Here’s why the Continental Mark II should never be called a Lincoln

In the early 1950s, there was a change of occupants, and ideas, at the Ford Trade School in Dearborn. Closed in 1952, it wasn’t long before the buildings were occupied by a clandestine Special Products Division, a name Ford gives fledgling new car developers. Edsel wore the name next; the gymnasium was turned into a clay modeling studio and the classrooms into drafting rooms and offices.

The Ford Trade School had taken young men off the streets, tested them for aptitude, and funneled them into Henry Ford’s workforce, all the while housing, feeding, clothing, and educating an urban, unskilled army of workers. They were taught work skills and academics part of the day and then worked on the factory floor. While child-labor laws would not permit this today, it was a very effective way to build an educated workforce.

William Clay Ford was tasked, at 28, to form a new Ford division and produce America’s premiere luxury coupe based on the successful Lincoln Continental that had been originally built in 1939 as a custom car for his father, Edsel. It’s often referred to as a “Mark I”—erroneously, since that has never been used by Ford internally, or in any parts or service manuals. The new offering was to be inspired by the dimensions of the Lincoln Zephyr-based Lincoln Continental and the current Lincoln offering. That’s where the Lincoln design and management connections ended and it became only a supplier of the drivetrain for the X-1500.

In the beginning, the Organizational Chart consisted of four people, with William Clay Ford as Executive Vice President. WCF went out and recruited the best and brightest from Ford and its competitors. Answering the call were top draftsmen, clay and fiberglass modelers, designers, and even the famous Gordon Buehrig, of Auburn Boattail Speedster fame. WCF is often given credit for the design of the Mark II, but he was actually hired as body engineer after the design had already been etched in stone; his job was to make the design buildable. Ford also contributed his resin model-building skills, essential to the design process.

Some of the first efforts were not very pretty; they were widely panned with HFII offering an expletive-filled assessment.

Instead of letting the design team go back to the drawing board, Ford opened up a design competition to Ford and independent design teams. They were all given a set of design parameters, even down to the size of the images and the colors they used for the renderings. A judging display was constructed so observers would not know which designs belonged to which team.

In the photo below, the top row is the Special Products Division offering. It was decided that the proposed iconic trunk hump be deleted. The team won the competition on its own merits, but the reaction to the faux spare tire on the other contributors’ offerings was so positive the feature was added back into the final design.

Once the design was approved, the team had to find a way to build it—hence Gordon Buehrig being hired as head of the engineering department. Staff had swelled to just under 250 people. William Clay Ford recruited Elmer Rohn away from Chevrolet, where he was working on seats for the Corvette, and put him in charge of the interior of the new car. Those responsibilities included the dashboard and HVAC system. Rohn designed an automatic temperature control for the upcoming Continental Mark III and later patented it.

He started at the beginning of the Mark II project, writing both in official Progress Reports and his own personal diary. Most of the photos used in this story were Ford in-house photographs that he requested to build a 300-photo album, which Hagerty was given permission to use for educational purposes.

Below is Gordon Buehrig describing his design for the smallest and strongest “A” pillar in the industry. It is so small that one can reach around it and touch glass with your thumb and forefinger. William Clay Ford at the wheel.

The converted gymnasium served many duties. Below is a visual comparison with the final Lincoln offering, also in clay. Thankfully, the Mark II lost the side gills on the production car and added to the trunk jewelry.

The ’40s Lincoln Continental had a small-package V-12 that wasn’t very powerful, but it was as smooth as silk, topping out at 138 horsepower for 1942. There was a desire, from the beginning, to fit a V-12 under the hood of a Mark II, hence the clear space behind the 285-hp 368-cubic-inch V-8. A Lincoln engine and transmission were selected, due to smooth operation and near silent-running at 450 rpm. Since there was no other V-12 available, there would have had to have been an enormous investment for the projected production of only 2500 cars a year.

Ford built the Continental Division a new factory in Allen Park in 1954, just after the Special Products Division became the Continental Division. This is where the confusion about a Lincoln Division connection begins. The Continental Division needed its own symbol, as Lincoln was using an eight-point star. The four-point Continental Star was originally round, raising Mercedes’ ire as it had registered a round four-point star in Europe. Once Continental settled on the rectangular version, the casting shops within Ford could not repeatedly produce the fine casting, so they were made by a gunsight manufacturer at the same cost as an entire grille on a ’57 Ford.

