Galleria Della Ferrari: 18 images celebrating 75 years of the Prancing Horse

Enzo Ferrari opened his namesake scuderia in Modena, in 1929. It took 18 years for the future automotive titan’s name to grace the nose of a road car—the Ferrari 125 S. In the three-quarter-century since, the Prancing Horse has become synonymous with ultra high performance, timeless style, and motorsport prowess. For many both in and outside of the automotive know, Ferrari is the pinnacle.

To celebrate 75 years of Ferrari as a formal automaker, we’ve assembled this diverse roster of snapshots from the brand’s history. The company’s sterling legacy is the product of its cars, racing exploits, cost-no-object engineering, personalities, and devoted fans. Take a few minutes to relive it all.

Lusso

“Lusso” means “luxury” in Italian. It means “gorgeous” in Ferrari. Many consider the Pininfarina-designed 250 GT Berlinetta Lusso to be Ferrari’s most ravishing road car. Within its graceful fuselage was the final iteration of Gioacchino Colombo’s 250 V-12, a racing mill mellowed for the road. As a 34th birthday present, Neile Adams bought a chestnut brown Lusso, No. 4891, for her husband, Steve McQueen. It was that kind of car.

Ferrari 312T

Pole-sitter Niki Lauda takes flight at the Nürburgring Flugplatz in the 1975 German GP, on his way to his first world championship. It was a year in which it all came together for Ferrari, with a dominant car, a flat-12 engine designed by the brilliant Mauro Forghieri, Lauda “The Computer” at the wheel, and team manager Luca di Montezemolo, Ferrari’s future CEO, providing a steady hand. A year later, Lauda nearly died at the same circuit in a fiery crash, permanently ending Formula 1 racing on the ’Ring’s famous 14.2-mile Nordschleife.

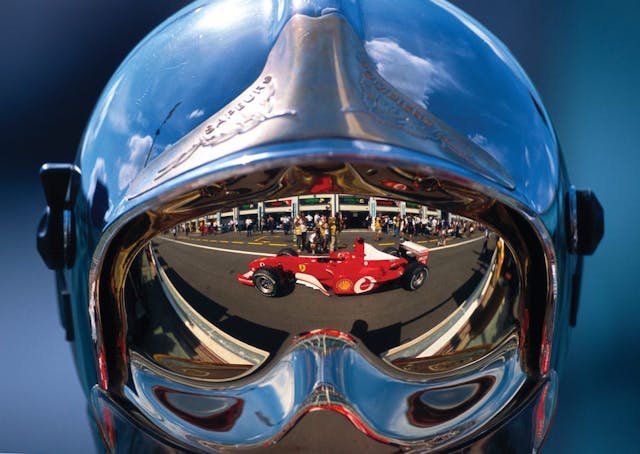

Michael Schumacher

Ferrari’s single greatest period of F1 domination was at its peak at the 2002 French Grand Prix at Circuit de Nevers Magny-Cours. Ferraris driven by Michael Schumacher and Rubens Barrichello won 15 of the 17 rounds that season. Schumacher, whose 3.0-liter V-10–powered F2002 is reflected in the helmet visor of one of the circuit’s sapeurs-pompiers, or firefighters, was on his way to winning his fifth of seven world champion titles.

250 GTO

For many, the 250 GTO is the quintessential Ferrari, a euphoric mix of voluptuous styling and savage V-12 performance. Launched by Giotto Bizzarrini and later developed by Mauro Forghieri, the GTO was a homologation special (hence the O in its name, for omologoto), conceived as a semi-practical production coupe hiding a full-bore track weapon. With only 36 built, it flouted the 100-car production requirement at the time, yet it became the last front-engine machine to dominate sports car racing.

Turbo Formula 1

Ferrari’s fortunes in F1 crashed in the turbo era, known for its 1500-hp monsters as well as its pyrotechnic turbo failures. The Scuderia won but one race in 1984, and the following year, the Ferrari 156/85, pictured here at Monaco with its 1.5-liter turbo V-6 spitting flame on its way to second place, only managed two wins (and 11 retirements) at the hands of Michele Alboreto and Stefan Johansson. After that, Ferrari went into a 37-race slump as Honda returned to F1 and conquered all.

