Stock Stories: 1948–1971 BSA Bantam

With custom-bike culture exploding in recent years, the history and importance of early two-wheeled machines are often overlooked. Stock Stories tells the tales of these motorcycles.

The end of World War II marked the beginning of a period of enormous automotive expansion, as well as the birth of a market hungry for cheap transport. This era boomed with demand for small-capacity motorcycles, and British firm BSA was one of many eager to enter the two-stroke arena. In the end, it was a German company that provided the necessary inspiration for one of BSA’s best-loved bikes, and at more than 250,000 examples built over more than two decades, one of the best-selling English motorcycles of all time: the Bantam.

DKW and the birth of the D1

DKW, one of the four rings in what is now Audi, was a master of the two-stroke. The automaker began developing two-strokes in the 1920s, and by 1939 it had the largest racing department in the world, with 150 staff members dedicated to motorsport activities alone. By the late 1930s, the DKW factory in Zschopauer was the largest motorcycle plant in the world, having built more than half a million bikes. One of the brand’s most successful models was the RT 125, a lightweight, 125-cc unit. For BSA, it would prove the key to breaking into the two-stroke market.

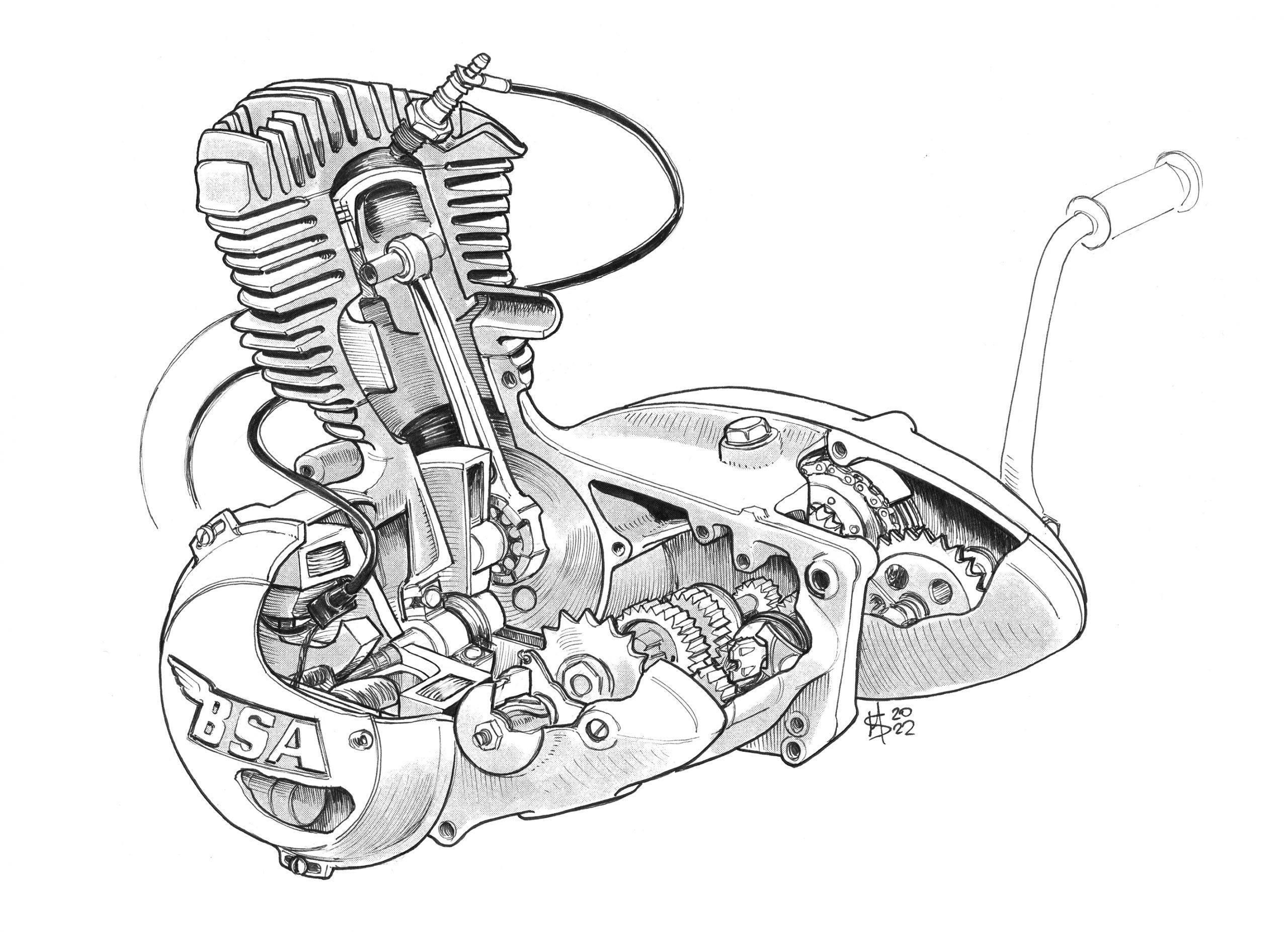

The RT 125 engine was designed by Herman Weber, with its defining elements being twin-loop transfer ports and a flat-top piston. Two-strokes were then plagued with the problem of unspent fuel-oil-air mix making its way into the engine’s exhaust—the result being both inefficiency and smoke. The twin transfer ports, one on each side of the cylinder, provided more chance for the incoming fuel-air charge to mix evenly while also helping spent gases escape. These ports also helped reduce weight, as their efficiency eliminated the need for heavy “deflector” pistons. The alternative, a flat-top piston, was significantly lighter.

BSA’s experimental department in Redditch obtained a complete DKW RT 125 in 1946. One story suggests that a wartime parachute regiment stole the motorcycle and delivered it to BSA, but there is no evidence that this actually happened. After stripping down the RT’s engine, BSA made its own drawings in Imperial measurements. Compared with British standard practice, the DKW’s drive sprocket and gear change were on opposite sides of the engine, so engineers chose to mirror the powerplant’s bottom half in drawings. The DKW’s rolling chassis was used to test BSA’s new engines; in the meantime, the British firm’s engineers got to work designing their own chassis.

