Three years later, he resigned from K-T to focus on his company full-time.

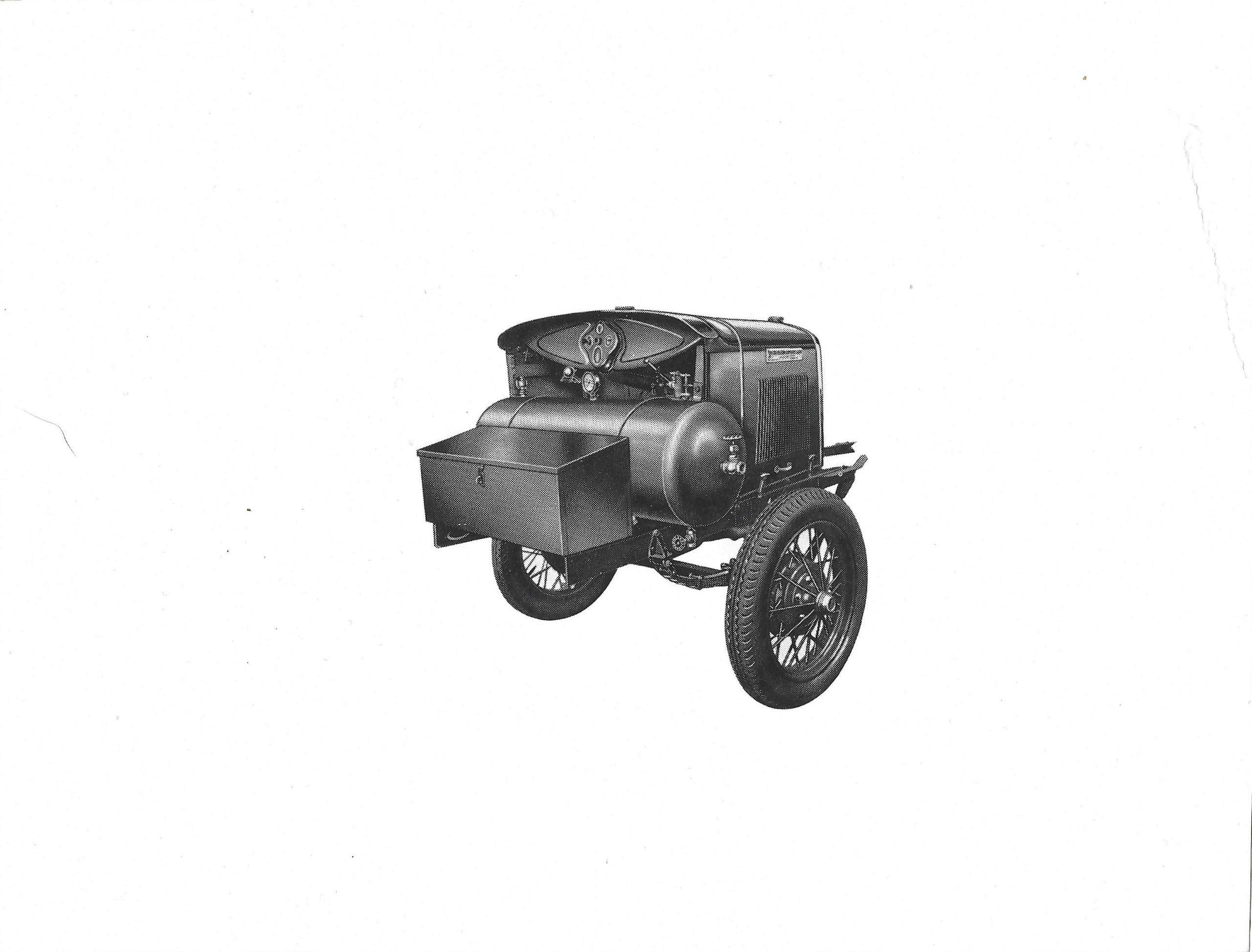

Smith’s conversions didn’t stop with a head swap. The rear two-thirds of a Model A were lopped off, sectioning the car at the cowl. Little of the vehicle’s front went to waste: The leaf springs that originally ran parallel to front and rear axles were removed, rotated 90 degrees, and remounted to support the two wheels of the now single-axle compressor housing. The original hood, radiator, grille, dash, and gauges remained. The Ford’s original frame rails extended forward from the radiator and remained to form a yoke for easy towing.

Even before he left K-T, Smith had attempted to go international. He partnered with England’s Johnson Machine Company to build what was branded as a Johnson-Smith compressor. The nation’s patent office took issue, however, accusing Smith of false marketing on the grounds that American patents weren’t honored overseas. Undiscouraged, Smith applied for at least four more patents, in Canada, Mexico, South Africa, and Argentina. It’s unclear whether any were awarded, but Smith’s customer base ranged far and wide: Canada’s Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company, in Montreal; a Robert Buron in Paris; a John Zehtner in Mexico; E. Boydell & Company in the English city of Manchester; a Gwyn E. Thomas in Haileyburry, Ontario.

