New Ford GT book is the ultimate history of racing’s most unlikely rivalry

There has been a lot of buzz surrounding the upcoming Ford v Ferrari film, especially since the second trailer just dropped a week ago. With excitement, we recently dove into the book Ford GT: How Ford Silenced the Critics, Humbled Ferrari and Conquered Le Mans by Preston Lerner, with historical photography by Dave Friedman. The book covers the story behind Ford and Ferrari rivalry, the GT40 program and its development, early teething problems, and ultimately dominance at Le Mans in the latter half of the 1960s.

If you plan to see the film in November, consider this required reading. Here’s an excerpt from this phenomenal book, which you can order here.

April 1967 – June 1967

Survival of the Fastest

The 24 hours of Le Mans is the greatest sports car race in the world. Period. None of the pretenders to the throne can rival its history, its heritage, its impact, its variety—the action on the track, the drama in the pits, the parties in the grand-stands, the spectacle in the infield. And yet, as much as Le Mans deserves its reputation, the 24-hour enduro doesn’t always produce great racing. Some years, no interesting cars show up. Other years, the competition fizzles. It can be wet and cold and thoroughly miserable, and on those occasions, everybody—the drivers, the mechanics, the fans, even the vendors—can’t wait for the race to end. The winners are inscribed on the roster of champions and the legend of Le Mans grows by accretion. But the race itself—an interminable slog twice around the large clock cantilevered over the pits—is quickly forgotten.