BSA wasn’t the only one to take on Weber’s design. The DKW was the basis for many other machines, including the Harley-Davidson Hummer, the Royal Enfield Flying Flea, and Yamaha’s first production motorcycle, the YA-1.

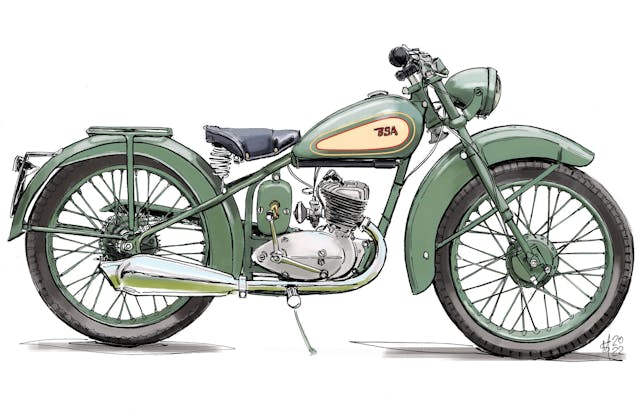

The Bantam D1 featured a fully welded, rigid rear frame and telescopic forks that used grease as a damping fluid. Electrical juice was provided by Wipac magneto, eliminating the need for a battery. That magneto also led to a simple push-bulb horn on the handlebars, a choice old-fashioned at the time but nonetheless adequate. With its substantial frame, its 19-inch wheels, a sprung saddle, and a small luggage rack on the back, the D1 was both capable and practical by the standards of the day.

In December of 1948, the U.K.’s General Post Office began using Bantams as cheap and economical transport for telegram service. The GPO put the D1s to hard work, running each bike over a five- to seven-year period with overhauls every 15,000 miles. Six thousand five hundred and seventy-four Bantams were purchased in a host of model variations, with the original D1 dominating GPO service; the model’s introduction coincided with peak usage of the telegram service.

The Bantam was also suited to motorsport, trials riding especially—it was affordable, lightweight, and highly tunable, with plenty of low-end torque. BSA saw the market potential, announcing the D1 Competition in 1949. This was a trials-focused model featuring an upswept exhaust, a decompressor, and weight-saving nonvalanced mudguards. The bike possessed all the essentials to tackle the trials courses of the day, an accessible package out of the box.

The Bantam began winning trials events virtually the moment they found riders’ hands. More off-road success came in 1950s scrambles events, most notably the Experts Grand National of 1956. Two Bantams ridden by Brian Stonebridge and John Draper were the last away from the line in that event but managed to make their way through the field and land first and second place, respectively—quite an achievement for a motorcycle initially designed simply to get you to work and back.

A similar story was happening in road racing as clubmen began to tap into the Bantam’s possibilities. An optional “plunger” version with rear suspension was soon offered alongside the Competition model—the sprung rear end was an improvement on the rigid frame, supplying more comfort than only a sprung seat. This feature was also used on the D1 De-Luxe, a Bantam variant that featured Lucas electrics. The latter change served as a mild improvement on the Wipac, but the setup was only used until 1953, when it was replaced by the Wipac Series 55 M8 generator.

