5 American vehicles with double lives in foreign lands

“And you know what they call a Quarter Pounder with cheese in Paris?” Vincent Vega asked rhetorically as he barreled down the road in a beater 1974 Chevy Nova with Jules Winnfield at the wheel. His fellow hitman was chuffed: “They don’t call it a Quarter Pounder with cheese?”

The conversation sparked up when Jules, who had spent most of his lifetime around the streets of Inglewood, California, let Vincent go on about his recent European travels and the little differences he noticed in daily life.

“No man, they got the metric system. They wouldn’t know what the **** a Quarter Pounder is,” Vincent retorts. “They call it a Royale with Cheese!”

Brute-force muscle cars, world-beating but affordable sports cars, and ever-dependable and reliable pickup trucks—surely our very own American delicacies, right? The funny thing about global industry is that parallel universes of nearly everything we buy and love here in the United States get remixed to suit other parts of the world, including our beloved domestic automobiles. Whether the changes were made to meet the production capabilities of another country or simply restyled to hide the roots of last year’s sedans, these machines of the mechanical multiverse have identities all their own. Here are, if you will, five automotive “Royales with cheese.”

Shelby de Mexico

Through the ’60s, the Mustang was practically unstoppable in showrooms. It dominated pony-car sales with a flavor-for-everyone approach that ran the gamut from straight-six economy cars to gas-huffing V-8 bar fights.

South of the border, Eduardo Velazquez Contreras had a plan to build an automotive empire after making his riches practicing law in Mexico City, where he was born and raised. Contreras had invested into a friend’s Chrysler de Mexico operation converting U.S.-market Valiants for the local market, but the 500-unit order into the country from Chrysler wasn’t exactly lighting the books on fire with profits. He next turned his attention to the burgeoning Volkswagen market after that company had begun its conquest of Mexico (later becoming the country’s most popular vehicle in total sales and eventually in domestic production volume), securing an exclusive parts deal with the European Motor Products Incorporated to import and supply replacement parts.

Shelby, however, would become his most famous partner.

In 1966, Contreras began first by importing Shelby parts into Mexico so that locals could spec up their Mustangs into a true “Gran Turismo” car, with authentic Ford cosmetic bits that were manufactured and sold in Mexico. This was just the first step for the enterprising businessman, though. Via negotiations with Carroll Shelby the following year, Contreras expanded his import activity to the GT350 in 1967. To clarify: not the whole GT350 from Shelby, but specifically the kit of parts that Shelby American used in its own conversions of the U.S.-built Mustangs.

These kits allowed Contreras to buy notchback Mustangs from the local factories in Mexico and then essentially carry out the same GT350 conversion Shelby was doing in its shop, except for one notable difference: no fastback. The Mexican factories only produced the standard, “notch” Mustangs, so for 1969, Contreras began work on the fiberglass buttresses to flank the trunk of his Shelby de Mexico Mustangs. This unique buttress had the side-profile of a fastback, but the recessed rear windshield was more reminiscent of a Dodge Charger or AMC Javelin.

Underneath, the Mustangs were a mixture of Shelby and Mexican-market Ford parts. The Mexican-built Fords already received beefier suspension components to deal with the huge expanse of rural, rough roads in the country, and Shelby’s recipe included its 10-spoke aluminum wheels, lightweight fiberglass panels, Shelby-specific suspension upgrades, chassis bracing, and all the appropriate accouterments to the Windsor small-blocks to help spice up the high-output 289s and 302s with minor bolts-ons. (Think dual-point ignition, tri-Y headers, an aluminum intake manifold from the Cobra, and the required Shelby branding.)

Production numbers, much less current survivors, are largely the stuff of legend by this point, but our research points to Shelby International, S.A producing approximately 678 cars. Allegedly, only six of the original 1969 flying buttress conversions remain, while most of the ’66 to ’67s have fallen off the radar. Of those half-dozen, the only one we could surface in a recent auction was this unit from Barrett-Jackson, which sold for a $49,500 in 2016.

Chevy 20-series

We Amurikans think we’re the only ones who hold the pickup truck in such esteem, but for the same reasons we love rough-and-tumble trucks, South America goes crazy for them as well. (Keep in mind that this region also has a larger dependency on rough country roads.) South America didn’t grow its own widespread domestic auto industry, but it did benefit from partnerships with many North American companies, such as General Motors. For the most part, GM in the U.S. handled the core engineering and parts production before components were married to their South American-spec bodies, as was the case for Chevrolet and GMC trucks throughout GM’s history in Latin regions.