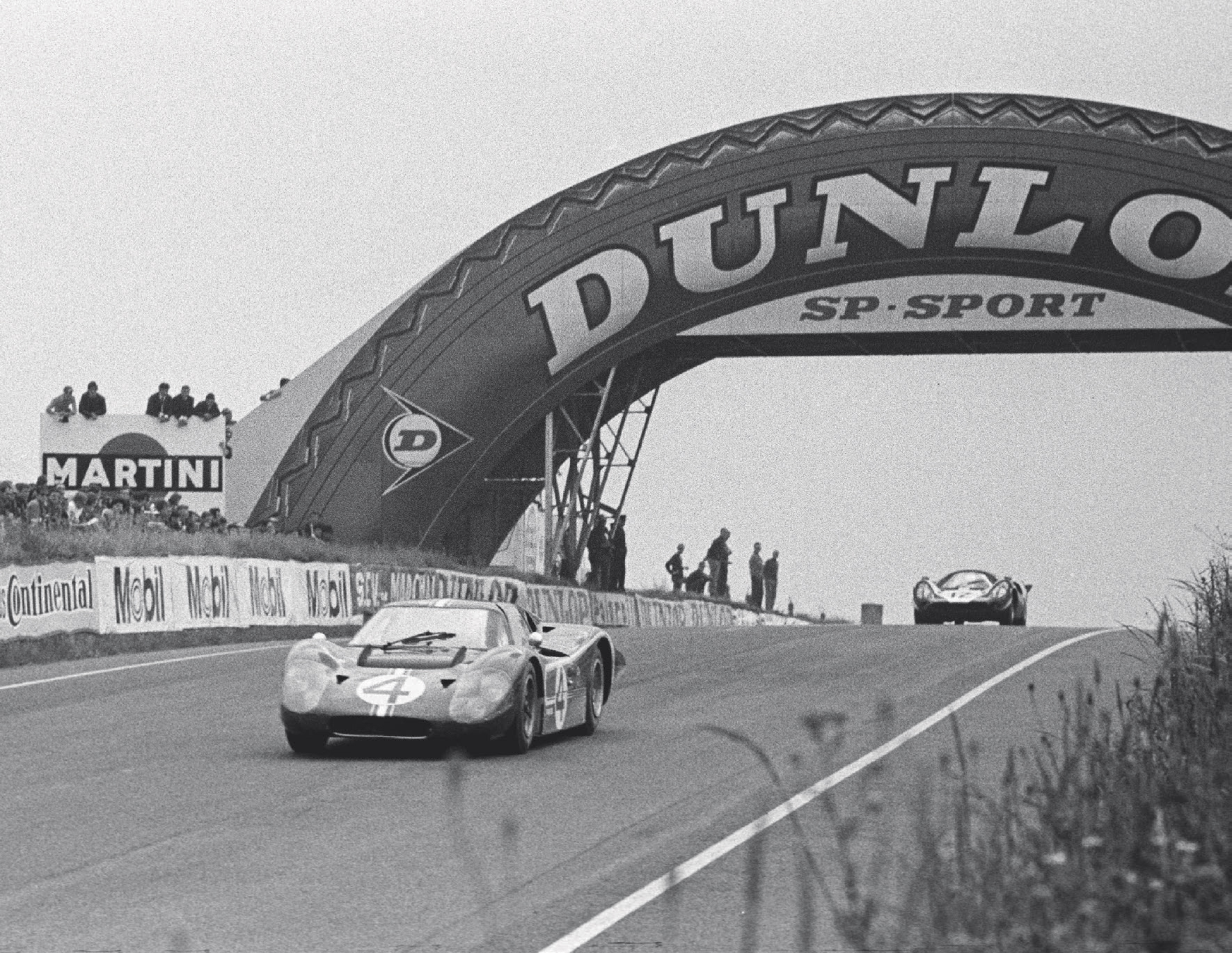

In 1967, though, Le Mans was shaping up to be something memorable. Head-to-head battles weren’t unusual at the Circuit de la Sarthe. But this year promised a dogfight between three bitter enemies campaigning four vastly different models of prototype sports cars that would go on to become icons of the 1960s—the sensuously snarling Ferrari 330 P4, the fantastically winged Chaparral 2F, the once all-conquering Ford Mark II, and the exotic but largely untested Mark IV. The field included seven Ford prototypes, seven Ferraris, and a pair of Chaparrals. Ten or so cars had a legitimate shot at winning.

The driver lineups were equally impressive. With its deep pockets and broad-based racing program, Ford had access to just about anybody it wanted. Among its 12 drivers at Le Mans were two who would go on to win F1 world championships (Mario Andretti and Denny Hulme), three who had won or would win Indy 500s (Andretti, A. J. Foyt, and Mark Donohue), four who had won or would win F1 races (Andretti, Hulme, Bruce McLaren, and Dan Gurney), and seven who had won or would win Indy car races (Foyt, Donohue, Andretti, Gurney, Lloyd Ruby, Roger McCluskey, and Ronnie Bucknum). Driving various Ferraris were three F1 winners (Ludovico Scarfiotti, Pedro Rodriguez, and Giancarlo Baghetti) and Chris Amon, who’s universally regarded as the finest driver never to have won a World Championship Grand Prix. Also, former F1 world champion and three-time Le Mans-winner Phil Hill was in a Chaparral.

So the racing community was eagerly anticipating a clash of the giants. And the race would go on to be even more gripping than expected. “The 1967 Vingt-Quatre Heures du Mans was one of the finest contests I have ever witnessed,” wrote John Bolster, the venerable Autosport editor rarely seen without his deerstalker hat. “I followed the whole race from the pits, and I was so enthralled that I almost forgot to eat. Nothing could drag me away from that titanic struggle. This was motor racing at its best, with perfectly prepared cars, efficient pit crews, and, in most cases, excellent drivers. Whether the greater credit goes to Ford or Ferrari it is difficult to say, but both teams are to be congratulated on really going motor racing.”

But at the same time, an unsettled mood hung over the proceedings. In the pits and the paddock, there was a sense that this might mark the end of an era of unrestrained development. After Ford dominated Le Mans in 1966, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile had made noises about changing the regulations to limit engine size or require four seats or even extend the number of laps that had to be completed before pit stops. Any one of these rules would have rendered the 7.0-liter Fords instantly obsolete. In the end, nothing was done, and Ford was already planning to upgrade the Mark IV for 1968. But the FIA was scheduled to meet a week after Le Mans, and action on the rules was obviously possible. So Ford was determined to empty its tank at Le Mans.

Judging by the number of people it included and the logistical support they necessitated, the Ford operation seemed less like a race team than an expeditionary force assembled to establish a beachhead in enemy territory. “It’s hard to describe the Ford setup because it’s so gigantic and they spend so much money,” Shelby American driver Paul Hawkins wrote, “but they produce the best cars that money could buy to do the job Ford required them to do. And that is to win Le Mans. They had taken over half a big Peugeot garage in Le Mans, fitting it out with their own coffee and Coca-Cola machines, and they had even flown their own drinking water over from America! They had a big semi-trailer done out as a mobile workshop, and I’m sure they would have flown that over too if they could have found a big enough plane. They even had their own toilet paper specially brought over from the States. We were looked after like kings—the best hotels in Le Mans, special caterers at the circuit, and caravans for us to sleep in out there.”