Scuderia Ferrari

Ferrari’s dedication to the sport is summed up in this one photo of the team’s chockablock garage at the 12 Hours of Sebring in March 1962. In the distance: the No. 23 250 TRI/61 that would win overall. Not pictured: the No. 24 NART 250 GTO crewed by Phil Hill and Olivier Gendebien that marked the GTO’s racing debut. It finished second. Enzo Ferrari only reluctantly joined the migration to mid-engine layouts, long clinging to the notion that “the ox always goes in front of the cart.”

La Ferrari

It was the successor to the Enzo and the lineal descendant of the F50 and F40. As such, the La Ferrari arrived in 2013 as a $1.4 million limited-production special intended as a styling and technology showpiece. The 6.3-liter V-12 was Ferrari’s first roadgoing powerplant to incorporate a hybrid-electric drive, the unit delivering 950 horsepower and 60 mph in 2.5 seconds.

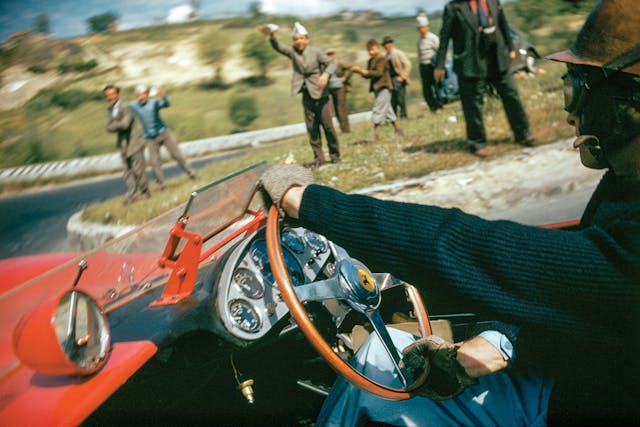

Mille Miglia

Famed motorsport photographer Louis Klemantaski snapped Peter Collins racing toward Rome in a Ferrari 335 Sport in the 1957 Mille Miglia. Klemantaski served as Collins’s navigator as well as a photo documentarian of the final Mille Miglia. Authorities banned the event after Alfonso de Portago plowed another Ferrari into a crowd, killing himself, his navigator, and 10 spectators. Collins died a year later in a Ferrari in Germany, one of a number of crashes in the period that decimated the Scuderia.

Targa Florio

Though racing on public roads largely disappeared in the 1950s, Vincenzo Florio’s original 1906 sprint around Sicily somehow managed to survive until 1977 despite repeated fatal incidents. Here, the No. 6 Ferrari 512S of Nino Vaccarella and Ignazio Giunti blasts through the ancient stone villages at Le Mans speeds during the 1970 running, nothing but hay bales separating the cars from the crowds. This lone factory entry finished third, turning 11 laps of the 44-mile circuit.

F40

Enzo Ferrari himself pulled the sheet off the F40 in 1987, saying he had tasked his engineers with building “a car to be the best in the world.” The twin-turbo 478-hp, 197-mph supercar car was the best—and still is, according to many. In the mold of the stripped-down sports-racers of Ferrari’s early years, the $400,000 F40 was intended to go from showroom to track with few mods. Enzo died a year later, igniting demand (1315 were built) and resale prices.

John Surtees

When he joined Ferrari in 1963, “Big John” Surtees was already a name in Italy for bagging the GP motorcycle world championship for MV Agusta. Naturally gifted, tireless, and utterly fearless, he was instantly a contender on four wheels and revived Ferrari’s fortunes as it chased Lotus and BRM. In 1964, the Scuderia returned with the new V-8–powered 158, and though Surtees won only two races, he nicked the championship by a single point, making him an Italian national hero.