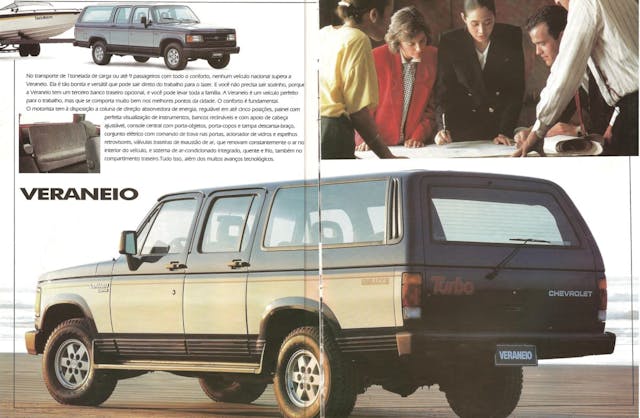

The 10 series was originally based on a unique South American-spec chassis and body, but in 1985, it converged with the familiar 1973 to 1987 C/K-series trucks and SUVs as the new 20 series (also known as the Bonanza and Veraneio in Blazer and Suburban form). At first glance, the 20 series, and its variations, look like a generic SUV model out of Grand Theft Auto or some other game that doesn’t want to pay licensing fees. Bits like the roof and A-pillars look familiar, and maybe the cutout for the side glass seems recognizable, but below the beltline, it’s all-new sheet metal for the 20 series.

Assembled in Brazil and Argentina, where GM had a foothold in South America, the 20 series could be found with either a late-version of the 250-cubic-inch Stovebolt six (which saw a second life down south to heavy regulations and taxes on larger displacement V-8s), or a 3.9-liter Perkins diesel, which was eventually replaced by a turbocharged Maxion mill. The C, D, and A prefix align with the fuel type (gasoline, diesel, and ethanol, respectively); in the U.S., C and K refer to 2WD and 4×4 chassis.

South America would eventually adopt the C/K nomenclature for the GMT400 in 1997, along with the US-spec body, but it would once again deviate from the US trucks mechanically. They carried their own line-up of engines, with the Stovebolt returning for its last appearance along with a new MWM 4.2-liter inline-six diesel engine updating the oil-burning option, and they also utilized a unique mix of 1973 to 1987 front suspension components under the newer GMT400 in order to utilize the massive stock of Square Body repair and maintenance parts produced by the local factories. The GMT400 was practically a clean-sheet design, thus it would have been a major undertaking to update the South American supply chain for the new-to-them platform (which was due to be replaced in 1999 by the GMT800, anyway).

The irony here is that the General Motors heavily leveraged South America in their Pan American record attempt from Argentina’s Tierra del Fuego to Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay, piloted by Gary Sowerby and Tim Cahill, in order to promote the brand-new GMT400 heavy-duty trucks with the 6.2-liter Detroit Diesel and Muncie SM465 four-on-the-floor. The route was more than just an endless climb, it was a massive marketing adventure as the two made their way North through South America and into Mexico while leveraging a multitude of GM and local contacts in Latin America in order to get the 1988 GMC Sierra 3500 across corrupt border checkpoints and treacherous cliff-edge roads, making a big splash along the way in major cities with the kinds of police escorts and fanfare usually saved for idolized politicians — only to receive the GMT400 nearly a decade later that was, for the most part, little different than the locally-built 20-series of yore.

Willys Aero

Speaking of Willys, Kaiser, and AMC, back in the day these now-defunct automakers were often up against the unstoppable forces of the Big Three’s incredible production, marketing, and design resources. In various niches, each of these underdog automakers broke barriers that wouldn’t be challenged for another decade or two, but a combination of the wrong-place-wrong-time situations, along with leadership challenges spurred by the cyclical dissolving and reconstituting of these three brands, ultimately conspired to cut short the legacies of several models for U.S. consumption.

Where one door closes, another one opens—and for South America, the death of a car in the U.S. market was a chance to buy every bit of tooling needed to create slightly modified domestic vehicles. Machines like the defunct Willys Aero were craftily spun off into affordable, local favorites.