The original production offering was a single-tank, 60-cubic-feet-per-minute affair designed around the 1928 and ’29 Model As, but the catalog soon expanded. The dual-tank, 120-CFM unit that came next, however, paled in comparison with customer builds. Smith encouraged people to engineer DIY compressors using his cylinder heads, resulting in some truly strange chimera: One man built a dual-engine cowl compressor looking for all the world like a double-headed Model A with no body. There were drophead cars with compressors in their trunks and radiators facing backward, stock-looking Model As with air tanks on the running boards, a Ford engine placed inside a giant rectangular body running on something like a carriage chassis.

These were strange children of necessity—but every one was also easily pulled, towed, and serviced by either you or your local Ford mechanic.

***

Inside a two-story, two-door garage in Belleville, Michigan, next to Todd Brewer’s pickup—the Model A he found in Texas—sits a rusty, spiderwebbed hunk of a red Ford on a wooden jig. In paint-splattered steel-toes and a hoodie, Katherine squats nearby, pointing out the machine’s water pump, distributor, carburetor, the equipment its compressor needs to function.

The minimalism and frugality of Smith’s engineering are inescapable in person. In addition to that stroke-of-genius cylinder head, his design required only 12 castings to convert an A’s engine from a producer of rotational energy to a compressor of gas. Each of his parts are embossed with the letters “GS” and a number from one to 11. A speed governor keeps the compressor from blowing itself up. Critical as well are custom suspension parts: mounts to accommodate the rotated leaf springs, plus a secondary wishbone setup, the legs of the wishbone bolted to the engine block and its base anchored to the chassis with a spring.

Katherine hands me a Smith head, bronze with patina and surprisingly heavy. It looks like something you’d break a toe on while exploring an old barn; the simplicity is a source of wonder and delight, she says, one she revisits whenever she walks into the garage or gets behind the wheel of an A.

“You can barely fix your own fridge any more without some kind of computer diagnostic system,” she laughs. “One of my favorite things about As and [Model] Ts is that I know from my gas pedal the direct linkage that takes me to the carburetor, right? And I know the direct linkage that takes my spark rod to the distributor, in terms of spark timing.

“We’ve taken it all apart—not in a ‘let’s take this apart and see how it works’ way, but because we’ve had to figure stuff out when it isn’t working properly. And there’s an empowerment to that, too, ’cause you feel like, well, whatever happens, I know I can fix it.”

Katherine designed the intake manifold for Ford’s 2.0-liter GDI engine from scratch. She doesn’t underestimate the Smith achievement.

“If you think about all the math and engineering [required] to make those two cylinders compress air, all the reed valves and strip valves to make sure [you’re only] taking air out of cylinders when they’re in the compression stroke … and also metering to make sure you don’t over-pressurize the cylinder, all the regulators and governors to keep the engine working at the right speed… it is amazing to think that, one hundred-plus years ago, with a pencil and paper and a slide rule, they were figuring this stuff out.

“When you think about the things we struggle to do today, with computers and CAE … In many ways, I think they were smarter, by not having those tools.”

Neither Smith nor Ford, however, cared much for novelty. Though Katherine describes her compressor project as a restoration, the boundaries of period-correct here are vague. To use up extra stock, the penny-pinching Henry Ford encouraged component overlap between model years—the earliest 1930 As, for example, wear 1929 instrument bezels. For Katherine, that approach is characteristic of the era. These days, she says, “we have this obsession with changing things.”

Even when Dearborn did change things, Katherine notes, the alterations were not revolutionary. Gordon Smith followed Ford evolution, adopting upgrades that dovetailed with his product. With the 1932 Model B, for example, Ford introduced updated carburetors and an enlarged intake. Since each of those parts bolts onto a Model A engine, Smith compressors often wear them. Other parts sharing was aimed at optimized cooling—all Smith heads used Model B water pumps, and enterprising compressor owners were known to use the larger radiators from Ford’s AA bus.

Next to the smorgasbord of prewar parts living on both floors of the Brewers’ garage, the modern 5.0-liter valve cover mounted between the two garage doors is an anachronism. “We’re not supposed to have that,” Todd admits; the two snuck it from Ford as memento of how they met. She was designing the intake manifold, he was designing the cylinder-head ports.