According to Ford documents, there were 12 drivers and two reserves. Shelby American and Holman & Moody each had four administrators, two fabricators/machinists, and a parts guy. Shelby American brought 11 mechanics; Holman & Moody, 12; and Kar-Kraft, a 24th. The teams shared an engine specialist and a truck driver. Holman had three extra people performing various tasks. There were also three men assigned to the service truck. In addition, Ford brought a timing-and-scoring (and signaling) crew of 18, plus 35 Ford employees from top executives down to working engineers. Many of them traveled with their wives. This list didn’t include Henry Ford II and his considerable entourage or the official team doctor and the helicopter pilot who’d been retained to fly, if necessary, to the military hospital in Orleans (where Walt Hansgen had died). Al-together, there were more than 125 people, and, as David E. Davis observed wryly in Car and Driver, “They were hard to miss.” Which was precisely the point.

As a corporation, Ford understood—and this was a lesson that would be taken to heart by other manufacturers in years to come—that racing was primarily a marketing tool. Developing new technology was all well and good. But the principal purpose of motorsport was burnishing the brand image. Thus, according to an internal memo, “Prior to leaving Los Angeles, all crew will obtain a neat haircut and are required to shave daily while in France and maintain a high degree of personal appearance at all times, as we all represent the U.S.A. and the Ford Motor Company.” No fewer than three public relations specialists were attached to the team. Besides mimeographing and distributing hourly updates to the press, they were ordered to pay personal attention to specified journalists.