Continental sales were robust, at first. The car was to be a Continental series car, like Bentley and others. There was not supposed to be a model year, so all Mark IIs serial numbers begin with C56. Production started in July 1955. Approximately 300 cars were tagged as “INTRODUCTORY UNITS” to be sent to select Lincoln dealers as static displays, and none were to be sold until the new car pipeline had been filled. The Continentals were on consignment; Beth Fordyce, Sales Manager Doug McClure’s office manager, wrote that not a single dealer would take a $10,000 car into the showroom that had to be paid for but it couldn’t sell.

The Division operated at a loss. Development costs were $21,000,000, meaning each $7500 car that was sold to dealers actually cost $8500 to build. And the division was losing far more than the $1000 per car that was reported at the time. The Division was cancelled in a brutal letter from HFII, on file in WCF’s personal files at the Benson Ford Research Center at the entrance to Greenfield Village.

That fateful day ended the 1956–57 Continental Mark II Retractable hard top and unibody Continental Mark III “Berline” four-door, featuring slab sides and rear-hinged rear doors. Rumor has it the only Mark II Retractable was “liberated” by one of the engineers and stashed behind a false wall in Dearborn for 50 years. To cut losses, that technology was passed to the Ford Division, which amassed production of nearly 50,000 Skyliners over three years. The looming recession and Ford’s foray into public ownership upset the balance sheet.

Here’s where Ford Marketing 101 and the Division symbol comes in. Lincoln was working on a line of cars for ’58 that had differing price points and features. The marketing folks seized the opportunity to add to Lincoln’s perceived luxury by trying to make the public think the Continental Division was building the Lincoln Continental Mark III for 1958—taking the symbol on the building and making the breezeway window a “Continental”-only feature. In actuality, the cars had the same sheet metal and identical drivetrains. They were assembled by the same workers on the same line picking from different trim-parts bins. Customers saw through the ruse, and Lincoln dropped the Continental Division claim for the ’59 Mark IV and ’60 Mark V.

Believers simply ignore that the badge below is on the dash of every single Lincoln Continental Mark III.

The Continental Division actually died in November 1956. It took from May until November to wrap up the Division’s business as the remaining employees were being replaced with Edsel Division employees. Buehrig and Rohn went on to Ford Engineering, and William Clay Ford went back to what he loved: being involved with Ford Styling and The Henry Ford Museum.

Everyone found work at Ford and went on with their lives. Beth Fordyce insists there were no clandestine workers gathered to build Continentals in a Lincoln plant. The Continental Division left no forwarding address.