Bantam D3 Major

It wasn’t long before customers began looking for more power in the Bantam’s cheap tax bracket. While BSA made attempts to create a whole new range of two-strokes, financial difficulties meant that the D1’s successor was only a slight evolution. Released in October 1953, the D3 Bantam Major was a 148-cc machine. The displacement allowed the bike to stay in the B1’s tax class but provided for a 16-percent increase in power: Output was now 5.2 hp at 5000 rpm. The D3’s rear utilized plunger suspension as standard, while the front end offered BSA’s C10 fork arrangement, a substantial upgrade over the D1’s layout. The D3 also introduced a range of colors; as of 1955, both black and maroon were offered alongside the green used on the D1.

The rigid and plunger frames were phased out in 1956, replaced with a new swing-arm frame, which gave more comfort and better handling. BSA also provided a dual seat and pillion footrests as standard. These improvements brought an increase in weight, however, which impeded the engine’s performance. The D3 was thus short lived, as it wasn’t quite enough to satisfy the customer.

Bantam D5 Super Bantam

By the mid-1950s, BSA was looking to compete against the popular Villiers 197-cc two-stroke, and so it began experiments to further increase the capacity of the Bantam engine. Early attempts involved trying a longer stroke to increase the displacement without changes to the bottom end. The long stroke gave strong torque, but it also produced strong vibration—so strong, in fact, that test engines rapidly destroyed their chain adjusters. Back at the drawing board, the design team decided instead to increase the engine’s bore size, a change that meant a redesign of the bottom end. The final result was a 174-cc, 7.5-hp single, a 44-percent power increase over the D3. Curb weight remained the same as the D3, and the added power gave a top speed of 60 mph. Riders could now cruise confidently at 55 mph while carrying a passenger.

Released in 1957, the D5 initially retained title of Major, but it wasn’t long before the bike was given the more marketable, more jet-age moniker of Super. As the majority of the model’s parts carried over from the D3—the engine was the main change—the D5 became the last of the first-generation Bantams, and in a way the last of the D1s.

Bantam D7

Going into what can be seen as the Bantam’s second generation, the D7 was the first Bantam to really suffer from neglect on the part of BSA. The company was at the time fully committed to the U.S. market. Unfortunately, the Bantam simply didn’t fit in a country of open roads and a public hoovering up big twins.

In retrospect, BSA should have invested in making the D7 a competitor for the likes of other small-bore U.S. stars like Vespa, Lambretta, Honda, and Suzuki. Each of those concerns produced user-friendly small capacity machines that didn’t require the rider to blend their own fuel-oil mix. By the time of the D7’s 1959 release, the overall cleanliness and practicality of the Italian and Japanese machines made the Bantam look like a messy, old-fashioned piece of kit.

The one thing that BSA hung on to was the credits of its engine: The Bantam’s low-end torque was desirable for urban riding, but it was let down by the gearbox’s aging wide-ratio gear stack. Hill-climbing was either a slow trundle or an ear-ache-inducing affair.

In an effort to solve this issue, BSA tested a four-speed D7 Bantam prototype, with TT rider Chris Vincent at the helm, but the motorcycle met an untimely end when it went under a large truck. Vincent survived but the bike didn’t, bringing an end to the four-speed’s development. The factory also tested a Bantam with a separate oiling system—no need for the rider to mix fuel and oil—and while that machine covered over 1000 miles in R&D, the project was eventually shelved and the money redirected to the development of bikes with larger displacement.

Although neither of these efforts saw the light of production, BSA’s styling department did make some changes in an effort to help the Bantam keep up with the competition: The engine was streamlined, a simpler dual seat design was introduced, and the instruments were incorporated into the bike’s headlight nacelle. Unfortunately, a mere clean-up in looks wasn’t enough to compete with marques that were pushing the boundaries of two-stroke design.

Despite all this, Bantams sold fairly well, mainly due to the model’s low price and tunable engine. The model wouldn’t see another revision for years, however, the D7 accumulating only small changes during its run. The factory simply saw no advantage in developing its smallest model while U.S. exports hit £1 million in 1964 and increased to £4 million by 1966. The only Bantam model specifically aimed at America, the Pastoral, was marketed as a farmer’s get-around bike; fewer than 600 were sold in three years of production.

D10 Bantam

Although the D10 Bantam was short-lived, it certainly changed how BSA’s lightweight was perceived. Replacing the D7 in July 1966, the D10 followed a similar development model to previous Bantams: power was increased, and yet the buying public was still expected to pre-mix their own fuel and oil, and to use hand signals instead of electric turn signals.

