Dig online into the history of your car—you might strike gold

While we’re all attempting to fastidiously avoid human contact, it seems like just the right moment to do some projects that have maybe loomed in the back of the mind waiting patiently for the free time that never seems to come. For me, one of those projects was hunting down some history on my 1949 Buick Special Model 46S Sedanet. Soon after I bought the car in 2007, I went down the ladder of ownership as far back as the 1950s the usual way, by getting the name and number of the owner previous to the one I bought it from, and from that guy getting the name of the one before him, and so on.

However, here in 2020, there is so much more information online that it seemed a good time to launch another research project into the car’s history. Carfax and other VIN-based vehicle history sites can help, but when your car is 71 years old, those sites can be short on leads.

It helps tremendously if you have a name. My old Buick came with an original owner’s manual into which was tucked the original Buick Owner Service Policy card. In neatly typed letters, it stated that the car’s purchaser, one Mrs. Odessa Hensley of Franklin, Indiana, bought 1949 Buick serial number 1502862 on December 4, 1948 from Woods & Vandivier Motor Sales at 101 E. Monroe Street, Franklin, Indiana. Here, I was lucky on a few counts: I had the name of the original owner, the original owner had an unusual name, and she lived in a small town. If your car was sold new to Robert Smith of Chicago, Illinois, your search may be a little more of the needle-in-haystack variety.

Back in 2007 when I first attempted to research Odessa Hensley online, all I was able to find was a Social Security record stating that an Odessa Hensley of Franklin, Indiana, had been born in 1890 and died in 1969. Nothing else was online about her and I figured that she, like so many people, had probably lived a normal life and died quietly, leaving behind little trace of her existence beyond a couple of footnotes in the Social Security record.

Boy, was I was wrong. Since 2007, so much more information has hit the internet, and last year I discovered Newspapers.com, which has become hands-down my favorite way to tap into history and to kill huge chunks of time in deep dives down historical rabbit holes. The site has scanned and uploaded tens of millions of pages of old newsprint going as far back as the 17th century. Back before media went digital and newspapers started dying off, the small-town paper was the daily record of life in America. Besides echoing the national headlines, they dutifully recorded the local politics, the births, graduations, sporting events, weddings, business openings, social gatherings, and deaths. Scanning old newspaper ads alone can eat an afternoon.

The site isn’t cheap; a six-month subscription goes for $75, though it does offer a seven-day free trial subscription, which is probably enough to get your research project done. But after that, consider throwing the site some money for the staff’s effort; maybe buy one six-month subscription. Then spend it reading The Indianapolis Star’s riveting account of the first Indy 500 in 1911, or The Detroit News’ breathless 1964 coverage of the launch of the new Mustang, or the Los Angeles Times reporting on the arrest of John Z. DeLorean as he was thumbing through a suitcase full of coke at an airport hotel, and on and on. I have researched everything from Lee Iacocca to 1950s fin cars to Subaru Brats on Newspapers.com and always, without fail, found fascinating information. Whatever car you own, it’s arrival almost certainly created news of some kind back in the day.

Once I put Odessa’s name in the search line, an unexpected trove of information uploaded to my screen. I learned that she was born Odessa Craft to George and Francina Roberts Craft on March 14, 1890 in Johnson County, Indiana, which is just south of Indianapolis. She went to school in nearby Hensley Township and married into the prominent Hensley family by wedding Richard Hensley, who died in 1931. Odessa worked in the State House in Indianapolis for 12 years as a filing clerk and, shortly after buying the Buick in 1948, ran as a Democrat for Franklin city clerk and treasurer on the J. Paul Kerlin ticket for mayor in 1951. The campaign spent $749 on the election, much of it on ads in The Franklin Evening Star, but lost to the Republican challenger by 57 votes out of 2903 counted on a particularly stormy day in November.

Odessa remained active in local Democratic politics as well as the Franklin Business and Professional Women’s Club, which met regularly at the Hopewell Presbyterian Church off Route 144 west of town. In 1958, she joined four other women in attending the National Democratic Campaign Conference in Washington, D.C. A photo shows them all together smiling in their print ’50s swing dresses and hats. In the fashion of the day, the women were listed by their husband’s names, as in: Mrs. Richard Sheek, Mrs. Hallard Ferguson, and Mrs. William D. Vandivier (which may explain why Odessa went to Woods & Vandivier Motor Sales for her Buick purchases).

As I learned from her obituary published on December 8, 1969 (almost exactly 20 years to the day after she bought the Buick, and two months after I was born), her busy civic life was tinged with personal tragedy. Two of her children, Mrs. Vivian Smith and Robert Hensley, both died before her. Her third child, Jewell Hensley, went to war and served in the 41th Tank Battalion, the Thunderbolts, of the 11th Armored Division, which fought in northwest Europe as part of Patton’s Third Army. The first time Jewell and the Thunderbolts saw combat was in the snowy forests of eastern Belgium on December 30th, 1944 as part of Third Army’s counteroffensive in the Battle of the Bulge. He survived the battle as well as the march into Germany, and returned home to Johnson County to become a farmer in nearby Trafalgar, Indiana. However, he died in 1995 apparently without ever having any children. And there the Hensley story seems to end.