***

Webber has owned the same Model A for almost 59 years; the story began when he was just 23, recently married and in need of transportation to work. He picked up a Smith compressor as footnote to his Model A hobby, but he wasn’t hooked until he saw an advertisement for the club in a magazine. He sent in his $10 dues, telling fellow hobbyists that he lived not even a mile from Smith’s original factory. More important, he said, he knew employees who once staffed it.

Since beginning his own compressor restoration in 2014, Webber has unearthed a veritable gold mine of period photographs, advertisements, brochures, and repair manuals, even spoken with second- and third-generation Smith family. One of his most fulfilling achievements, though, was solving the mystery of an oddball compressor he picked up in 2014.

Webber had seen a lot of Smith units, but this one didn’t look right—it was not quite identical to factory units, and too well-built to be a homemade affair. Poring over old Smith ads, he stumbled upon a 50th-anniversary spread showing a compressor parked on the grounds of the Parthenon replica in Nashville, Tennessee. It was an exact match to the machine he now owned.

Curiosity became determination. After two years, Webber discovered that Gordon Smith had in 1933 authorized a Nashville-based company as his first distributor. Founded in 1929, John Peterson’s Peterson Auto Machine Company used conversion kits sold by Smith in order to convert a slightly different vintage of Model A—the 1930–31 model, not the factory-favored ’28 or ’29. Smith and John Peterson, Webber says, were like-minded, World War I-era machinists.

In a happy coincidence, the paint is flaking off the compressor in Katherine and Todd Brewer’s garage. Beneath the top layer of red, flashes of yellow are emerging—the machine’s original color, and the standard shade for every compressor the Peterson Machine Company built from Smith parts.

Brewer, Webber, and the Smith community believe only about a thousand Model As were converted by the Nashville firm. (“There’s no more than ten we’ve found,” Webber says.) Peterson only sold its compressors until about 1968, when Smith discontinued the conversion kits. “Holy grail” compressors are in the eye of the beholder, but the Peterson builds appeal to Webber for reasons beyond rarity—he just likes their story.

***

David G. Miller, Peekskill, New York: “At the present time we are using it to run two light pavement breakers removing ice from the Village streets.”

Werner Tank Company, Breckenridge, Texas: “We can use this machine for operating riveting and caulking hammers and air driven turbines for flue cleaning and have very satisfactory service, in fact, considerably beyond our expectations.”

Schmitt & Son., Inc., Milwaukee, Wisconsin: “We have had occasion to use the Smith Portable Compressor put out by your company. This compressor was used by us to run a Chicago Pneumatic Hammer on concrete breaking jobs.”

Gwyn Thomas, Ontario, Canada: “I have tested the machine on actual rock drilling and it works very well indeed.”

Franklin Davis, Georgia: “I am using the compressor for pumping water in a bathing pool. I run it about 20 hours a day. I change the oil in the motor every 36 hours and am using a good grade Pennsylvania SAE 40 oil. It is the best air compressor I have ever seen.”

***

By the end of World War II, Model A Fords had become scarce. Production had ceased in 1931, and the car’s longevity made it desirable even apart from the repurpose potential. The Smith company did everything it could to collect the remaining units: It bought new engines from Ford, advertised extensively requesting junked cars with redeemable engines, even sent employees to scout scrapyards.

The supply of Model A bodies and frames dwindled first. Gordon Smith and Company continued conversions while contracting body-panel production to a Nashville steel-stamping business. These “sheet metal” compressors mimicked the previous “cowl” compressors. When Smith’s stock of Model A engines ran dry, in 1953, the company looked around. Industrial inline-sixes from Chrysler were used first, followed by everything from Ford 302s to Wisconsin V-4s and John Deere diesels.

This was still a family business. Webber says that Smith’s older son, Tommy, was a stock-car racer trained in engineering at Georgia Tech. “He was a rising star in the company, and he died at age 29—but not before he got the new plant built, the one that’s right up the hill from me, in 1960.”

Smith himself passed away in 1963. Leadership passed to Tommy’s younger brother, Gilbert, but from there until the company shuttered, in 1993, we don’t know much.