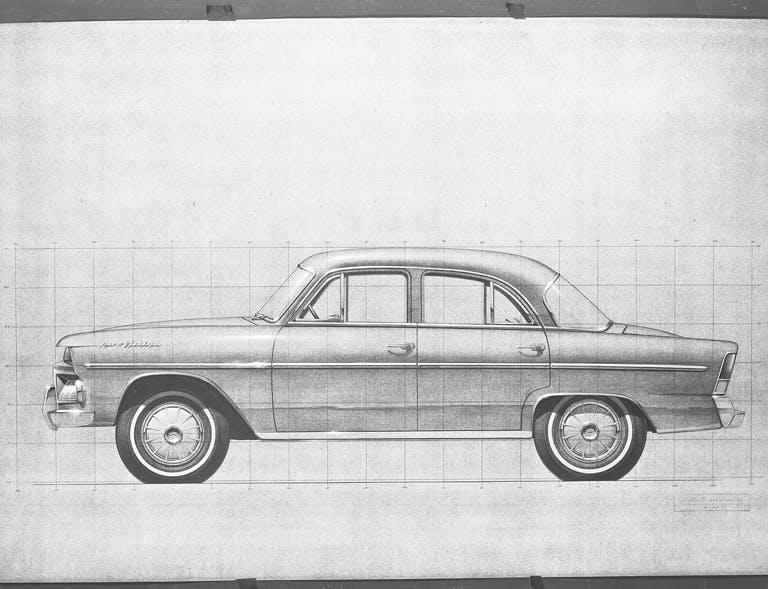

For all its forward-thinking in size and economy, the Aero was essentially a failure as far as sales volume. Launched in 1952, the Aero never surpassed 100,000 units out of its Toledo, Ohio, assembly plant before Kaiser came into the mix to kill everything off in 1955. Willys had designed the Aero to be a do-all economy car based around the familiar Jeep Hurricane flathead-six, sitting nearly a foot shorter than many of its American compatriots at the time (such as the Chevrolet 210). It was a hard sell to cut V-8s from the line-up at a time when the Big Three were meanwhile building an image of style and performance.

Kaiser had acquired Willys in 1952, a year after the Aero lineup of sedans and coupes had launched, before deciding to exit the automotive industry as a whole. Only Jeep survived the transition. It was at this pivotal moment that led Industrias Kaiser Argentina (IKA), formed in 1956, entered the picture. IKA picked up the Aero’s production in Brazil by scooping up every bit of tooling: the dies and molds for the body and trim, the jigs for the frames and anything else it could, in 1958. The Brazilian Aeros began production in 1960, with about half their components imported from the U.S., but would bring everything in-house, including a styling refresh by Brooks Stevens by 1963.

For those first few years, the Aero was practically identical to its U.S.-built cousins, but as details like the interior and much of the chassis’ supporting hardware had moved to Brazilian components, the Willys’ identity had been slowly replaced by IKA’s. This would essentially mark the IKA Aero as Brazil’s first production car, even though it was initially designed and engineered in America. Production would continue with minor updates until 1971, when the then-Ford-owned Willys Aero finally retired.

IKA/Renault Torino

Designed in the United States, restyled in Italy, and sold in Argentina, the IKA Torino was a pure international affair. IKA, Kaiser’s Argentinean subsidiary, was practically commissioned in 1951 by the Argentinean government to shop an import and production plan with the major American OEMs. Kaiser ultimately took the bait to supply its own cars alongside the Willys Jeep after Argentina’s burgeoning (but still small) automotive market was deemed too low-volume for any of the Big Three to justify a partnership.

By the 1960s, IKA had worn through Kaiser’s aging 1950s platforms and was looking for a new donor when Dick Teague penned the new-for-1964 AMC Rambler American in the United States. The clean-sheet design dialed back the frumpy post-war Edmund E. Anderson design of the prior generation Rambler American for a sleeker, more stately profile that came to define the automaker’s styling in the 1960s.

To bring the Rambler American to market, IKA first shipped it to Pininfarina to have the space-age styling toned down in favor of a classic European affair. The refrigerator-like front grilles were removed to make room for a taller opening flanked by a pair of fog lamps. The turn signals were moved onto the body so that the bumpers could be trimmed down into more subtle bumperettes, while the hood was also lightly reshaped. Larger, slightly rounder tail lamps were complemented by another bumper diet, adding extra character to the no-nonsense styling of the Rambler American’s tail.

Underneath, IKA largely carried over the U.S.-spec chassis, but in lieu of big-inch V-8s, the IKA Torino utilized the overhead-cam inline-six from Jeep. The venerable “Tornado” straight-six had its block beefed up, while the heads were opened up with a triple Webber DCOE setup in its top-performance trim. This gave the Torino real chops in road racing, owing to its relatively low weight and healthy power—nearly 190 hp out of the refined Jeep mill.

In fact, the Torino dominated the 84-hour Marathon de la Route endurance race at the Nürburgring, with the factory-backed assault on the Green Hell managed in part by none other than Juan Manuel Fangio. The famous racer’s roots in Argentina catapulted IKA’s status as the “national car of Argentina” as drivers Eduardo Copello, Oscar Mauricio Franco, and Alberto Rodriguez Larreta won their class and settled at fourth-overall after penalties. Fangio was also later gifted a 1970 IKA Torino 380S as something of a “thank you” for his efforts. That car sold for approximately $45,000 in 2012.

The humble AMC Rambler American would go under one final rebadge, when IKA merged with Renault in 1975, spawning the Renault Torino—the car’s final form as a French-owned, Italian-styled, American-designed, and (taking in another breath) Argentinean-built sports coupe.