The D10 offered a higher compression ratio than its predecessor, at 8.65:1, and a larger, one-inch Amal carburetor. The result was a 40-percent increase in power, for 10 hp at 6000 rpm. While the model’s standard version still used the Bantam’s original three-speed gearbox layout, the long-awaited four-speed was offered on the D10 Sports and Bushman models. This was a dream come true for Bantam fans, especially the youth market, which had been customizing and tuning the model for years. The four-speed box made hills more of a pleasure, and it made the Bantam much more fun to ride.

Styled to follow period trends, the D10 Sports was clearly aimed at the popular cafe-racer market. This meant red paintwork, a cafe-style fly screen, a high-mounted exhaust, and a dual seat with a “racing hump.” Topping the styling off were exposed rear springs, chromed mudguards, and headlight and fuel tank capped with an iconic checkered stripe.

In another move that paralleled period trends, BSA developed a dedicated off-road model, the Bushman. While earlier racing-oriented models were aimed at the trials competitor—and the D7 Pastoral looked to American farmers—the Bushman was to marketed as a go-anywhere machine. Dreamed up by assistant export manager Peter Glover, the prototypes were built with a practical 10-inch ground clearance and a bash plate protecting the engine case. The rear suspension was uprated and so were the wheel spokes.

While the Bushman retained the D10’s alternator, the battery was thrown out and replaced with a Lucas energy transfer system. The dual seat was retained and further practicality was added with a substantial rear carrier. The striking orange-and-white color combination was chosen for its agricultural connections, a reference to tractor brands like Allis-Chalmers.

Although that last choice was controversial with some BSA directors, the colorway was well received by the marque’s 1960s audience. The Chalmers connection would have been clear to the American market, but it turned out that the real customer base was Australian sheep farmers, as well as Africa and the sugar plantations of Guyana, where it sold relatively well. More than 3500 Bushmans were built between 1967 and 1970, with the vast majority being exported to non-American countries.

D14/4 Bantam

It was only a year before the D10 was replaced by the four speed D14/4, putting the three-speed Bantam finally to rest. With its 12.6-hp output and 10:1 compression, the 14/4 was the most powerful Bantam yet. Top speed was a whopping 70 mph, at least on paper. Yet again the evolutionary loop happened with no sign of automatic oiling or turn signals—although powerful, the D14 remained stuck in the mud in modernity and practicality. The upside was a still-low price; at just £130 for respectable fuel economy and performance, the Bantam sold despite falling behind against the competition.

The extra power made the Bantam no longer a leisurely machine; with a 0-to-30-mph time of 4.1 seconds and 0-to-50-mph run six seconds quicker than the D10, it was, in period parlance, “a real goer.” The combination of high cylinder pressure and four speeds really brought out the best in the bike’s gearing, and the model was certainly a nimble and capable machine. Still, lack of investment took its toll, and the D14/4 wasn’t without its issues: newfound engine vibration caused driveline brackets to break; badly riveted compression discs would come loose; and the connecting rod’s small end would frequently fail. The model lasted just seven months.

During this time, BSA’s development department was working on the D18, a 100-cc prototype featuring a Minuki oil pump. The bike returned 10.5 hp and topped out at 82 mph in testing. This was real promise, but yet again, the powers that be were too caught up investing in new computerized production lines to press the green button on what could have been a real contender.

B175: The final incarnation

The final version of the Bantam was the B175, a motorcycle that looked very much like its predecessor. This time, however, BSA invested in a few improvements. One clear change was the new head design, which featured a centrally located spark plug, a mod Bantam tuners had embraced for 20 years. This simple change so late in the game demonstrates how much BSA neglected the Bantam for the model’s larger siblings. Despite this, the engine also saw various improvements, including a stiffened crankshaft with crankpins of larger diameter. A needle roller bearing was fitted to the clutch chainwheel, and the compression plates were no longer riveted, now held in by a rim lock. All signs that the D14/4’s issues had been taken seriously.

With the engine internals beefed up and Triumph Sports Cub forks fitted, BSA was clearly making an effort. Still, the changes were too little too late, and the lack of previous investment meant that BSA were still way behind the Japanese competition and struggling to keep up. After 20 years in production, and to the shock of the buying public, the model was dropped from production in 1971. This was the end of the humble BSA two-stroke, a machine that had become a real workhorse for both the public and the GPO. The latter kept their Bantams in service until the mid-1970s, having stockpiled a stash of B175s after the last batch was sold off in 1972.

The Bantam lives on today, especially in classic pre-1965 trials events, where the engine remains competitive. (Admittedly, it is often bolted into motorcycles so heavily modified as to not be very “Bantam.”) The engine’s durability and tunable nature remains, and the aspects competition riders found so agreeable in the 1950s are still tapped into today.

Outside of sporting activities, the Bantam has been for so many an introduction to the freedom and joy an affordable motorcycle can bring. I am certainly among those, and despite financial neglect in the model’s early years, it remains a fun and capable motorcycle.