***

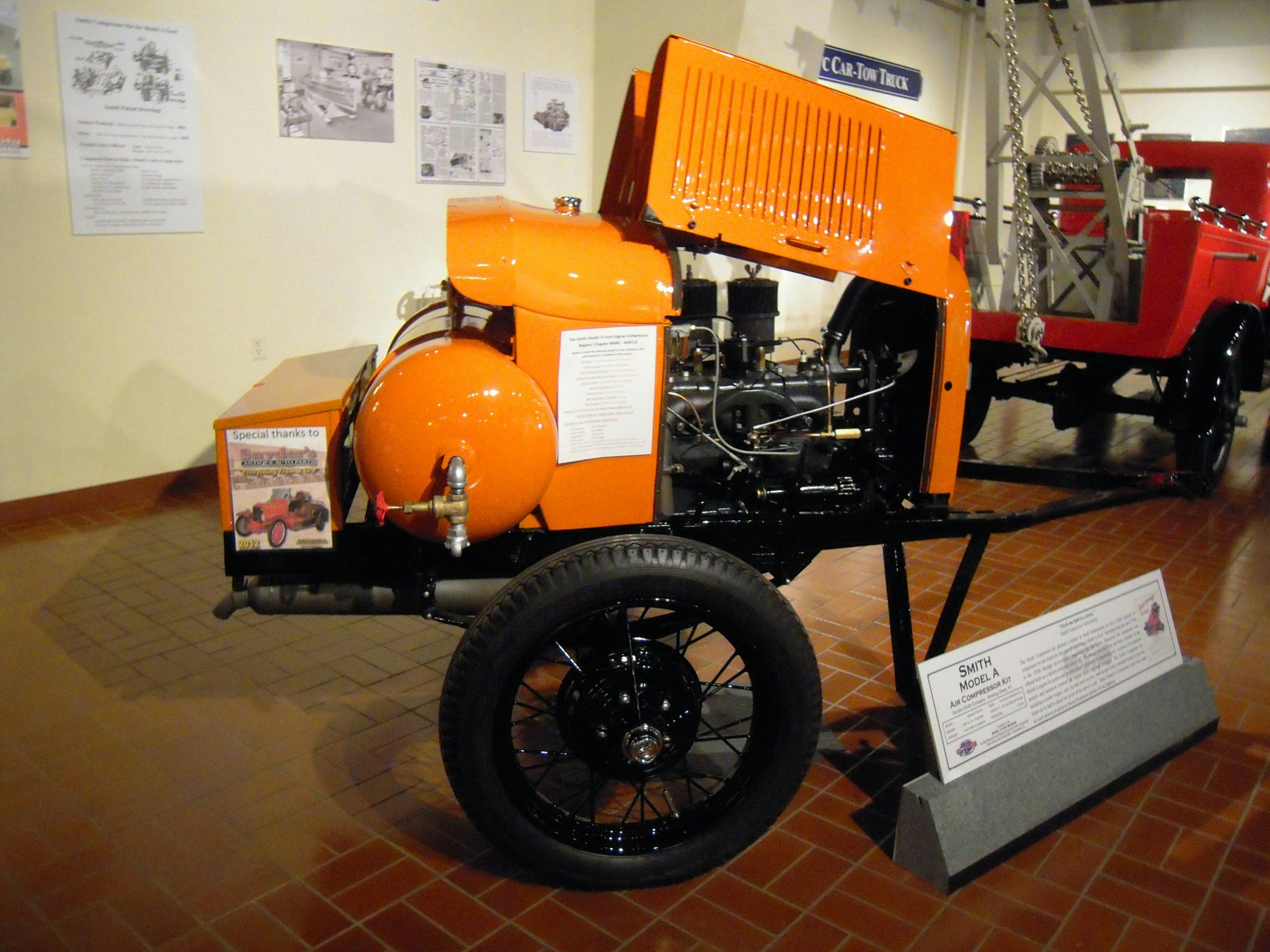

As we stroll toward the back of the Gilmore’s Ford building, past mannequins in period garb, the group lingers around a flawless orange Smith. This one was lovingly restored by Ken, with the support of the Model A Ford Foundation, then donated for display. Ford also owns a Smith, but that machine is locked away and can only be seen after paying a fee, if you even know to ask. (The Ehrenhofers agree its custodian isn’t particularly nice, either.) The Motor Company obviously sees the interesting parts of its legacy elsewhere.

With a quiet bit of pride, Ken and Katherine point out the extended frame, the air tank, the nozzle for attaching tools. Ken lifts the hood. The Gilmore’s halls have signs asking that you not touch exhibits, but the chatty museum guard in a corner of the room says nothing.

The exam is derailed by talk of lunch. The group ambles outside, through the rain, to the museum’s 1940s-themed Blue Moon Diner. With its chrome stools and pies under glass, the restaurant feels like a jolt forward in time. Katherine orders a Chicago dog, Todd a barbeque sandwich, Ron egg salad. Ron tells a story about growing up north of Chicago, where he earned pocket money fixing bicycles—“the rich kid’s Schwinn,” he says. He wanted a Model T ever since spotting one in a field on his eighth-grade paper route.

Katherine and Todd smile, teasing him for eating slowly. The waitress loops back around to pitch dessert. Outside the diner’s wide, low windows, the grey sky seems to dissolve the assembled kitsch, the double-wide building newly cozy and small, as if welcoming someone home.

Want more stories from our Great Reads project? Click here.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

Great story and history lesson. Thanks.

Absolutely great story. Well written and well researched.