GAZ A/AA

Without a doubt, if the Ford Motor Company had never approached Moscow to start hawking Model Ts at the start of the 20th century, Russia would have struggled to develop as a world power the way it did. It’s hard to imagine life in the U.S. a hundred years ago, much less in pre-World War II Russia as communism swept the country with promises of a “bright future.”At the time, this was a land that in general lagged behind the industrial revolution that had mechanized the U.S. and much of Europe. Russia’s relationship with the Western world has always been tenuous, but in the early days of post-revolution Russia, the country connected with the Ford Motor Company to fulfill a need for a mass of tractors: the Fordzons.

Ford had opened a Moscow sales office in 1909 as it began its international conquest. Henry’s new-age assembly-line ethos, by that point, had yielded sufficient production capacity to begin export efforts in earnest. The War Ministry was Ford’s largest customer initially, with officials enjoying the capabilities of the American-built machines, but a small event known as the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, and its subsequent chaos, distracted Ford and the Russian Empire from their import/export dreams.

After the USSR was established in 1922, talks quickly resumed. Ford continued bringing in vehicles, while the interim Bolshevik government used shell organizations and proxy contacts to begin building ties in Washington and Dearborn in 1919. One of those contacts was one L. Marten, an engineer who had been exiled from Russia for his pro-revolutionary views prior to the civil war. Marten’s mission was to begin establishing a source of tractors for the USSR in order to rebuild the economy and jump-start Russia’s own industrial revolution. Ford has applied its mass production methods for automobile to tractors, which made it cost-effective to import for the USSR thanks to their low unit cost out of U.S. factories.

Moreover, Marten came back with a genuine appreciation for Henry Ford’s vision. “The Ford tractor will be the ideal machine for the communist farms in Russia,” Martens reported. “In addition, I hope we will be able to convince Ford to build a plant in Russia for the production of tractors and cars. We are also promised assistance in passing several hundred Russians through the Ford tractor school in order to train experienced instructors for Russia. These will, of course, be our people.”

Ford’s tractors imported to the USSR quickly began to outpace the sales of its cars, with nearly 20,000 of the iron horses delivered into the hands of the Soviet people within the first few years. It became clear that domestic manufacturing would be vital to maintaining the supply, training, and repair of Ford tractors, and so the Soviets approached Ford to help build the USSR’s first-ever automotive factory.

The process was arduous, for many reasons. Ford had sent over a five-person commission to study the government, its people and culture, as well as current Ford customers. The goal was to ascertain if the proposition was not only good business sense but if it was compatible with the collective mindset required for an assembly line to properly.

Their report reads like a school kid’s field trip report, with absolute wonder and confusion over a world they hadn’t seen before. While optimistic, the report was largely unimpressed with the state of industry in the Soviet Union, and it classified the findings in secrecy to stave of Soviet espionage. Ford staff was worried that the Soviets could become offended by their unfiltered opinions, jeopardizing future travel visas and business opportunities. Diametrically opposed in their backdrops, the American commission was disappointed in the lack of organization, discipline, and forethought with the USSR’s factories, and in conflict with Ford’s philosophy, hand fabrication of both production and spare parts was still common. Worse, the USSR emphasized the need to be able to buy parts and whole vehicles on credit, at a national level, in order to recoup the costs with their produced goods down the line. This proposal put a large financial risk upon Ford to fulfill the large orders, especially with the USSR’s tight grip on pricing and production, but the Soviets were at the end of the day Ford’s largest customer outside of the U.S.

Ford’s commission came back to the Soviets with a careful plan that emphasized local support for farmers in the form of parts and repair shops. It was a total rework of the behavior of port workers (who often left Ford’s imports to rust in the sea air or dropped them onto the ground, crashing from the deck of a rail car), meant to instill a sense of pride in the engineering by creating permanent displays for Ford machinery. The relationship ebbed and flowed as competition from International Harvester entered the fray, but by 1927, Soviet leadership had entered into steady discussions to potentially build a Ford factory in the USSR.

In May of 1929, an agreement between Ford and the USSR officially created GAZ: Gorkovsky Avtomobilny Zavod, or, the Gorky Automotive Plant. The USSR would build two factories: one in the Russian town of Nizhny Novgorod and the other in the capital city of Moscow. The Soviets would supply the raw materials to construct the facilities while Ford brought to the table its intellectual property, production machinery, and industry experts to oversee the new factories.

GAZ would produce three basic models (A, AA, MM) centered around the Model A body, supplementing the Soviets with everything from touring cars to troop carriers before the partnership mutually dissolved in 1935 as the Great Depression set in. Though Ford recorded many productivity and craftsmanship problems given the region’s complicated bureaucracy, largely untrained labor force, and sub-par metallurgy, these facilities and the lessons learned within them nonetheless proved vital to Moscow’s rise as an industrial power heading into World War II.