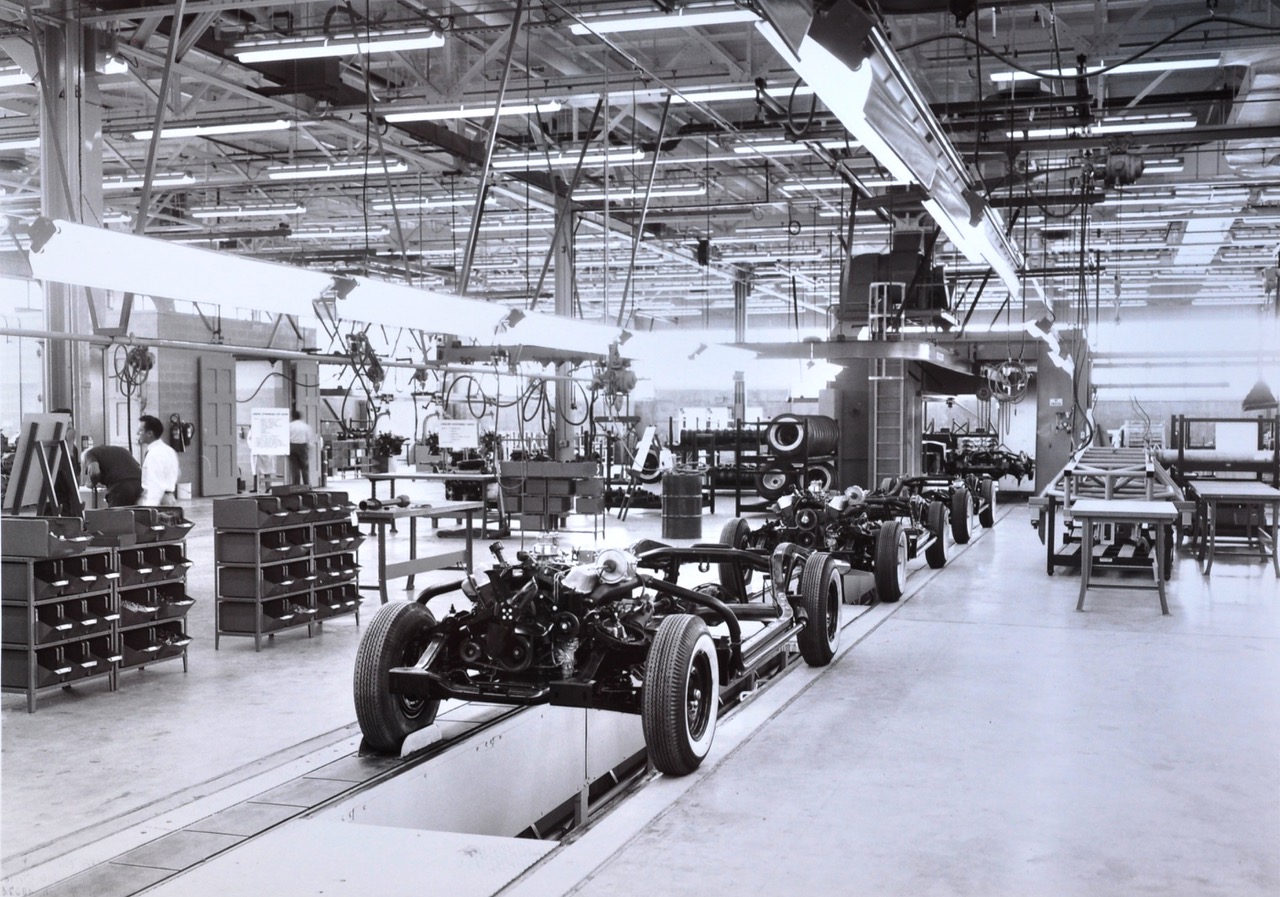

The Continental plant stayed open to build out the balance of the bodies it had under contract from an outside source in Owosso, Michigan. The bodies arrived on rolling pallets that contained all the sheet metal parts in white primer. They required a lot of extra work, and the supplier often didn’t keep up with demand. Each car had to be reworked, but there was no metal fabricating, stamping, or welding facilities. In reality, it was an assembly plant with early “just in time” assembly techniques. The “line” was very short with cars branched off to team-built areas.

Part of Mark II lore is that the engines were built in the plant from hand-picked Lincoln 368 parts. This may be embellishment as is the statements that the engines were dyno-run, disassembled, inspecting each part for wear and reassembled with fresh gaskets seems to not be true as there is nowhere on the floor plan to do that work. The easily identifiable Continental engines were painted gold with black accessories. The “Engine Dress-up” area is where ancillary fuel and power-steering pumps were added as the engine was mated to the automatic transmission. The exhaust headers and valve covers are unique to the Continental. Serial numbers began at 1001, but the engines were stamped by the distributor with a different number, accounting for engines used in prototypes and mules. They were painted over, so they’re often hidden.

Continental became a Lincoln supplier when the Continental Division sold its only running prototype chassis to Lincoln—for an enormous sum of $17,000—for the 1955 Lincoln Futura. Since the whole build cost Ford $250,000, however, that was just a drop in the bucket. Many have suggested that when the car was transformed into the Batman TV car it handled poorly so the customizer swapped the chassis for a later Ford chassis. However, the most current photos of the underside reveal it is indeed sitting on its original Mark II chassis.

The Continental Mark III was fully developed at the time of the cancellation of the Continental program. Note the door handles (below).

Below is the designer’s in-house comparison of the Mark II, Mark III, and the Lincoln offering, just to show that they are distinctly different cars.

Below is the resin model that was built under Buehrig’s supervision and was presented to Ford’s Board of Directors. They were awestruck at the operation, and it never broke in the face of dozens of demonstrations. It was a mechanical masterpiece using linear actuators and cables.

The Mark II is often described as a “hand-built” car, but weren’t they all? Having restored Mark IIs I find that they are no different than any other Ford product of the period. Surely, there are more screws, nuts, and bolts, and they were likely better engineered, but they were essentially the same cars put together by the same workers. Like any other Ford plant, jobs were based on seniority, not necessarily skill level. From the photos (like the one below), the workers were mostly older men.

Below is the entire assembly line. In the rear you see a room for chassis build up after the frame is painted. The engine and transmission come by overhead trolley from the engine dress-up area in the far left corner. They are transported into the dyno room with the doors (to the left); tested engines are rolled to the chassis overhead and fitted to the rolling chassis. Shown are the first four production cars ready to be mated with bodies, but not before the rig to the right is lowered onto each frame, where washers are added to body mounts to insure that the body will sit flat on the chassis.

William Clay Ford (below) was nearly 30 when the Continental Division moved into its new offices in Allen Park. Note the photo of his father and grandfather on his desk. Icons, to be sure.