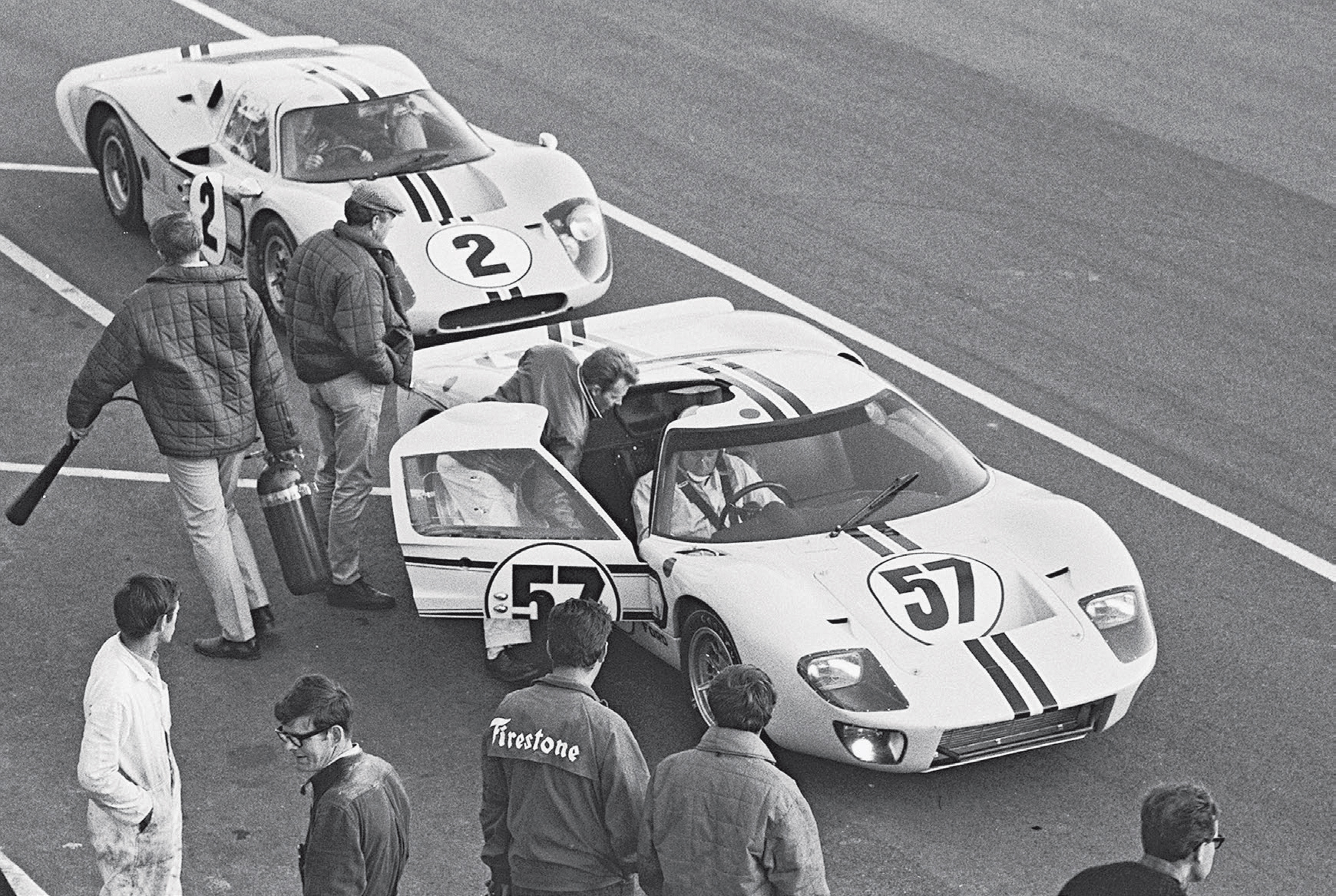

Ford entered four Mark IVs and three Mark IIBs. The Sebring winner—J-4—had been retired, and four strengthened Mark IV tubs had been built for Le Mans. Holman & Moody put Andretti and Lucien Bianchi in one of them and Hulme and Ruby in another, while Frank Gardner and McCluskey shared a Mark IIB. Holman & Moody was also in charge of a second Mark IIB driven by Jo Schlesser and Guy Ligier, though Ford France was technically the entrant. Shelby American’s driver pairings were Foyt/Gurney and McLaren/Donohue in Mark IVs and Bucknum/Hawkins in a Mark IIB. There were also three privately owned GT40s and two Mirages—light-weight variations on the GT40 theme—entered by the team John Wyer had formed after severing official ties with Ford.

The marquee driving combo was Gurney and Foyt. Gurney, who would become the first American to win a modern Grand Prix (at Spa) in an American car the week after Le Mans, was the best-known American in international competition. Anthony Joseph Foyt, meanwhile, was the best-known driver in America. Two weeks earlier, he’d won the Indy 500 for the third time in seven years. Strong as a bull and brave as a bull rider, Foyt was the man to beat in Indy cars, sprint cars, and midgets, on pavement or dirt, from primitive bullrings to 200-mph super-speedways. In years to come, he would win Indy a fourth time, win the Daytona 500 in a stock car, and, when he was 50 years old, win Daytona and Sebring in the same year in a Porsche 962. Born near Houston and known as “Super Tex,” the drawling, self-assured Foyt was a curiosity in France. When he was served a plate of trout almondine, he sent it back because, he informed the waiter, he didn’t eat anything with the head still on it. But nobody mistook him for a rube. “Some people are born to fish,” he told the press. “Not me. I was born to race.”

Then again, Foyt didn’t have much road-racing experience, and he’d never been to Le Mans. Neither had Ruby or McCluskey. Ruby, at least, had plenty of seat time in sports cars. McCluskey was a talented driver who would retire with USAC Champ Car, sprint car, and stock car titles to his credit. But he’d been brought in at the last moment to replace Ginther, who’d retired unexpectedly, and he was unprepared for Le Mans. Plus, he was unnerved by the race circuit, which was ringed not by walls or guardrails but by stout-looking trees. McLaren told him that they were French safety barriers. “By the time a car got through them, there weren’t any pieces big enough to hurt the crowd!” he joked.