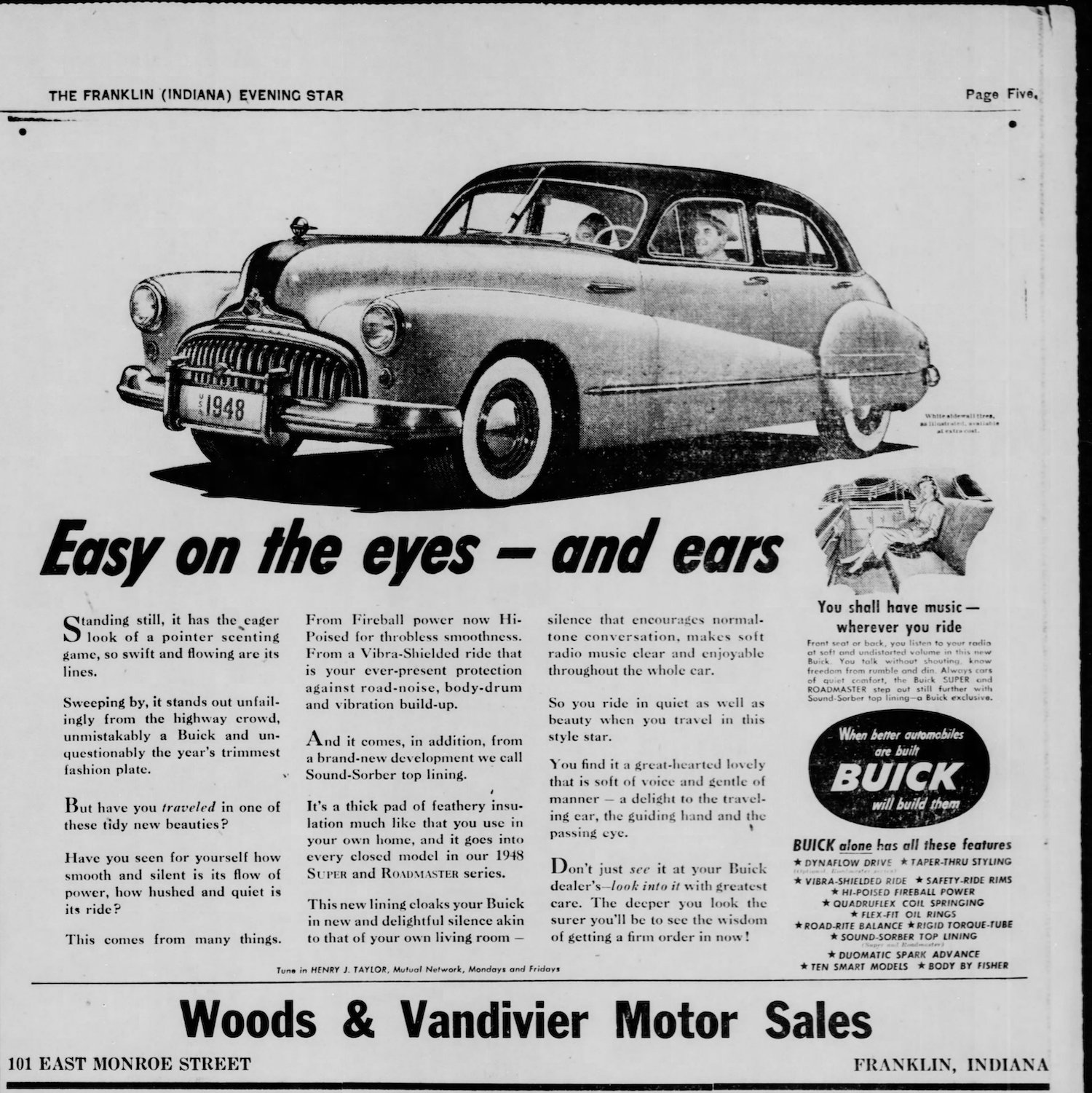

Back then, it was common practice for newspapers to publish people’s addresses after their names. Odessa’s trim little house at 469 N. Main in Franklin where she lived most of her life still stands, though what’s left of the dealership a half mile away is now a Zumba studio. Back in the day, Woods & Vandivier was a frequent advertiser in The Franklin Evening Star, touting everything from the new Dynaflow transmission—“For the first time, oil does everything!”—to replacement Fireball engines for your worn-out prewar Buick.

One of my favorite Woods & Vandivier ads is for Buick’s new Sound-Sorber headliner, one of the many hilarious marketing names Buick gave to otherwise ordinary car components. “BUICK alone has all these features,” shouted the ad, listing such modern marvels as the Vibra-Shielded Ride, Quadruflex Coil Springs, Flex-Fit Oil Rings, Road-Rite Balance (whatever that was), and Duomatic Spark Advance.

As I said, just perusing the car ads in old newspapers can consume an afternoon while you wait for the modern world’s latest crisis to fade. And learning that your car’s original owner has more of a story beyond just being your car’s original owner is immensely gratifying. As the old Buick sits in my garage in Los Angeles, I can now picture it waiting for Odessa in the parking lot at Hopewell Presbyterian, or sitting in the driveway at 469 N. Main, or at the State House in Indianapolis amidst the other Detroit streamliners of its day.

My car now has a life beyond simply being my car. First it was Odessa’s, and as a citizen of the distant future, I owe her a debt for having such good taste in automobiles, as well as a debt to the editors and writers of those newspapers for making sure her story wasn’t completely lost to time.