Gilles Villeneuve

Enzo Ferrari demanded devotion from his drivers as well as unflinching courage. A former snowmobile racer from Quebec, Gilles Villeneuve had all those qualities, plus enough raw talent to vault him to the highest level of motorsport without any help from a family fortune. From the moment he joined Ferrari in 1977, he drove flat-out, taking his stiff ground-effect cars to the edge of control—and sometimes beyond.

Enzo

The Old Man, Il Commendatore, Mr. Ferrari. Whatever people chose to call him, they did so with respect. The son of a metalworker from Modena, Enzo Ferrari was a commoner who built an empire to which aristocrats and dilettantes came on bended knee. A ruthless competitor and weaver of political intrigue, he sold cars in order to race, though he almost never attended races himself. He died in 1988, as much an enigma as a legend. The car they chose to honor him with in 2002 was equally complex, a 651-hp, $659,000 statement of the Scuderia’s accumulated knowledge and technology.

Le Mans

When buyout negotiations between Ford and Ferrari fell apart in the summer of 1963, Henry Ford II is reputed to have said, “OK then, we’ll kick his ass.” By 1967, the onslaught was in full swing, the modified Ford GT40 Mk IVs gunning for a repeat of the ’66 Le Mans win. Here, the Ferrari 330 P4 of Günter Klass and Peter Sutcliffe pits during the ultimately futile effort to salvage Ferrari’s honor.

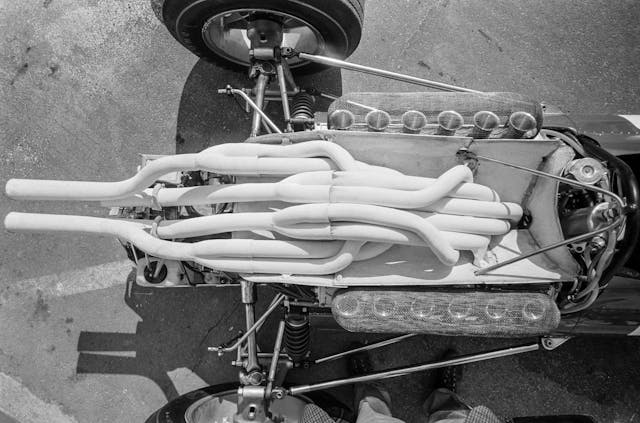

Spaghetti

The famous coil of white pythons on the back of a Ferrari F1 car first appeared in 1966, when the rules doubled displacement to 3.0 liters and Ferrari was quick off the mark with its V-12–powered 312. The 1967 car, pictured here, was an improved version. Despite the heady power and wailing song from this Italian pipe organ, the season was a disaster, with the death of Lorenzo Bandini at Monaco and Chris Amon only managing fifth in the championship.

F50

It’s a gross understatement to say the F40 was a hard act to follow, but an open roadster with an F1-derived, naturally aspirated, 8500-rpm V-12 that could eat 60 mph in 3.8 seconds certainly managed. The 1995–97 F50 was a child of its moment, after speculators had driven Ferrari prices to the stratosphere and damaged the brand. Only 349 were made, all initially leased by application to prevent flipping. Rarely seen in the wild, the F50 birthed a whole new genre of limited-production, hyper-exotic supercars.

The Tifosi

Like the Roman Colosseum or Sophia Loren, Ferrari is an Italian icon that its people claim as their own. Ferrari helped resurrect Italy’s self-esteem after a devastating war, and without Ferrari, F1 would probably have ceased to exist long ago. When Ferrari wins, it’s a national holiday. When it loses, the recriminations are vicious. Unbridled passion is what sustains Ferrari—and also what makes it so Italian.

Sharknose

By 1961, when the FIA cut the engine displacement in F1 down to 1.5 liters, the sport was dominated by the small-fry British garage teams of Cooper and Lotus, which innovated with disc brakes, coil springs, and engines behind the driver. Ferrari finally responded with the rakish Tipo 156, a twin-nostril Brit hunter with a 120-degree V-6 that Phil Hill piloted to a fateful world championship.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.