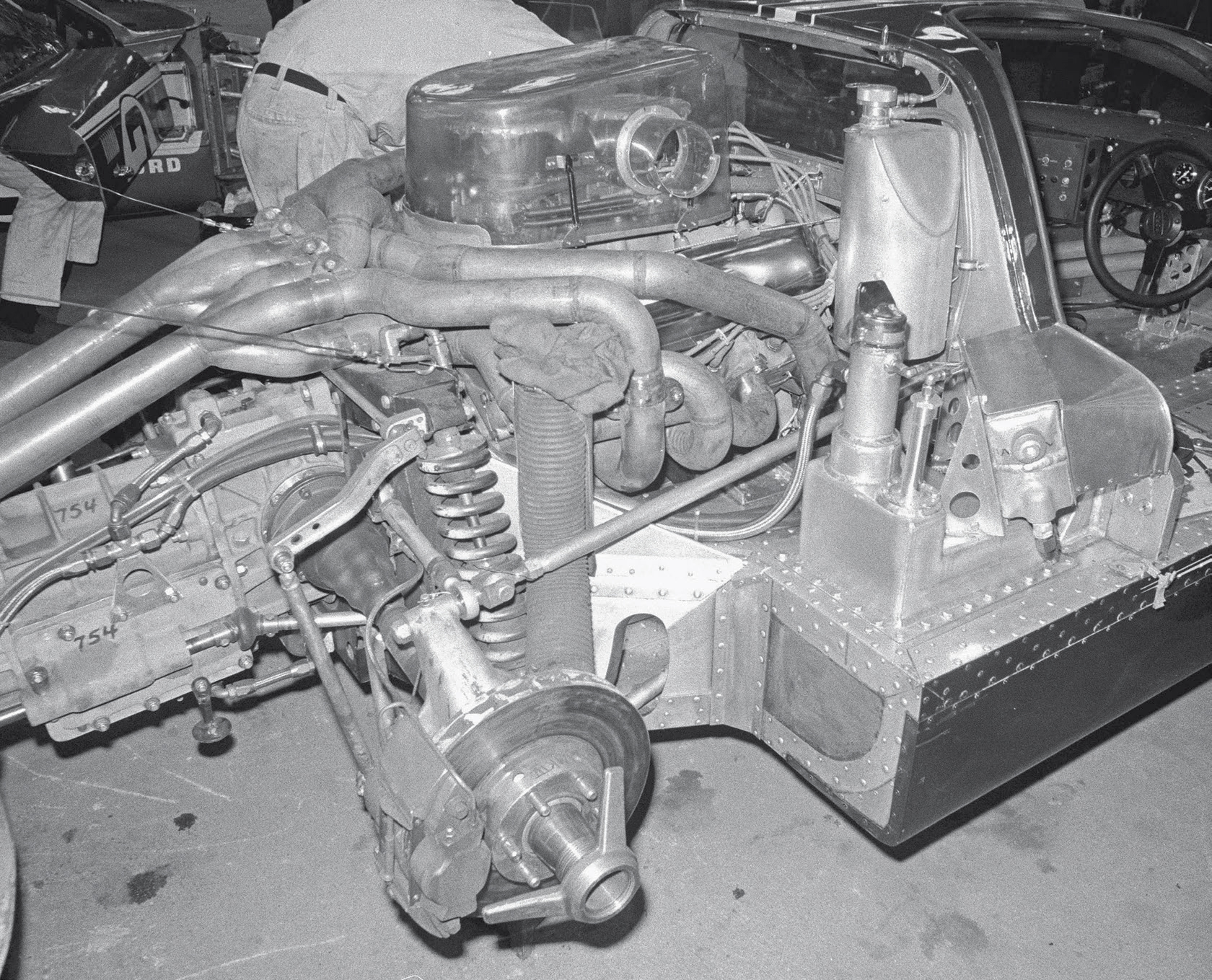

Ford engineers continued development right up until Le Mans. It had been decided, once and for all, to return to the aluminum heads to save weight. To claw back some of the lost horsepower, the engine mavens experimented with a tunnel port intake manifold. This maximized peak horsepower, but the NASCAR-spec open plenum performed poorly at low and medium engine speeds during the Le Mans Test. So the team installed an “over-and-under” intake manifold—what’s now called a dual-plane intake—with a 652-cfm four-barrel Holley with secondary cam plates and longer-stroke accelerator pumps feeding each half of the split plenum. At a final pre-Le Mans test at Daytona in May, the modified engine accelerated crisply from 3,000 to 6,500 rpm and worked better on downshifts. Peak output was 500 horsepower at 6,400 rpm (up from 485 in 1966), while torque rose from 450 to 470 lb-ft at 5,000 rpm. As always, power wasn’t the major objective, durability was. A test engine was hooked up in Dyno Cell 17B and run at a simulated lap speed of 3:30, with shift points at 7,000 rpm and holding 6,500 rpm on the Mulsanne straight. The goal was 48 hours without stopping. The longest the engine ran was “only” 45 hours and 15 minutes. Sold! Ten engines were built to the same specifications.

A host of other upgrades were made before the cars were sent to France. Brake pads were burnished on a brake dyno so they wouldn’t have to be bedded at the track. The brake ducts next to the grille were blocked off because it was felt that the cold air would “shock” the rotors into cracking during the vicious braking at the end of the Mulsanne straight. Instead, air was allowed to warm up while passing through the radiator ducts sunk into the hood before being routed to the brakes. Meanwhile, the crossover fuel system was revised so that cars could be gassed up in 17 seconds rather than the 68 seconds it took before. Various materials were improved (the CV joints in the half-shaft, for example) or made stronger (rear brake caliper bosses). Each of Ford’s seven Le Mans entries was painted a different color. The most distinctive was car No. 1, driven by Gurney and Foyt, which was dressed in bright red livery and which had a bubble in the roof to accommodate the helmet worn by the lanky Gurney. After all was said and done, the Mark IVs were only about 75 pounds lighter than the Mark IIBs, and the Holman & Moody cars were about 75 pounds lighter than the Shelby American entries.

20190926151504)

20190926151515)

20190926151553)

20190926151600)

20190926151608)

20190926151617)